The first time I experienced the effects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was when my patient dissociated during a treatment session and relived the rape that had occurred when she was ten years old. It was devastating. I didn’t know what to do. She was unresponsive to my intervention. Her eyes didn’t see me, alternating between wide-eyed, horrified panic and clenched-closed, lip biting excruciating pain. It was my late night and I was alone in the clinic. I sat helplessly next to my sweet patient hoping and praying that her torture would end quickly. When she finally stopped writhing, she slept. Deep and hard. Finally she woke up disoriented and scared. She grabbed her things and left. For me, this experience was my initiation into the world of trauma.

Approximately 5-6 % of men and 10-12% of women will suffer from PTSD at some point in their lives. Researchers believe that 10% of people exposed to trauma will go on to develop PTSD. The expression of PTSD symptoms can present differently in men and women. Men may have more externalizing disorders progressing along a scale that includes vigilance, resistance, defiance, aggression and homicidal thoughts. Women tend to present with internalizing disorders such as depression, anxiety, exaggerated startle responses, dissociation, and suicidal thoughts. The research is clear that both men and women with PTSD display changes in brain function. The mid brain (amygdala, basal ganglia and hippocampus) tends to be overactive in sounding alarm signals while the prefrontal cortex fails to turn off the mid brain when a threat is no longer present. Since the prefrontal cortex is not always functioning correctly, traditional talk therapy may not be as effective for treating PTSD. Instead, say many researchers, breath and movement exercises may help regulate brain functioning. Yoga, Tai Chi, and meditation have been shown to have a positive impact on down regulating the mid brain and improving cerebral output. As pelvic floor therapists we deal with trauma on a daily basis, whether we know it or not. Although we are not trained in psychology, understanding PTSD and equipping ourselves with tools to support our patients is imperative for both our patients and ourselves.

Approximately 5-6 % of men and 10-12% of women will suffer from PTSD at some point in their lives. Researchers believe that 10% of people exposed to trauma will go on to develop PTSD. The expression of PTSD symptoms can present differently in men and women. Men may have more externalizing disorders progressing along a scale that includes vigilance, resistance, defiance, aggression and homicidal thoughts. Women tend to present with internalizing disorders such as depression, anxiety, exaggerated startle responses, dissociation, and suicidal thoughts. The research is clear that both men and women with PTSD display changes in brain function. The mid brain (amygdala, basal ganglia and hippocampus) tends to be overactive in sounding alarm signals while the prefrontal cortex fails to turn off the mid brain when a threat is no longer present. Since the prefrontal cortex is not always functioning correctly, traditional talk therapy may not be as effective for treating PTSD. Instead, say many researchers, breath and movement exercises may help regulate brain functioning. Yoga, Tai Chi, and meditation have been shown to have a positive impact on down regulating the mid brain and improving cerebral output. As pelvic floor therapists we deal with trauma on a daily basis, whether we know it or not. Although we are not trained in psychology, understanding PTSD and equipping ourselves with tools to support our patients is imperative for both our patients and ourselves.

You might be wondering what happened after that frightful night in the clinic? My patient was determined to get better. She had a non-relaxing pelvic floor. She was a teacher and was plagued by urinary distress. She either had terrible urgency or would go for hours and not be able to empty her bladder. So we met with her therapist to learn strategies to help us to be able to work together without triggering dissociation. It was a slow road, but the three of us working together helped my patient not only reach her goals but to be able to be skillful enough to maintain her gains using a dilator for self-treatment.

If you would like to learn more about PTSD, meditation, yoga, chronic pain, psychologically informed practice and self-care for patients and providers please join Nari Clemons and I in Tampa in January as we present a new offering for Herman and Wallace, “Holistic Intervention and Meditation.” We would love to see you there.

Bremner, J. D. (2006). Traumatic stress: effects on the brain. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 8(4), 445-461.

Kerr, C. E., Jones, S. R., Wan, Q., Pritchett, D. L., Wasserman, R. H., Wexler, A., ... & Littenberg, R. (2011). Effects of mindfulness meditation training on anticipatory alpha modulation in primary somatosensory cortex. Brain research bulletin, 85(3), 96-103.

Morasco, B. J., Lovejoy, T. I., Lu, M., Turk, D. C., Lewis, L., & Dobscha, S. K. (2013). The relationship between PTSD and chronic pain: mediating role of coping strategies and depression. Pain, 154(4), 609-616.

Olff, M., Langeland, W., & Gersons, B. P. (2005). The psychobiology of PTSD: coping with trauma. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30(10), 974-982.

The Role Of Yoga In Healing Trauma

Examples of pranayama

Ujjayi

Letting Go Breath

Integrating into the clinic

1) Iyengar BKS. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Schocken; 1995.

2) Sapsford RR, Richardson CA, Maher CF, Hodges PW. Pelvic floor muscle activity in different sitting postures in continent and incontinent women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(9):1741-1747.15.

3) Julie Wiebe, Physical Therapist | Educator, Advocate, Clinician. 2015; http://www.juliewiebept.

4) Talasz H, Kremser C, Kofler M, Kalchschmid E, Lechleitner M, Rudisch A. Phase-locked parallel movement of diaphragm and pelvic floor during breathing and coughing-a dynamic MRI investigation in healthy females. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(1):61-68.

5) Sapsford R. Rehabilitation of pelvic floor muscles utilizing trunk stabilization. Man Ther. 2004;9(1):3-12.

6) Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle: An integration of clinical expertise and research, 4e. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

7) Massery M. THE LINDA CRANE MEMORIAL LECTURE: The Patient Puzzle: Piecing it Together. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2009;20(2):19-27.

8) Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle: An integration of clinical expertise and research, 4e. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

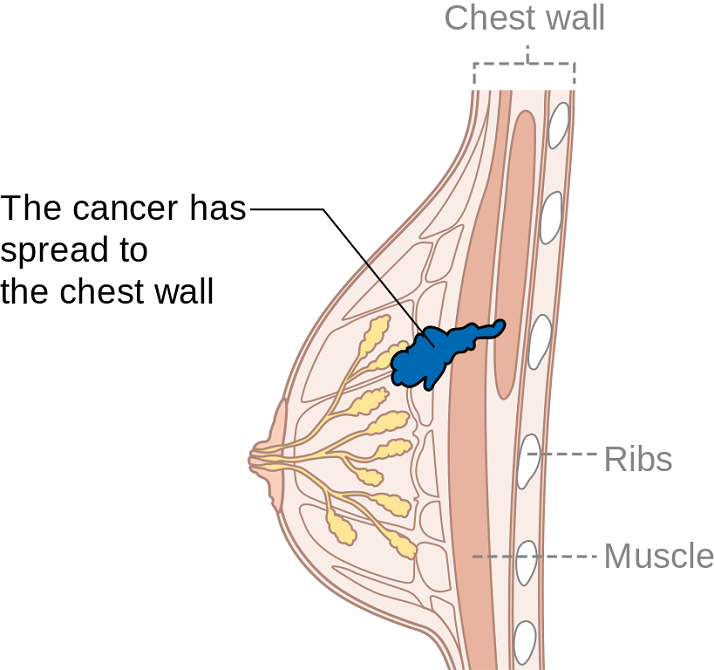

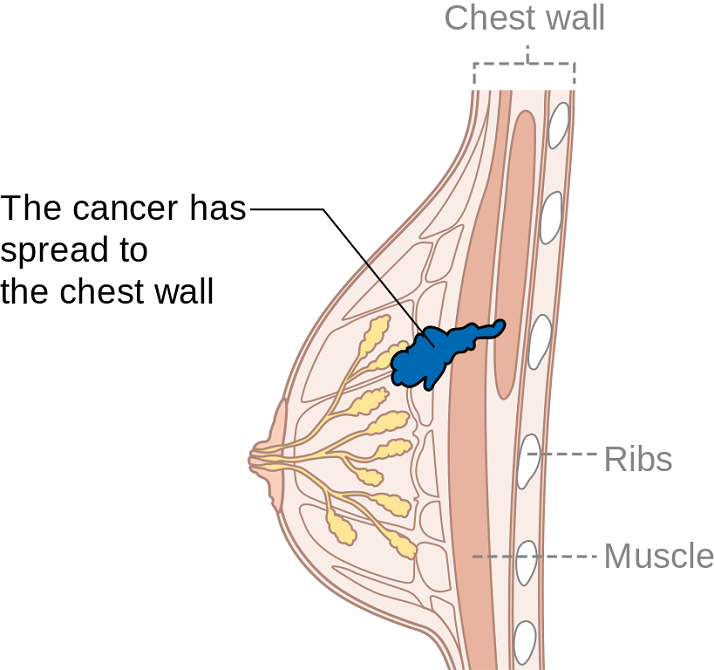

Summer can make women cringe at the thought of baring most of their bodies yet finding just the right coverage for their breasts. Some scrounge for padded tops to pump up their actual A cup. Some seek the greatest amount of coverage to support every ounce of skin. And still others search for flattering tops to accentuate cleavage and minimize tan lines. Just like one swimsuit does not fit every woman, only one aspect of post-breast cancer rehab is not generally sufficient. A combination of exercise, mindfulness, and myofascial release may need to be implemented for optimal recovery.

Ibrahim et al., (2017) produced a pilot randomized controlled trial considering the effects of specific exercise on upper limb function and ability to return to work after radiotherapy for breast oncology. The study involved 59 young women divided into an exercise group or a control group that received standard care. The Disability of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH), the Metabolic Equivalent of Task-hours per week (MET-hours/week), and a post hoc questionnaire on return to work were all used and recorded over 6 time periods after the 12-week post-radiation targeted exercise program. Women who had a total mastectomy still had upper limb dysfunction, but no there was no statistically significant difference in DASH scores between groups. Both groups at 18 months had returned to their pre-illness activity levels, and 86% returned to work (at just 8.5 fewer hours/week). The authors concluded exercise alone does not change the long-term outcome of upper limb function post-radiation.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for persistent pain in women after treatment for primary breast cancer was explored by Johannsen et al., in two 2017 articles, one concerned with clinical and psychological mediators and the other focused on cost-effectiveness. Each study included 129 women with persistent pain from breast cancer, placed in a MBCT group or a wait-list control group. The first study showed attachment avoidance was a statistically significant moderator, with subjects who had a higher attachment avoidance having lower pain intensity after MBCT. In the subjects undergoing radiotherapy, MBCT had a smaller effect on pain than those not having radiotherapy. The authors’ next study focused on the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) on pain intensity. Baseline and 6 months post-treatment data on healthcare utilization and pain medication were analyzed from national registries. The average total cost of the MBCT group was 730 euros less than the control group, and more women in the MBCT group had a MCID in pain than those in the control group.

DeGroef et al., (2017) performed a randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of myofascial techniques for breast cancer survivors who experienced upper limb dysfunctions. Fifty women post-unilateral breast cancer received either 12 sessions of standard physical therapy with myofascial therapy or 12 sessions of standard physical therapy plus a sham intervention during a 3-month period. After intervention, no significant differences between groups were found for active shoulder range of motion, lymphedema, handheld dynamometer strength, scapular statics and dynamics, shoulder function, or quality of life. The authors concluded shoulder ROM and function in both groups showed positive effects up to 1 year follow-up, but myofascial therapy provided no additional benefit in breast cancer patients.

Treatment for any patient should be individualized, based on deficits found clinically, whether they are physiological, anatomical, or psychological. Having a beach bag overflowing with techniques and tools, each ready to be used when the appropriate time comes, makes for a more competent therapist and a better rehabilitation outcome for patients. There simply is no “one size fits all” in breast oncology rehab.

YOU can be a major contributor to a breast cancer patients medical care team. Learn new skills by attending Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient this September in Boston, MA.

Ibrahim, M, Muanza, T, Smirnow, N, Sateren, W, Fournier, B, Kavan, P, Palumbo, M, Dalfen, R, Dalzell, MA. (2017). Time course of upper limb function and return-to-work post-radiotherapy in young adults with breast cancer: a pilot randomized control trial on effects of targeted exercise program. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: research and practice. http://doi:10.1007/s11764-017-0617-0

Johannsen, M, O'Toole, MS, O'Connor, M, Jensen, AB, Zachariae, R. (2017). Clinical and psychological moderators of the effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on persistent pain in women treated for primary breast cancer - explorative analyses from a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncology. 56(2):321-328. http://doi:10.1080/0284186X.2016.1268713

Johannsen, M, Sørensen, J, O'Connor, M, Jensen, AB, Zachariae, R. (2017). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is cost-effective compared to a wait-list control for persistent pain in women treated for primary breast cancer-Results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. http://doi:10.1002/pon.4450

De Groef,A, Van Kampen, M, Verlvoesem N, Dieltjens, E, Vos, L, De Vrieze, T, Christiaen, MR, Neven, P, Geraerts, I, Devoogdt, N. (2017). Effect of myofascial techniques for treatment of upper limb dysfunctions in breast cancer survivors: randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 25(7):2119-2127. http://doi:10.1007/s00520-017-3616-9

Preterm birth can have deleterious health effects not only for the child, but also for the mother. A child may be born so early that various health systems are not matured, leading to susceptibility and delay in development and growth. Maternal health may also be severely impacted, with conditions such as anxiety and psychological stress. Managing the prevention of a pre-term delivery can be stressful and challenging for a pregnant woman, and authors Ha & McDonald (2016) report that this issue is not well studied. A cross-sectional survey was completed to find out not only what a woman’s preferences and concerns are, but also to find out which recommendations were likely to be followed by the patient. This is important, the authors state, because women who are actively involved in medical decisions are more likely to feel satisfied with their childbirth experience.

The survey was completed by 311 women at a median of 32 weeks gestation. Mean age was 30.9, and the majority of them identified as European/White-Caucasian. Most of them were married or in a common-law relationship and had received some level of post-secondary education. The majority of women who were told they were at increased risk of preterm labor (PTL) preferred close-monitoring rather then PTL prevention. Of interest is that the majority of women reported they would use other sources of information besides their primary provider, with the most reported source being the internet or family and friends. This point begs the question of how high is the quality level or accuracy of the available information on the internet or in the general public? Common available options for prevention included progesterone, cerclage, and pessary use. If a woman is not interested in using recommended prevention strategies, the goal of the rehabilitation clinician should be to, on a constant basis, monitor for symptoms and signs of early labor, and encourage the patient to keep any recommended provider appointments, and stay in close contact with her provider so that close-monitoring may be carried out.

An additional goal for rehabilitation is to provide the mother with strategies that may assist her in managing her anxiety, stress, movement dysfunctions, sleep, and other activities. Prior research has validated the benefits of relaxation training in pre-term labor: a cost-effective, low risk and easily implemented strategy. Training women in such a tool during pregnancy fits well into the rehab provider’s scope, and can be instructed in the clinic (or home!) for home program implementation. Larger newborns, longer gestations, and higher rates of prolonged gestations have been recorded when using relaxation training training for pre-term labor.Janke et al., 1999) Chuang et al. (2012) have documented fewer admissions to neonatal intensive care unit, decreased rates of extreme pre-term birth, and shorter stays in hospital with use of relaxation training. Meditation, mindfulness, deep breathing, visualization, and movement within recommend medical limits may all be valuable tools that make up a part of a patient’s rehabilitation experience. In an article describing how prenatal meditation influences infant behaviors, yoga, singing, and massage therapy are all cited methods for improving maternal and/or fetal health.Chan, 2014

The Herman & Wallace Institute offers a three part series on pregnancy and postpartum. Get started by attending either Care of the Pregnant Patient or Care of the Postpartum Patient. You may also be interested in any of the Mindfulness & Meditation courses, including Holistic Interventions and Meditation, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment, and Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals.

Chan, K. P. (2014). Prenatal meditation influences infant behaviors. Infant Behavior and Development, 37(4), 556-561.

Chuang, L.-L., Lin, L.-C., Cheng, P.-J., Chen, C.-H., Wu, S.-C., & Chang, C.-L. (2012). The effectiveness of a relaxation training program for women with preterm labour on pregnancy outcomes: A controlled clinical trial. [Article]. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49, 257-264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.007

Ha, V., & McDonald, S. D. (2017). Pregnant women’s preferences for and concerns about preterm birth prevention: a cross-sectional survey. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 17(1), 49.

Janke, J. (1999). The effect of relaxation therapy on preterm labor outcomes. Journal Of Obstetric, Gynecologic, And Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN / NAACOG, 28(3), 255-263.

Have you ever tried to teach a patient how to isolate their transversus abdominis (TA) contraction or a pelvic floor muscle (PFM) contraction and the patient had difficulty or you weren’t sure how well they were isolating it? Did you ever wish you had the ability to use real-time ultrasound (US) to confirm which abdominal layers they were isolating or use it for visual feedback to assist in your patient’s learning? Could it be helpful to be able to use real-time US to identify if they were isolating the pelvic floor muscles and give your patient visual feedback? Of course!

Real- time US has been used as an assessment and teaching tool to directly visualize abdominal and PFMs. PFM function can be assessed by observing movement at the bladder base and bladder neck. Various studies have used US on women with and without urinary incontinence (UI). These studies usually use transabdominal (TAUS) and transperineal (TPUS) ultrasound to measure if PFM isometrics or exercises are performed correctly or incorrectly, or how the muscles are functioning.

A 2015 study in the International Urogynecology Journal utilized TAUS to identify the ability to perform a correct elevating PFM contraction and assess bladder base movement during an abdominal curl up exercise. Abdominal curl ups are cited to increase intra-abdominal pressure. Activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure have been cited to provoke stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Abdominal curl ups are often completed in group exercise classes and have been found to provoke SUI in up to 16% of women.

Use of PFM exercises and of “the knack” (performing an isometric pelvic contraction before an exertional activity where intra-abdominal pressure increases, such as before lifting or coughing) has been shown to help manage stress urinary incontinence.

The theory is that elevation of the PFMs during activities that increase intraabdominal pressure (like a curl up) assist in urethral closure and counter act the downward movement, therefore stabilizing the urethra and bladder neck. When using TAUS, while performing a correct PFM contraction, one might expect to see an elevating PFM contraction. In the study, TAUS was used on 90 women participating in a variety of group exercise classes. The participants completed a survey and then three attempts of an abdominal curl up exercise in hooklying. During the curl ups, bladder base displacement was measured to determine correct or incorrect activation patterns. It was found that 25% of the women were unable to demonstrate an elevating PFM contraction, and all women displayed bladder base depression on the abdominal curl exercise. It was also found that parous women displayed more bladder base depression than nulliparous women, and overall 60% of the participants reported SUI. Lastly, this study found there was no association between SUI and the inability to perform an elevating PFM contraction or the amount of bladder base depression.

What interesting information. Using real time US in the clinic could help us identify if our patients were completing “the knack” correctly with specific activities. This study is a great example of how we can use real time US to help collect evidence to provide us with more information that can help us answer our own questions, patient questions, and improve our instructional methods to patients when teaching core or PFM exercises.

1) Barton, A., Serrao, C., Thompson, J., & Briffa, K. (2015). Transabdominal ultrasound to assess pelvic floor muscle performance during abdominal curl in exercising women. International urogynecology journal, 26(12), 1789-1795.

“To me it felt like I was just sitting on bed rest, waiting to have a seizure, you know, waiting to start circling the drain.” “Every time I went to the doctor I had this…anxiety attack.” These are the words of pregnant women diagnosed with preeclampsia and on bed rest. Other phrases reported by the authors who interviewed women on bedrest included “…an impending doom…”, “…meltdown…”, “nervous wreck.” A few of the major themes that emerged in the interviews was that of negative thoughts and feelings, family stressors, and not being heard. And while using the term “crazy” is not truly appropriate, women who are forced to abruptly stop interacting and participating in their typical life activities must be regarded as being very high risk for more than just physical issues. Kehler et al., 2016

In an ideal situation, bed rest during pregnancy is prescribed to help keep the mother and fetus healthy. Unfortunately, bed rest in itself is associated with potentially negative consequences in physical and mental health, and providers are not always up-to-date on changing recommendations for bedrest. Perhaps the cautious attitude of providers towards minimizing risk guides some choices. In addition, many women describe frustration about lack of clear guidelines, difficulty managing their stressful feelings, and varying degrees of support from medical providers.

In an ideal situation, bed rest during pregnancy is prescribed to help keep the mother and fetus healthy. Unfortunately, bed rest in itself is associated with potentially negative consequences in physical and mental health, and providers are not always up-to-date on changing recommendations for bedrest. Perhaps the cautious attitude of providers towards minimizing risk guides some choices. In addition, many women describe frustration about lack of clear guidelines, difficulty managing their stressful feelings, and varying degrees of support from medical providers.

During pregnancy-related bed rest, research has described how the entire family is affected. Physically, the mother may have changes in her circadian rhythms, increased anxiety, depression, and hostility. The rest of the family can also experience and demonstrate stress. Other children may act out, partners may be more stressed and worried, and financial strain may be a concern. Bigelow & Stone, 2011 Although we as rehab professionals may not have solutions for every issue, we may be able to facilitate accessing resources and at a minimum hear what a woman is dealing with during this stressful time. Many women, even when on bedrest, are allowed to attend medical appointments such as physical therapy, and should be provided with appropriate physical and mental activities to help minimize muscle atrophy and stress. Home health or hospital-based providers are also in a perfect position to educate providers on the value of referrals while the patient is at home or in the hospital.

We should keep these issues in mind during pregnancy as well as in the postpartum period. Maloni & Park (2005) measured postpartum symptoms in women who were on bedrest during pregnancy, and at 6 weeks postpartum, 40% of the 106 women (high-risk, singleton) complained of mood changes, difficulty concentrating, and other physical issues. Women who had a c-section had worsened symptoms, and the length of time on bed rest was highly correlated with the number of symptoms.

Bed rest affects a woman’s cognition, creates fear, a sense of lack of control, powerlessness, and even anger. “Because of this, Rodrigues and colleagues (Rodrigues et al., 2016) suggest that “…mental disorders should be routinely investigated during high-risk pregnancy, whenever possible with the use of specific instruments so that they can be detected early and so that interventions can be made in due time.” If you are interested in discussing this issue and many others, check out the Institute’s continuing education choices in peripartum health. The next Care of the Postpartum Patient course is taking place on September 16-17, 2017 in Nashville, TN.

Bigelow, C., & Stone, J. (2011). Bed rest in pregnancy. The Mount Sinai Journal Of Medicine, New York, 78(2), 291-302. doi: 10.1002/msj.20243

Kehler, S., Ashford, K., Cho, M., & Dekker, R. L. (2016). Experience of Preeclampsia and Bed Rest: Mental Health Implications. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(9), 674-681.

Maloni, J. A., & Park, S. (2005). Postpartum Symptoms After Antepartum Bed Rest. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 34(2).

Meher, S., Abalos, E., & Carroli, G. (2005). Bed rest with or without hospitalisation for hypertension during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4.

Rodrigues, P. B., Zambaldi, C. F., Cantilino, A., & Sougey, E. B. (2016). Special features of high-risk pregnancies as factors in development of mental distress: a review. Trends in psychiatry and psychotherapy, 38(3), 136-140.

Everyone experiences constipation, sometime! Maybe it was on vacation and you felt bloated and miserable; or when you were busy at work and had to rush to complete a task. In any event, you felt ‘awful’. Maybe you couldn’t zip your favorite jeans due to abdominal bloating, maybe you experienced lower abdominal discomfort or experienced a painful ‘movement’ once you went. There are many people who experience these symptoms and more on a daily basis. When someone finally gets the courage to see a specialist about this problem, they might be diagnosed with ‘pelvic floor dyssynergia’ or ‘muscle incoordination’.

Pelvic muscle dyssysnergia (incoordination) refers to the action that occurs in the pelvic floor musculature at the time of defecation. It can become a withholding pattern and in the case of vacation or a change in your work schedule, it can simply be tensing the muscle to avoid the bowel movement (due to inconvenience) rather than heeding the ‘call’. Over time, if this behavior is repeated, it becomes muscle memory; instead of relaxing the pelvic muscle to defecate, the patient tenses the muscle; thus the term dyssynergia or incoordination. The function of the pelvic floor for bowel function is to provide closure of the anal canal to maintain continence. The muscle should signal the rectum and the colon when to defecate and should provide opening of the anal canal by total relaxation to allow for complete and effortless elimination. A dyssynergic pattern shuts the opening of the canal by tensing the muscle to prevent elimination. Thus an incoordination.

The research by Heymen, Scarlett, Ringman, Drossman et al entitled “Randomized, Controlled Trial Shows Biofeedback to Be Superior to Alternative Treatments for Patients with Pelvic Floor Dyssynergia-Type Constipation” supports the value of biofeedback in the treatment of this withholding pattern associated with stool elimination. This study supports the benefit of biofeedback treatments using internal sensors to provide the feedback displayed on a computer screen for visualization. This study goes on to say, “We also have shown that the machines are necessary—instrumented biofeedback is an essential element of successful training; however, there is a shortage of practitioners who are trained to provide this form of biofeedback, and there are few clinics where biofeedback instruments are available and where this form of biofeedback can be obtained”.

Biofeedback provides visual and auditory feedback of muscle tension. It is a non-invasive technique that allows patients to adjust muscle function, strength, and behaviors to improve pelvic floor function. The small electrical signal (EMG) provides information about an unconscious process and is presented visually on a computer screen, giving the patient immediate knowledge of muscle function, enabling the patient to learn how to alter the physiological process through verbal and visual cues. This mechanism allows the patient to assess muscle resting tone, creating an environment that teaches how to downtrain a tense pelvic floor while providing the means to teach co-ordination of muscle function.

In short, biofeedback treatment/training using the proper instrumentation provides the precise information necessary to change behaviors associated with tensing the pelvic floor for defecation instead of the proper relaxation of the pelvic floor for release of stool from the anal canal.

The Herman Wallace Course on Biofeedback Training for Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction provides the clinician with the proper treatment technique to use in the clinic to rehabilitate patients with pelvic floor muscle dyssynergia. Learning the proper use of biofeedback equipment and understanding the components to treating these challenging patients successfully is an essential component to this course. The clinician will learn numerous ways to teach this challenging patient population how to make this muscle function as intended, providing the patient with successful strategies for improved patient outcomes.

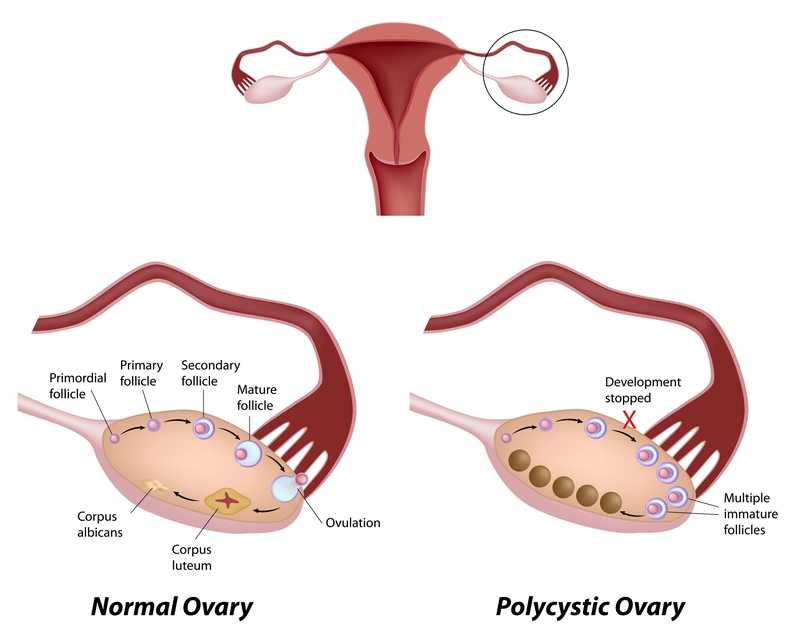

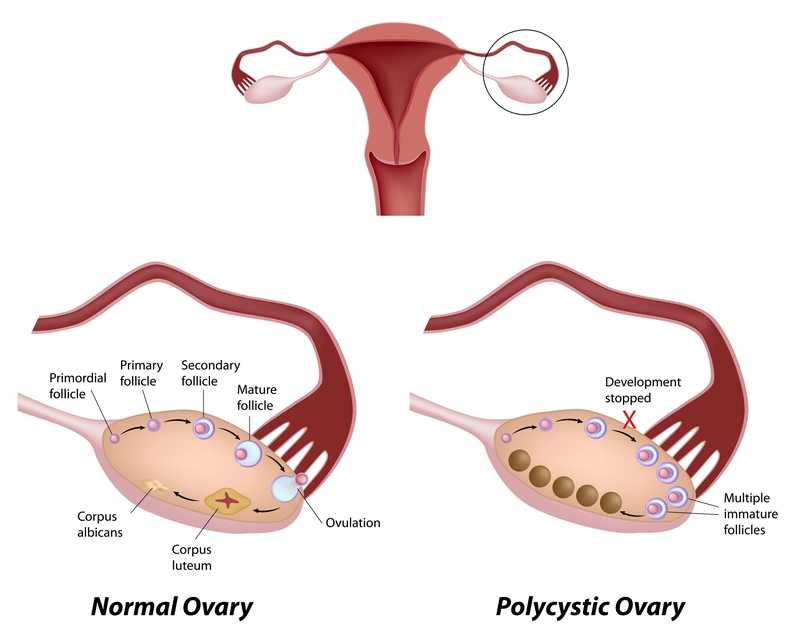

Polycystic ovarian disease (PCOS), also known as Stein-Leventhal syndrome, is an endocrine system disorder that affects women of reproductive age. The disease is associated with some major adverse health issues including infertility, diabetes, metabolic syndrome (a cluster of conditions that increase risk for heart disease, stroke and diabetes), cardiovascular issues and endometrial carcinoma. Because, according to Okamura et al., those with PCOS share risk factors for endometrial cancer and atypical endometrial hyperplasia, early detection and treatment are critical for optimal health outcomes. Some of the primary shared risk factors include obesity, not bearing any children (nulliparity), infertility, hypertension, diabetes, chronic anovulation, and unopposed estrogen supplementation.

One study (Malcolm2017) that addressed reproductive health comparisons among young women with and without PCOS found that although women diagnosed with PCOS had significant concerns about their reproductive health, they were found to be as sexually active as young women without PCOS. Unfortunately, women with PCOS were more likely to have pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which could increase the risk of infertility. In this study, the importance of counseling in safe sex practices such as condom use and sexually transmitted infection screening was highlighted.

As weight loss in women diagnosed with PCOS has been shown to improve blood sugar levels, exercise and healthy weight management strategies can also be keystones of care. Vasheghani-Farahani et al report on a home-based exercise program with positive outcomes in health for women with PCOS. The women in this study were ages 15-40, with 16 patients in the exercise group and 14 in the control group. Blood pressure, waist to hip ratio, BMI, blood tests for insulin factors, sex hormones, and markers of inflammation made up outcomes measures at baseline and again at 12 weeks following intervention. The active group completed aerobic and strengthening exercises and were found to have an improved waist to hip ratio as well as reductions in cardiovascular risk profiles.

The exercise instructed as home program is as follows: 30 minute walk at least 5 days per week at medium intensity (64%-76% max heart rate), strengthening exercises of biceps curl, wall push up, chair push up, single arm row, seated lower leg lift, seated straight leg lift, stair step and chair squat 10 times each. The participants were instructed to increase the exercise bouts per day from 1 to 3 by the end of the study. Participants were guided through the exercises at the beginning of the study, and exercise logs as well as phone calls were used to track progress, answer questions.

This study is an encouraging example of simple yet effective strategies to guide women diagnosed with PCOS. Although there are other equally valuable aspects of care that a pelvic health therapist can be involved in for women managing this challenging disease, the research presented reminds us that basic information on healthy sexual practices and provider follow-up, strengthening and aerobic exercise can have meaningful impact on quality of life. If you are interested in learning more about PCOS and other endocrine conditions, and ways to help manage pelvic pain, adhesions, and other symptoms, join us in Pelvic Floor Series Capstone: Advanced Topics in Pelvic Rehab, available twice more in 2017.

Malcolm, S., Tuchman, L., Cheng, Y. I., Wang, J., & Gomez-Lobo, V. (2017). Differences in Reproductive Health Issues in Adolescent Females With Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Compared to Controls. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 30(2), 330-331.

Okamura, Y., Saito, F., Takaishi, K., Motohara, T., Honda, R., Ohba, T., & Katabuchi, H. (2017). Polycystic ovary syndrome: early diagnosis and intervention are necessary for fertility preservation in young women with endometrial cancer under 35 years of age. Reproductive Medicine and Biology, 16(1), 67-71.

Vasheghani-Farahani, F., Khosravi, S., Yekta, A. H. A., Rostami, M., & Mansournia, M. A. (2017). The Effect of Home based Exercise on Treatment of Women with Poly Cystic Ovary Syndrome; a single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Novelty in Biomedicine, 5(1), 8-15.

At a hair salon, I once saw a plaque that declared, “I’m a beautician, not a magician.” This crossed my mind while reading research on radical prostatectomy, as knowing the baseline penile function of men before surgery seemed challenging. Restoring something that may have been subpar prior to surgery can be a daunting task, and it can cause discrepancies in results of clinical trials. Despite this, two recent studies reviewed the current and future penile rehabilitation approaches post-radical prostatectomy.

Bratu et al.2017 published a review referring to post-radical prostatectomy (RP) erectile dysfunction (ED) as a challenge for patients as well as physicians. They emphasized the use of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) Questionnaire to establish a man’s baseline erectile function, which can be affected by factors such as age, diabetes, alcohol use, smoking habits, heart and kidney diseases, and neurological disorders. The higher the IIEF score preoperatively, the higher the probability of recovering erectile function post-surgery. The experience of the surgeon and the technique used were also factors involved in ED. Radical prostatectomy is a trauma to the pelvis that negatively affects oxygenation of the corpora cavernosum, resulting in apoptosis and fibrotic changes in the tissue, leading to ED. Minimally invasive surgery allows a significantly lower rate of post-RP ED with robot assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) versus open surgery. The cavernous neurovascular bundles get hypoxic and ischemic regardless of the technique used; therefore, the authors emphasized early post-op penile rehabilitation to prevent fibrosis of smooth muscle and to improve cavernous oxygenation for the potential return of satisfactory sexual function within 12-24 months.

Clavell-Hernandez and Wang2017 [and Bratu et al., (2017)] reported on various aspects of penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy. The treatment with the most research to support its efficacy and safety was oral phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors (PDE5Is), which help relax smooth muscle and promote erection on a cellular level. Sildenafil, vardenafil, avanafil, and tadalafil have been studied, either used on demand or nightly. Tadalafil had the longer half-life and was considered to have the greatest efficacy. Nightly versus on-demand for any PDE5I was variable in its results. Intracavernosal injection (ICI) and intraurethral therapy using alprostadil for vasodilation improved erectile function, but it caused urethral burning and penile pain. Vacuum erection devices (VED) promoted penile erection via negative pressure around the penis, bringing blood into the corpus cavernosum. There was no need for intact corporal nerve or nitric oxide pathways for proper function, and it allowed for multiple erections in a day. Intracavernous stem cell injections provided a promising approach for ED, and they may be combined with PDE5Is or low-energy shockwave therapy. Ultimately, the authors concluded early penile rehabilitation should involve a combination of available therapies.

Restoring vascularity to healing tissue is a primary goal in rehabilitation, and the sooner the better. Disruption of cavernous nerves and penile tissue post-RP demands rehabilitation, and some methods have more supporting clinical evidence than others. Newer approaches require more exposure and clinical trials for efficacy and long term outcomes. Clinicians should pay attention to updated research and consider taking continuing education courses such as Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation or Oncology and the Male Pelvic Floor.

Bratu, O., Oprea, I., Marcu, D., Spinu, D., Niculae, A., Geavlete, B., & Mischianu, D. (2017). Erectile dysfunction post-radical prostatectomy – a challenge for both patient and physician. Journal of Medicine and Life, 10(1), 13–18.

Clavell-Hernández, J., & Wang, R. (2017). The controversy surrounding penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy. Translational Andrology and Urology, 6(1), 2–11. http://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2016.08.14

Speaking with a runner friend the other day, I mentioned I was writing a blog on yoga for pelvic pain. She had the same reaction many runners do, stating she has doesn’t care for yoga, she never feels like she is tight, and she would hate being in one position for so long. Ironically, neither of us has taken a yoga class, so any preconceived ideas about it are null and void. I told her yoga is being researched for beneficial health effects, and one day we just might find ourselves in a class together!

Saxena et al.2017 published a study on the effects of yoga on pain and quality of life in women with chronic pelvic pain. The randomized case controlled study involved 60 female patients, ages 18-45, who presented with chronic pelvic pain. They were randomly divided into two groups of 30 women. Group I received 8 weeks of treatment only with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDS). Group II received 1 hour, 5 days per week, for 8 weeks of yoga therapy (asanas, pranayama, and relaxation) in addition to NSAIDS (as needed). Table 1 in the article outlines the exact protocol of yoga in which Group II participated. The subjects were assessed pre- and post-treatment with pain scores via visual analog scale score and quality of life with the World Health Organization quality of life-BREF questionnaire. In the final analysis, Group II showed a statistically significant positive difference pre and post treatment as well as in comparison to Group I in both categories. The authors concluded yoga to be an effective adjunct therapy for patients with chronic pelvic pain and an effective option over NSAIDS for pain.

Saxena et al.2017 published a study on the effects of yoga on pain and quality of life in women with chronic pelvic pain. The randomized case controlled study involved 60 female patients, ages 18-45, who presented with chronic pelvic pain. They were randomly divided into two groups of 30 women. Group I received 8 weeks of treatment only with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDS). Group II received 1 hour, 5 days per week, for 8 weeks of yoga therapy (asanas, pranayama, and relaxation) in addition to NSAIDS (as needed). Table 1 in the article outlines the exact protocol of yoga in which Group II participated. The subjects were assessed pre- and post-treatment with pain scores via visual analog scale score and quality of life with the World Health Organization quality of life-BREF questionnaire. In the final analysis, Group II showed a statistically significant positive difference pre and post treatment as well as in comparison to Group I in both categories. The authors concluded yoga to be an effective adjunct therapy for patients with chronic pelvic pain and an effective option over NSAIDS for pain.

In the Pain Medicine journal, Huang et al.2017 presented a single-arm trial attempting to study the effects of a group-based therapeutic yoga program for women with chronic pelvic pain (CPP), focusing on severity of pain, sexual function, and overall well-being. The comprehensive program was created by a group of women’s health researchers, gynecological and obstetrical medical practitioners, yoga consultants, and integrative medicine clinicians. Sixteen women with severe pelvic pain of at least 6 months’ duration were recruited. The group yoga classes focused on lyengar-based techniques, and the subjects participated in group classes twice a week and home practice 1 hour per week for 6 weeks. The Impact of Pelvic Pain (IPP) questionnaire assessed how the participants’ pain affected their daily life activities, emotional well-being, and sexual function. Sexual Health Outcomes in Women Questionairre (SHOW-Q) offered insight to sexual function. Daily logs recorded the women’s self-rated pelvic pain severity. The results showed the average pain severity improved 32% after the 6 weeks, and IPP scores improved for daily living (from 1.8 to 0.9), emotional well-being (from 1.7 to 0.9), and sexual function (from 1.9 to 1.0). The SHOW-Q "pelvic problem interference" scale also improved from 53 to 23. The multidisciplinary panel concluded they found preliminary evidence that teaching yoga to women with CPP is feasible for pain management and improvement of quality of life and sexual function.

Whatever treatment we provide for our patients, we need to consider the individual and their often biased opinions or perceptions. Providing research and educating each patient on the efficacy behind the proposed therapy will likely impact their outcome. The Yoga for Pelvic Pain course can enhance a clinician’s understanding and allow them to better implement a potentially life-changing therapy for their clients.

Saxena, R., Gupta, M., Shankar, N., Jain, S., & Saxena, A. (2017). Effects of yogic intervention on pain scores and quality of life in females with chronic pelvic pain. International Journal of Yoga, 10(1), 9–15. http://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.186155

Huang, AJ, Rowen, TS, Abercrombie, P, Subak, LL, Schembri, M, Plaut, T, & Chao, MT. (2017). Development and Feasibility of a Group-Based Therapeutic Yoga Program for Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain. Pain Medicine. http://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw306