Mia Fine, MS, LMFT, CST joins the Herman & Wallace faculty in 2020 with her new course on Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists! The new course is launching this April 4-5, 2020 in Seattle, WA; Lecture topics include bio-psycho-social-spiritual interviewing skills, maintaining a patient-centered approach to taking a sexual history, and awareness of potential provider biases that could compromise treatment. Labs will take the form of experiential practice with Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual-Sexual Interviewing Skills, case studies and role playing. Check out Mia's interview with The Pelvic Rehab Report, then join her for Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists!

Tell us about yourself, Mia!

Tell us about yourself, Mia!

My name is Mia Fine, MS, LMFT, CST and I’ve been a Licensed Marriage and Family therapist for four years. I am an AASECT Certified Sex Therapist and my private practice is Mia Fine Therapy, PLLC. I see these kinds of patients: folks with Erectile Dysfunction, Pre-mature Ejaculation, Vaginismus, Dyspareunia, Desire Discrepancy, LGBTQ+, Ethical Non-monogamy, Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, Relational Concerns, Improving Communication.

What can you tell us about the new course?

This course will offer a great deal of current and empirically-founded sex therapy and sex education resources for both the provider as well as the patient. This course will add the extensive skills of interviewing for sexual health. It also offers the provider a new awareness and self-knowledge on his/her/their own blind spots and biases.

How will skills learned at this course allow practitioners to see patients differently?

Human beings are hardwired for connection, intimacy, and pleasure. Our society often tells us that there is something wrong with us, or that we are defective, for wanting a healthy sex life and for addressing our human needs/sexual desires. This course will broaden the provider’s scope of competence in working with patients who experience forms of sexual dysfunction and who hope to live their full sexual lives.

What inspired you to create this course?

This course was inspired by the need for providers who work with pelvic floor concerns to be trained in addressing and discussing sexual health with their patients.

What resources were essential in creating your course?

Becoming a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and a Certified Medical Family Therapist requires three years of intensive graduate school. Additionally, a minimum of two years of training to become an AASECT Certified Sex Therapist and hundreds of hours of direct client contact hours, supervision, and consultation. I attend numerous sex therapy trainings and continuing education opportunities on a regular and ongoing basis. I also train incoming sex therapists on current modalities and working with vulnerable client populations.

How do you think these skills will benefit a clinician in their practice?

It is vital that providers working with pelvic floor concerns have the necessary education and training to work with patients on issues of sexual dysfunction. It is also important that providers be aware of their own biases and be introduced to the various sexual health resources available to providers and patients.

What is one important technique taught in your course that everybody should learn?

Role playing sexual health interview questions is an important experience in feeling the discomfort that many providers feel when asking sexual health questions. This offers insight not only into the provider experience but also the patient’s experience of uncomfortability. Role playing this dynamic illustrates the very real experiences that show up in the therapeutic context.

Sexuality is core to most human beings’ identity and daily experiences. When there are concerns relating to our sexual identity, sexual health, and capacity to access our full potential, it affects our quality of life as well as our holistic well-being. Working with folks on issues of sexual health and decreasing sexual dysfunction encourages awareness and encourages healing. Imagining a world where human beings don’t walk around holding shame or traumatic pain is imaging a world of health and happiness.

Pelvic pain is a common diagnosis that we see as pelvic floor therapists. Pelvic pain is pain located in the lower abdomen, but above pubic symphysis, and is associated with various causes; myofascial pain, neuropathies, endometriosis, painful bladder, and irritable bowel syndromes. A common symptom of pelvic pain is deep dyspareunia or pain with deep vaginal penetration. Vulvar pain is different, as it is below pubic symphysis, and has several sub-classifications. These sub-classifications can often be confusing. The National Vulvodynia Association has a free online education that explains the different sub-types very succinctly. This article focuses on provoked vestibulodynia, which is the most commonly studied.

PVD or Provoked Vestibulodynia often has superficial dyspareunia which can negatively affect sexual functioning, which can lead to changes in psychological function and quality of life. Women with PVD often complain of greater pain during and after intercourse, pain catastrophization, and allodynia when compared to women with superficial dyspareunia but without PVD. These symptoms indicate central nervous system upregulation or sensitivity. This study sought to investigate the impact of these symptoms.

PVD or Provoked Vestibulodynia often has superficial dyspareunia which can negatively affect sexual functioning, which can lead to changes in psychological function and quality of life. Women with PVD often complain of greater pain during and after intercourse, pain catastrophization, and allodynia when compared to women with superficial dyspareunia but without PVD. These symptoms indicate central nervous system upregulation or sensitivity. This study sought to investigate the impact of these symptoms.

Pelvic pain encompassed a variety of complaints: “dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, dyschezia, chronic pelvic pain, back pain, or diagnosed or suspected endometriosis”. Participants were excluded if postmenopausal or if self reported never sexually active.

One hundred twenty nine participants were divided into those with pelvic pain and PVD (43), and those with pelvic pain alone (87). For this study PVD was diagnosed as superficial dyspareunia (>4/10) and positive Q-tip test with a fixed pressure of 30g. Those with did not meet this criteria were considered to have pelvic pain alone.

The two groups were compared for superficial and deep sexual discomfort severity, sexual quality of life; fear avoidance, feelings of guilt, frustration, etc, physical examination of trigger points along abdominal wall (positive Carnett test), and numeric pain scale of various painful lumbo-pelvic regions.

Of the 129 participants notable findings in both the two groups include 31% had confirmed endometriosis, 40% suspected of endometriosis, and in the remaining 18% had no confirmed or suspected endometriosis. The authors found that the pelvic pain + PVD group had significantly more superficial dyspareunia (p=<.001) and deep dyspareunia (p=.001) which was rated >7/10 for both. This group was also had greater (3x more likely to have) depression symptoms, greater anxiety, and catastrophizing, and was more likely to have painful bladder syndrome than the pelvic pain alone group. There were no differences between the two groups for irritable bowel syndrome or abdominal wall tenderness.

This research is consistent with other research findings. The authors explore various causes of the findings including; cross- sensitization - where there may be cross talk of nerve signals from viscera to viscera and viscera to muscular structures that converge in the spinal cord. The authors note that the poor relationship between PVD and irritable bowel and PVD and abdominal wall tenderness limit that theory. They explore the psychological symptoms may be a consequence of pelvic pain or it may be that having anxiety/depression may make women more sensitive to developing pelvic pain and PVD. This sounds like a little chicken or egg theory. The authors suggest that those with PVD and pelvic pain may benefit from a more intensive multi-disciplinary approach including; “medical, surgical, psychological, or physical therapy approaches”.

Bao, C., Noga, H, Allaire, C. et al. “Provoked Vestibulodynia in Women with Pelvic Pain” Sex Med 2019; 1-8

Four years ago, I sat with a tiny nugget in my arms and I stared in awe of this beautiful creature. She was perfect, she was amazing, she was… hungry! And I had no idea what to do.

Breastfeeding is at the core of our human experience and it is what defines us as mammals. Have you ever stopped to think about the link between mammal, mammary gland, and mama? And yet, for something so natural, it sure can take a lot of work to figure out.

Breastfeeding is at the core of our human experience and it is what defines us as mammals. Have you ever stopped to think about the link between mammal, mammary gland, and mama? And yet, for something so natural, it sure can take a lot of work to figure out.

In advance of the breastfeeding courses for physical therapists in Phoenix and New Jersey this year, I’ve prepared a list of my favourite myths about breastfeeding. Take a look and tag us on social media if any of them surprised you!

Myth #1: Men can’t breastfeed

We’re starting off with one that seems obvious: surely, men can’t produce milk in sufficient quantities to feed an infant. If they could, then couples around the world would split parenting duties very differently. Right?

Well…

Let’s take a deeper dive into this myth. First, it depends on how you define a man. There are trans men who give birth and then feed their infants. There are also gender nonbinary people who don’t give birth and can still lactate. The permutations of unique situations are plentiful. Some refer to this practice as breastfeeding, while others call it chestfeeding. Ask the individual about their preferred terms, just like you would talk about pronouns. For more information on gender and chestfeeding, check out this article1.

An interesting fact about men and lactation is that domperidone – one of the most common medications in breastfeeding medicine – can contribute to male lactation, even when it is being taken for a different indication2. Domperidone elevates the levels of prolactin, a hormone that signals the lactocytes in the breast to produce milk.

Myth #2: An oversupply of milk is always a good thing

If you’ve looked on postpartum Facebook groups and blogs, you’ve likely seen discussions of undersupply, not having enough milk, and the seemingly uphill battle to make more. There are countless forum posts on switch feeding, power pumping, galactalogues (medications and herbs to increase milk production), etc. Perceived insufficient milk consistently appears among the top reasons for supplementation or breastfeeding cessation3,4,5.

When I was pregnant with my daughter, I made plans to exclusively breastfeed her, pump once a day, and donate the extra milk to a local milk bank. Surely, I thought, the only consequence of making extra milk would be the work involved in making the donations. None of this actually happened but that’s a story for another day.

What I’ve come to learn from working with patients is that in the production of milk, any mismatch of supply and demand can impact a person’s quality of life. Signs of oversupply include6:

- Coughing or gagging during feeds

- Baby is fussy at the breast, possibly crying or arching their back

- Baby is gassy between feeds

- The breasts always feel full

- Recurrent breast inflammation such as blocked ducts and mastitis

- Nipple pain and tissue damage from biting

Fast milk flow can also make the task more difficult for babies with an uncoordinated suck/swallow/breathe pattern. If the mechanics or timing is off, the infant will prioritize airway protection and may appear to go on and off the breast throughout the feed.

Myth #3: For a blocked duct, point the baby’s chin toward the affected area

Have you seen it? There’s an image that makes the rounds on social media and it compares the milk-producing components of breast tissue to a flower. This imagery is beautiful, and it sparks conversation every time I see it. If you can’t picture it, think of the milk ducts as the spokes of a bicycle with lobules at the end of each one. They’re neatly arranged in a perfect circle.

If this is how the ducts are arranged, then the infant’s mandible and tongue will draw milk from the affected area during feeds and that will help to resolve the “blockage.” In reality, though, the ducts do not follow straight paths from lobule to nipple. They wind and weave around each other, branching along the way, and milk that comes out the lateral side of the nipple may have originated in the medial part of the breast7.

If this is how the ducts are arranged, then the infant’s mandible and tongue will draw milk from the affected area during feeds and that will help to resolve the “blockage.” In reality, though, the ducts do not follow straight paths from lobule to nipple. They wind and weave around each other, branching along the way, and milk that comes out the lateral side of the nipple may have originated in the medial part of the breast7.

There’s a second reason why the chin pointing won’t resolve a blocked duct: it turns out that there’s no evidence for the existence of a blockage in the first place. We often picture a blocked duct like a coronary artery, with an obstruction that is preventing the flow of milk (or blood) through the vessel. In reality, the ducts are easily collapsible7 and localized inflammation8 and swelling can compress the ducts, preventing milk flow.

Myth #4: Mastitis means infection

Our last myth is perhaps the most pervasive of the list. Many people – including physicians – think that the difference between mastitis and blocked ducts is that mastitis involves a pathogen or infection. Depending on where you live, it may be common practice to prescribe antibiotics for all cases of mastitis.

According to the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine and the World Health Organization, infection is only one of the causes of the condition8,9. Mastitis is defined as inflammation of the breast, which may be infectious or non-infectious in nature. Non-infectious cases can be attributed to mechanical factors such as distension of the breast alveoli and/or chemical factors like pro-inflammatory cytokines entering the parenchyma8.

What this means is that there are many cases of mastitis that can benefit from someone who can help with inflammation management. To me, that sounds like a physical therapist. We have a role to play not only in the local tissue, but also in the biopsychosocial approach that’s required in addressing a person’s pain.

Learn more aboutevidence-based management principles for breastfeeding conditions at the Herman & Wallace course Breastfeeding Conditions: Mastitis, Nipple Pain, and Maternal Factors in Lactation, taking place this year in Phoenix, AZ this March and Princeton, NJ this August. I look forward to discussing these topics and more!

1. MacDonald, T. (2018). Transgender parents and chest/breastfeeding. Retrieved from https://kellymom.com/bf/got-milk/transgender-parents-chestbreastfeeding/

2. Sanis Health Inc. (2015). Domperidone product monograph [PDF file]. Retrieved fromhttps://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00030125.PDF

3. Li, R., Fein, S. B., Chen, J., & Grummer-Strawn, L. M. (2008). Why mothers stop breastfeeding: mothers’ self-reported reasons for stopping during the first year. Pediatrics, 122(Supp. 2), S69-S76.

4. Gatti, L. (2008). Maternal perceptions of insufficient milk supply in breastfeeding. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 40(4), 355-363.

5. Ahluwalia, I. B., Morrow, B., & Hsia, J. (2005). Why do women stop breastfeeding? Findings from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System. Pediatrics, 116(6), 1408–1412.

6. La Leche League International (n.d.). Oversupply. Retrieved from https://www.llli.org/breastfeeding-info/oversupply

7. Ramsay, D. T., Kent, J. C., Hartmann, R. A., & Hartmann, P. E. (2005). Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. Journal of anatomy, 206(6), 525-534.

8. World Health Organization. (2000). Mastitis: causes and management (No. WHO/FCH/CAH/00.13). World Health Organization.

9. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Protocol Committee. (2008). ABM clinical protocol# 4: mastitis. Breastfeeding Medicine, 3(3), 177-180.

If you work with orthopedic patients, I am sure that you have had a back-pain patient that you have discharged, only for them to return a year later suffering from another episode of pain. We all know that once someone suffers from a back injury, they are more likely to develop a chronic issue. Even patients with insidious back pain and no specific injury often develop chronic issues and can have pain that waxes and wanes after the initial episode.

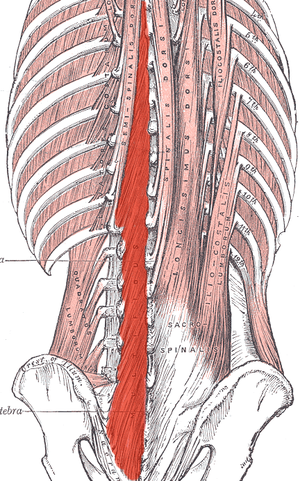

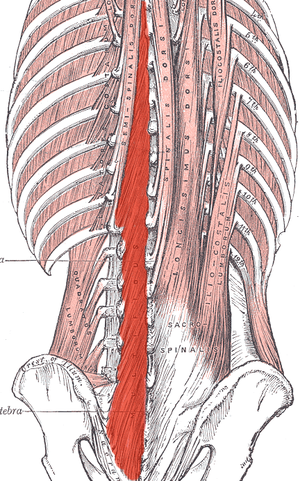

What happens in the body to cause this? Most of us have learned that the pelvic floor, transverse abdominus, and the deep fibers of the lumbar multifidus play an important role in stabilization. With injury, these muscles can become less effective in stabilizing the spine and pelvis. Studies have shown that muscle atrophy in the lumbar multifidus has been shown to occur with injuries and persist after resolution of the pain.1

What happens in the body to cause this? Most of us have learned that the pelvic floor, transverse abdominus, and the deep fibers of the lumbar multifidus play an important role in stabilization. With injury, these muscles can become less effective in stabilizing the spine and pelvis. Studies have shown that muscle atrophy in the lumbar multifidus has been shown to occur with injuries and persist after resolution of the pain.1

I recently did additional research to find out other reasons that cause these local stabilizing muscles to not function optimally. I found that these muscles also can suffer from arthrogenic muscle inhibition after an episode of low back pain.2 Arthogenic inhibition is a deficit in neural activation to a muscle. It is thought to occur due to a change in the discharge of articular sensory receptors due to swelling, inflammation, joint laxity, and damage to afferent nerves.2 EMG studies have shown reduced neural activity in the deeper fibers of the multifidus in patients with back pain.3

Another thing that fascinated me was that cortical changes in the brain also occur with low back pain. Changes in cortical representation of the multifidus and the body’s ability to voluntarily activate the muscle has been noted.4 Motor retraining has been shown to reorganize the motor cortex with regards to the transverse abdominus.5 Also, improvement in brain organization and function occurs after resolution of back pain.6

This is good news for patients! As therapists, we may not be able to do anything with respects to arthogenic inhibition. However, we can work on motor retraining for the core muscles. It has been shown that specific training that targets the multifidus can restore the neural activity to the multifidus and lead to improvement of pain and function.7,8 Training the multifidus can be difficult for therapists to teach. However, studies have found that ultrasound guided biofeedback is helpful for patients to learn to contract their multifidus.9,10

Come learn more about the multifidus and how it relates to back pain and stability. In Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging: Women's Health and Orthopedic Topics we will go over how to help your patients learn to activate and strengthen their multifidus. Join me on February 28 - March 1st in Raleigh, NC to learn new ways to help your patients!

1. Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Multifidus muscle recovery is not automatic after resolution of acute, first‐episode low back pain. Spine 1996;21:2763–2769.

2. Russo M, Deckers K, Eldabe S, et al. Muscle control and non-specific chronic low back pain. Neuromodulation: Technology at the neural interface. 2018; 21 (1): 1-9.

3. D'Hooge R, Hodges P, Tsao H, Hall L, Macdonald D, Danneels L. Altered trunk muscle coordination during rapid trunk flexion in people in remission of recurrent low back pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2013;23:173–181

4. Massé‐Alarie H, Beaulieu L‐D, Preuss R, Schneider C. Corticomotor control of lumbar multifidus muscles is impaired in chronic low back pain: concurrent evidence from ultrasound imaging and double‐pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. Exp Brain Res 2015; 234:1033–1045.

5. Tsao H, Galea MP, Hodges PW. Driving plasticity in the motor cortex in recurrent low back pain. Eur J Pain 2010;14:832–839.

6. Seminowicz DA, Wideman TH, Naso L et al. Effective treatment of chronic low back pain in humans reverses abnormal brain anatomy and function. J Neurosci 2011;31:7540–7550

7. França FR, Burke TN, Caffaro RR, Ramos LA, Marques AP. Effects of muscular stretching and segmental stabilization on functional disability and pain in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2012;35:279–285.

8. Goldby LJ, Moore AP, Doust J, Trew ME. A randomized controlled trial investigating the efficiency of musculoskeletal physiotherapy on chronic low back disorder. Spine. 2006;31:1083–1093.

9. Ghamkhar L, Emami M, Mohseni‐Bandpei MA, Behtash H. Application of rehabilitative ultrasound in the assessment of low back pain: a literature review. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2011;15:465–477.

10. Van K, Hides JA, Richardson CA. The use of real‐time ultrasound imaging for biofeedback of lumbar multifidus muscle contraction in healthy subjects. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2006;36:920–925

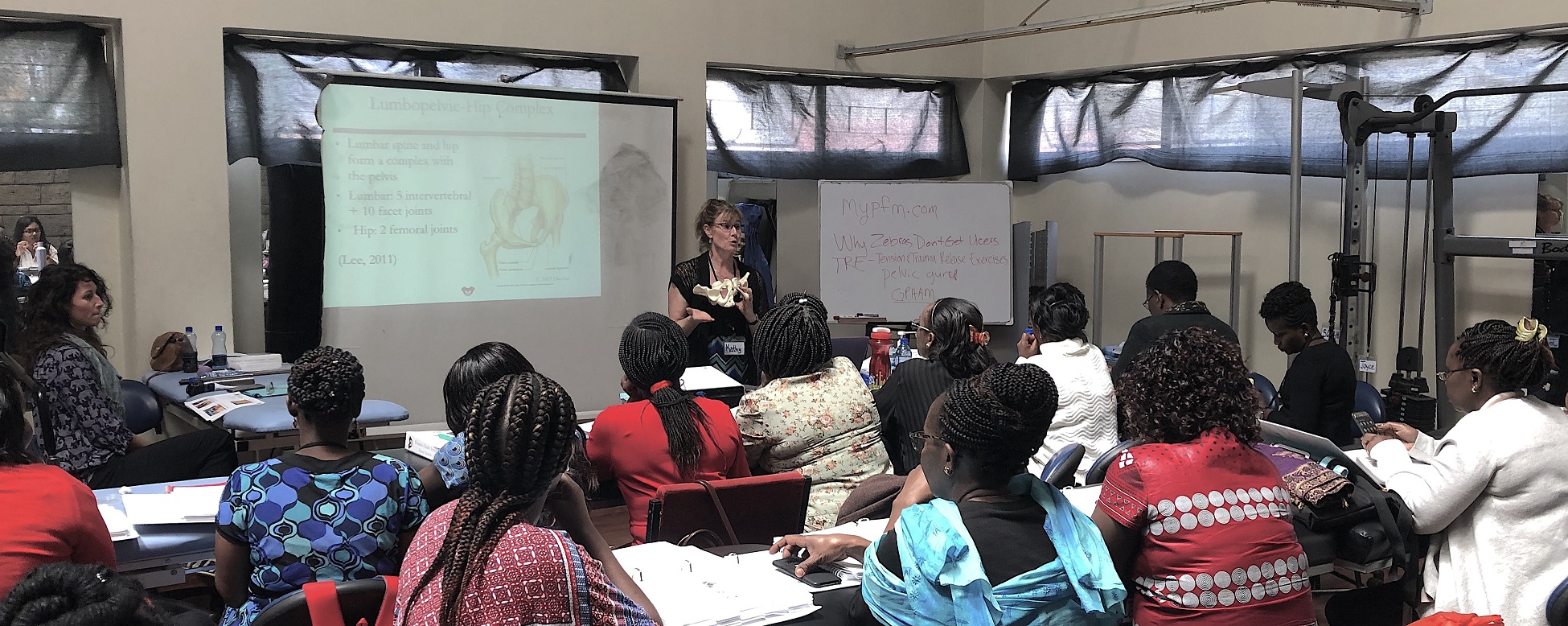

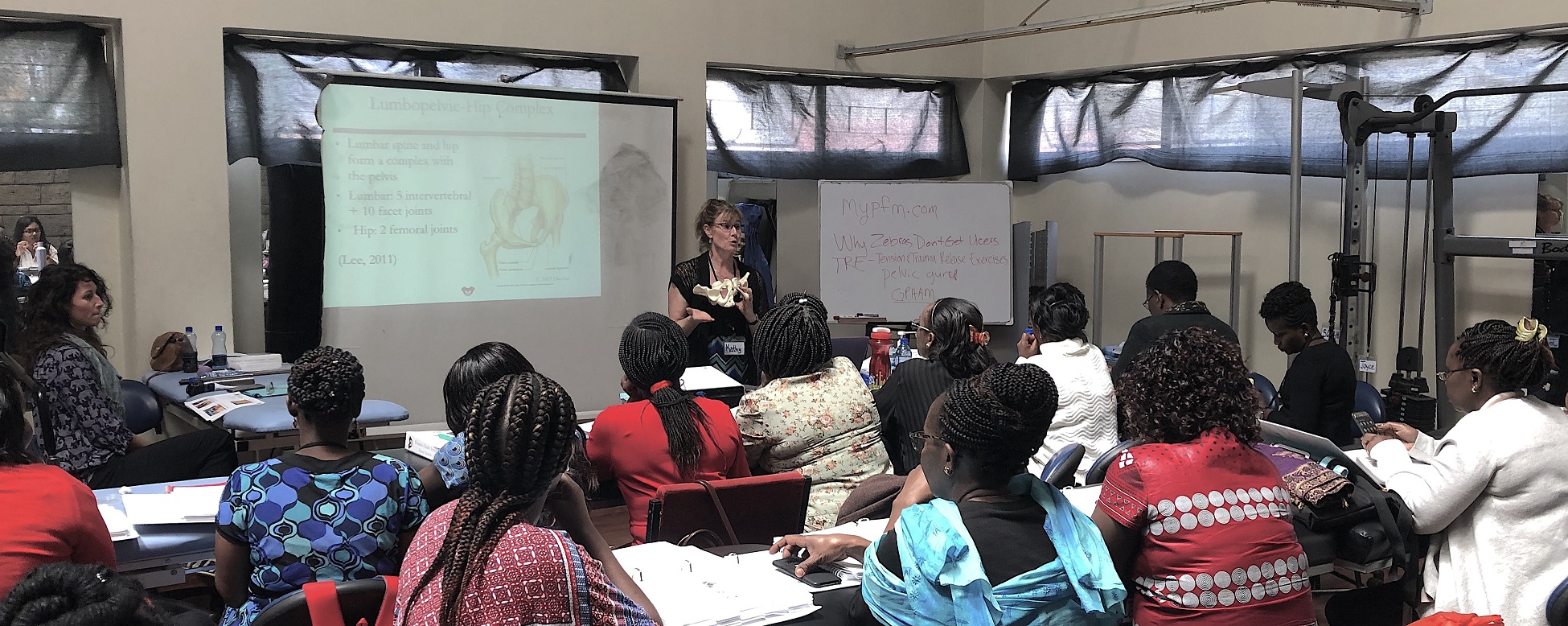

Earlier this year, Herman & Wallace sponsored the first ever pelvic rehab course for physios in Nairobi, Kenya in partnership with The Jackson Clinics Foundation. After returning from that course, Kathy Golic, PT spent months writing a new course, adapting information from Pelvic Floor Level 1, Level 2A, and the Pregnancy and Postpartum series. This October, Kathy (along with co-instructors Casie Danenhauer and Sherine Aubert) returned to teach her follow-up course that expanded on the first module, introducing lectures and labs tailored to the community of pelvic physios in Kenya. This dispatch comes from instructor Kathy Golic, PT, who sent in this article shortly after returning from the course. Huge thanks to Kathy and her colleagues Sherine Aubert and Casie Danenhauer for doing this important work!

It has been a week now, and as I type looking out on the windy rainy day, it is hard to believe that I was so recently in a warm, sheltered classroom sequestered from the hustle and bustle of Nairobi. A place which has captured my heart. Really it is the people, especially my new “sisters” who I spent so much time with during this last two-week course module. Once again, I experienced chill bumps every day from witnessing the growth, the stories, the wisdom and the compassion of these bright, motivated, committed physiotherapists who came back for the 2nd module in our series to help them become experts in the field of Pelvic Health. This module covered topics of Pregnancy, Postpartum care, Prolapse, Colorectal Conditions including fecal incontinence and constipation, and Coccydynia. We had a terrific printed course manual for this 2nd in the series, thanks to the partnership of Herman and Wallace and Jackson Clinics Foundation. With my wonderful and resourceful, skilled colleagues from LA, Casie Danenhaur, and Sherine Aubert, we included comprehensive lectures, lively demonstrations, hands on creative experiential learning opportunities, and awesome supervised lab training sessions. We also had a lot of case study discussions, and live case studies where we assisted the students, who are practicing physiotherapists, in conducting thorough assessments and clinical reasoning processes to treat and make plans to further the progress of their patients.

It has been a week now, and as I type looking out on the windy rainy day, it is hard to believe that I was so recently in a warm, sheltered classroom sequestered from the hustle and bustle of Nairobi. A place which has captured my heart. Really it is the people, especially my new “sisters” who I spent so much time with during this last two-week course module. Once again, I experienced chill bumps every day from witnessing the growth, the stories, the wisdom and the compassion of these bright, motivated, committed physiotherapists who came back for the 2nd module in our series to help them become experts in the field of Pelvic Health. This module covered topics of Pregnancy, Postpartum care, Prolapse, Colorectal Conditions including fecal incontinence and constipation, and Coccydynia. We had a terrific printed course manual for this 2nd in the series, thanks to the partnership of Herman and Wallace and Jackson Clinics Foundation. With my wonderful and resourceful, skilled colleagues from LA, Casie Danenhaur, and Sherine Aubert, we included comprehensive lectures, lively demonstrations, hands on creative experiential learning opportunities, and awesome supervised lab training sessions. We also had a lot of case study discussions, and live case studies where we assisted the students, who are practicing physiotherapists, in conducting thorough assessments and clinical reasoning processes to treat and make plans to further the progress of their patients.

All of this in itself was incredibly rewarding. But there was more. The power of sacrifice we witnessed. The power of solidarity and true generosity. Most of these women continued to have to work after class even while in this two-week module; in class from 8-4, but then going on their way, some of them through heavy Nairobi traffic, to treat patients in their offices, or to work hospital shifts. One student heading out after a Wed. afternoon class told me that she was going to work from 7- midnight, then would sleep until 4am, then back to work until 7 am, before returning to class at 8 am. She also had to miss one class to participate in her mentorship for her ortho advanced diploma, so had to make up a test with us the next day. (she aced the test!) Now for the generosity. I will share just 1 of many stories. One of the physios asked a patient of hers whom she felt she could use some help with, if she would mind traveling to the KMTC classroom where we were teaching so the other students could learn, while we the visiting instructors, would help guide in her assessment and care. This woman agreed, and got up at 3:30 am, traveled by bus for 3 hours to come for her treatment. She willingly shared her story, and it was tough to hear. She worked as a vegetable vendor carrying produce on her back, lifting it, and sitting on a stone for hours each day. She, a mother of 5 grown children with an unemployed husband. Her physio and the class did quite well in their assessment and with treatment and suggestions. She seemed pleased. Then as she prepared to leave, some of the physio students “passed the hat” and collected 7,000 kshillings (about $70.00) and presented this humble lady with the money so that she could afford transportation home. It is my understanding that most Kenyans spend 50% of their income on food, so sharing with this patient was a true sacrifice. But for these ladies, there was no question about it. This is how they live and how they work. They are themselves so grateful for the knowledge, skills and experience that they are getting through this program, and they will pay it backwards and forwards. My colleagues this time and last time, are also indebted to them for all they have taught us. It is truly an honor and privilege to be part of this great program, and I too am thankful for all the team players in this venture.

All of this in itself was incredibly rewarding. But there was more. The power of sacrifice we witnessed. The power of solidarity and true generosity. Most of these women continued to have to work after class even while in this two-week module; in class from 8-4, but then going on their way, some of them through heavy Nairobi traffic, to treat patients in their offices, or to work hospital shifts. One student heading out after a Wed. afternoon class told me that she was going to work from 7- midnight, then would sleep until 4am, then back to work until 7 am, before returning to class at 8 am. She also had to miss one class to participate in her mentorship for her ortho advanced diploma, so had to make up a test with us the next day. (she aced the test!) Now for the generosity. I will share just 1 of many stories. One of the physios asked a patient of hers whom she felt she could use some help with, if she would mind traveling to the KMTC classroom where we were teaching so the other students could learn, while we the visiting instructors, would help guide in her assessment and care. This woman agreed, and got up at 3:30 am, traveled by bus for 3 hours to come for her treatment. She willingly shared her story, and it was tough to hear. She worked as a vegetable vendor carrying produce on her back, lifting it, and sitting on a stone for hours each day. She, a mother of 5 grown children with an unemployed husband. Her physio and the class did quite well in their assessment and with treatment and suggestions. She seemed pleased. Then as she prepared to leave, some of the physio students “passed the hat” and collected 7,000 kshillings (about $70.00) and presented this humble lady with the money so that she could afford transportation home. It is my understanding that most Kenyans spend 50% of their income on food, so sharing with this patient was a true sacrifice. But for these ladies, there was no question about it. This is how they live and how they work. They are themselves so grateful for the knowledge, skills and experience that they are getting through this program, and they will pay it backwards and forwards. My colleagues this time and last time, are also indebted to them for all they have taught us. It is truly an honor and privilege to be part of this great program, and I too am thankful for all the team players in this venture.

Pelvic pain can often involve adverse neural tension. The hip and pelvic nerves wrap around like spaghetti, making diagnosis and treatment difficult. Is the pain driver boney, capsular, muscle or neurovascular? Luckily, impingement and labral tears are fairly easy to diagnosis. Nerve entrapment can be a little bit tricky to diagnosis and treat. Part of being a good pelvic floor physical therapist is appropriately diagnosing and then partnering with patients to treat symptoms, pain, and movement dysfunction.

The authors of this study focused on hip, so this blog focuses on sciatic and pudendal nerve entrapment in the athletic population. Nerve entrapment occurs when the normal slide and glide is limited. That can be from any structure in the pelvis and hip region that cause strain or compression on the nerves in the area. Often patient’s descriptions of pain can be the first sign with complaints of ‘burning’, ‘sharp’, or changes in sensation. Evaluation for changes in reflexes and motor function are helpful. Other signs of nerve entrapment are tenderness to palpation and reproduction of pain with movements that elongate the nerve. Medical management to confirm diagnosis include nerve blocks, and diagnostic imaging, and nerve conduction velocity tests.

The authors of this study focused on hip, so this blog focuses on sciatic and pudendal nerve entrapment in the athletic population. Nerve entrapment occurs when the normal slide and glide is limited. That can be from any structure in the pelvis and hip region that cause strain or compression on the nerves in the area. Often patient’s descriptions of pain can be the first sign with complaints of ‘burning’, ‘sharp’, or changes in sensation. Evaluation for changes in reflexes and motor function are helpful. Other signs of nerve entrapment are tenderness to palpation and reproduction of pain with movements that elongate the nerve. Medical management to confirm diagnosis include nerve blocks, and diagnostic imaging, and nerve conduction velocity tests.

Specific locations of pain can help determine where the nerve is being squished. The sciatic nerve (L4-S3) can be entrapped as it passes between the piriformis and deep hip rotators. This often presents with a history of trauma to the gluteal area and limited sitting tolerance (>30 minutes). As the sciatic nerve moves down it can have ischiofemoral impingement, when the nerve gets compressed between lateral ischial tuberosity and greater trochanter at level of quadratus femoris muscle. This will often present as pain during mid- to terminal-stance during walking. Then, once the sciatic nerve clears the pelvis it can become entrapped by the proximal hamstring. There can be hamstring trauma in the history, and possible partial avulsion or thickening of the hamstring may entrap the sciatic nerve.

The pudendal nerve (S2-S4) can become entrapped in several areas and symptoms often include pain medial to the ischium and can include genital regions for all genders, perineum, and peri-rectal regions. The most common areas consist of the space between the posterior pelvic ligaments (sacrospinous and sacrotuberous) and the obturator internus muscle. History often includes bike riding, and a common complaint is pain with sitting, except a toilet seat.

Differential diagnosis for posterior nerves physical examination can include the following tests:

Sciatic Nerve

- Seated palpation: where the clinician palpates the subgluteal space (between sacrum and deep hip rotators), ischial tuberosity and hamstring attachment, and in the area medial to ischial.

- Seated piriformis stretch - involved lower extremity is adducted and internally rotated while palpating posterior hip region.

- Active piriformis - resisted lateral abduction and external rotation while palpating posterior hip region.

- Ischiofemoral impingement: the involved is placed in extension with adduction and external rotation

- Active knee flexion: this test is done seated with knee at 30° and 90° flexion. Clinician palpates ischial canal while providing knee flexion resistance for 5 seconds in both positions.

Pudendal Nerve

- Palpation around sciatic notch, region medial ischium

- Internal palpation for obturator internus tenderness

- Internal palpation of alcocks canal

Consertative treatment including physical therapy can be helpful. Manual therapy including nerve glides and soft tissue mobilization. Nerve mobilizations require anatomical nerve pathway knowledge. Mobilizing the nerves is thought to improve blood flow within and around the nerve, decrease adhesions, and also may affect central sensitivity. Soft tissue mobilization is geared towards positively affecting scar tissue and encouraging movement that may be restricting neural movement.

Therapeutic exercises for strengthening and stretching are also helpful, however use caution to avoid aggressive stretching as it may aggravate nerves. Exercises to promote load transfer through the pelvis and lower extremities can be helpful. The authors also suggest lower extremity passive PNF (proprioceptive neurofacilitation) diagonal movements. The authors also suggest aerobic conditioning, cognitive behavioral therapy, and for the chronic pelvic pain population, pelvic floor muscle training that does not provoke symptoms.

When conservative treatment including injections produces limited results, surgical treatments are often the next step. Often surgeries where the nerves are decompressed, neurolysis, or removed, neurectomy can be helpful.

To learn more nerve assessment and treatment techniques, join Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC in her course Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment in Tampa, FL this December 6-8, 2019!

Martin R, Martin HD1, Kivlan BR 2.Nerve Entrapment In The Hip Region: Current Concepts Review.Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Dec;12(7):1163-1173.

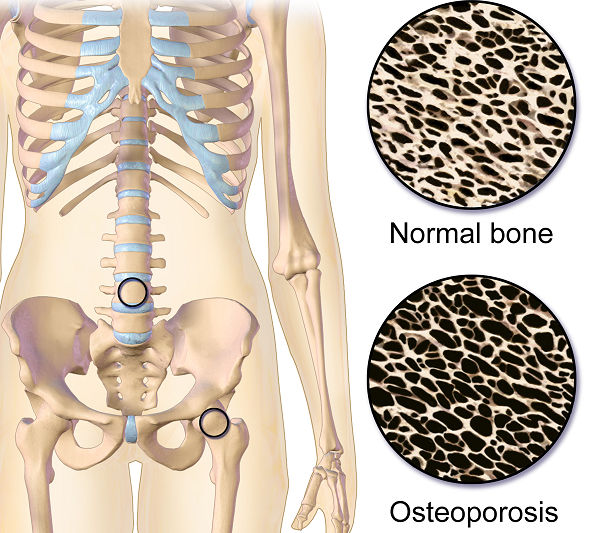

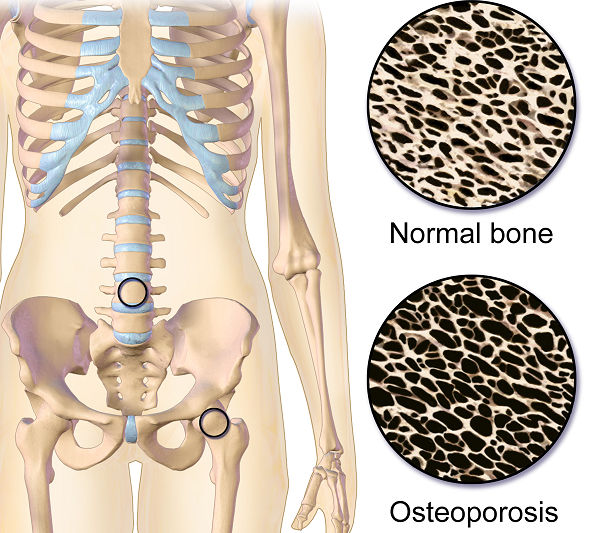

Do you work with osteoporosis patients? This may be a trick question because you probably do whether you know it or not- even if you are a pediatric therapist! Osteoporosis is defined by the World Health Organization1 as a systematic skeletal disease characterized by:

- Low bone mass

- Micro-architectural deterioration of bone tissue

- Consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to a fracture

Osteoporosis occurs in men, women and even children. It is sometimes called the “silent disease” because often people don’t know they have it until they break a bone. And even then, compression fractures are painful only 20-30% of the time. Old fractures are often found on x-rays when a person is imaged for illnesses such as pneumonia. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation2, about one in two women and one in four men over the age of 50 will suffer a fracture due to bone fragility. At this point in time, it is estimated 80% of patients entering Emergency Departments with a fragility fracture (a fall from a standing height) are never followed up for care.

Osteoporosis occurs in men, women and even children. It is sometimes called the “silent disease” because often people don’t know they have it until they break a bone. And even then, compression fractures are painful only 20-30% of the time. Old fractures are often found on x-rays when a person is imaged for illnesses such as pneumonia. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation2, about one in two women and one in four men over the age of 50 will suffer a fracture due to bone fragility. At this point in time, it is estimated 80% of patients entering Emergency Departments with a fragility fracture (a fall from a standing height) are never followed up for care.

As therapists, we see patients for a variety of diagnoses with co-morbidities but osteoporosis may not be listed. This could be because they have never been identified. We are in a prime position to screen for signs associated with the disorder. Below are the top 3 signs to look for:

- History of fracture from minimal trauma (fall from a standing height, sneeze, lifting groceries, etc.) The typical fracture areas are wrist, hip, and spine although fragility fractures can happen anywhere in the body.

- Hyper-kyphosis. Note, I said hyper-kyphosis, not kyphosis. We are meant to have a thoracic kyphosis but an excessive curve, particularly when it hinges around T8 area may indicate a collapse of the anterior portion of the vertebral bodies. This is the pie shaped wedging seen on x-rays and further increases the stress on the anterior aspect of the spine. Observe your patients’ sagittal posture for proper alignment.

- Loss of height. Ask your patient their tallest height remembered; then measure them. A loss of 4 cm (1.5 inches) or more may indicate fractures in the spine.

Remember pain may or may not accompany a compression fracture. Patients may complain of a “catch” or muscle spasm or nothing at all. These quick and simple screens can alert the healthcare provider and may help prevent further disintegration of the bones. Research is showing that not only weight bearing exercises but a site specific back and hip strengthening program decreases the risk of fracture.3

1. World Health Organization. www.who.int

2. National Osteoporosis Foundation. www.nof.org

3. Current Osteoporosis Reports. Sept, 2010. The Role of Exercise in the Treatment of Osteoporosis. Sinaki M, Pfeifer M, Preisinger E, Itoi E, Rissoli R, Boonen S, Geusens P, Minne HW.

Part 3: Carefully Choosing to Say Yes or No (or The Summer that Almost Wasn’t)

*Disclaimer: this essay is meant to be read in a voice of complete transparency and humility.

Two summers ago I was anxiously anticipating a break. I was wrapping up home school for my girls and had scheduled some down time from writing my contribution to “Boundaries, Meditation and Self-Care” when I got the call…

Two summers ago I was anxiously anticipating a break. I was wrapping up home school for my girls and had scheduled some down time from writing my contribution to “Boundaries, Meditation and Self-Care” when I got the call…

Rewind a bit. Two years prior I also got a call. Would I be interested in writing a chapter in a Urology textbook on alternative care for pelvic pain conditions…edited by and partnering with a big name in pelvic floor rehab? Oh yes indeed I would! I have always dreamed of seeing my name in print. Was I scared out of my mind? Heck yes! I was working 20 hours a week, part time home schooling my girls and teaching for Herman & Wallace. I had one day a week to myself for cleaning, errands, the occasional book reading or interacting with friends. I decided I could spend my next year of Fridays researching, writing and editing said chapter. Oh, I also started therapy for the anxiety increase that came with the project. My therapist suggested I hire help with house cleaning, which I did. She also suggested meditation, mindfulness and using essential oils. I opted not to enact these suggestions. It was a crazy year, but I learned a ton and was proud of my contribution to the publication.

In the brief time that I caught my breath from the book chapter, I was invited to be part of the team writing the Pelvic Floor Capstone course. What an honor! I had always wanted to try writing a course and this would be a perfect opportunity to collaborate with others on such a big project. I committed, worsening my anxiety with heart palpitations which escalated to a level that required medication. My Fridays and evenings were again occupied for quite some time. Luckily, I still had the cleaning help and the therapist which were really just the skinniest strings that were maintaining my sanity.

While teaching our first Capstone class, although both of us were struggling with burnout, Nari Clemons and I had a moment of euphoria, seeing everything come together and watching students learn. We decided we would design and write another course and put together an outline and a plan for Boundaries, Self-Care and Meditation.

I think you might be getting a picture of my prior lifestyle. If there was time, I filled it. If there was an opportunity, I took it. If I did something once, I could do it again. But applying the concepts of our boundaries course to myself changed everything.

Nari and I knew we were burning out and needed change. I have always had anxiety, but it had escalated to the point of requiring both therapy and medication. I was giving my all, my best, to everyone else and my family got my scrappy leftovers, the worse of me. I had been functioning in these patterns my whole life and had no idea how to get off the hamster wheel.

As we developed Boundaries, Meditation and Self Care I became my own research study, incorporating the material we would be teaching into my own life. I finally started setting priorities and boundaries that helped put my family first and give them the best of me. I said no to a variety of opportunities that I then delegated to colleagues who were delighted to step up. I started meditating, practicing mindfulness and using essential oils as part of my self-care as my therapist suggested a year ago. I even enrolled my kids in full time school for the upcoming year. I was feeling so much better!

So when the next call came, I was prepared.

The editor and famous pelvic floor PT I had worked with on the book chapter was in need of an editor for an article that was going to be published in a medical journal. There was a lot of editing that needed to be done and time was of the essence. My contribution as editor would list me as a co-author. How many of you also dream of seeing your name attached to an article in a peer reviewed medical journal? Because of what I had learned through therapy and practiced with meditation I had the ability to pause, reflect, and make an informed choice that considered how this opportunity lined up with my priorities. I replied with much gratitude for the offer, but this time I said no. It was difficult to say no, and I had to work through some regret, but in the end I made the right choice and we had a great summer.

Life is funny sometimes and lessons in humility are plentiful. Back track again to when the urology text came out a few years ago. I excitedly ordered a print copy. When I opened to the chapter which I contributed, I discovered another person’s name had accidently been printed where mine should have been. The mistake was corrected for the ebooks but more paper copies were not printed. I may never see my name in print, but the Summer That Almost Wasn’t taught me that there are more important things in life.

If you find yourself struggling with boundaries, saying no, and prioritizing the things that are important to you personally and as a therapist, know that you are not alone, and you can get support. Consider talking with your supervisor, a counselor, reading a good book on the subject or taking Boundaries, Meditation and Self Care, a course offering through Herman and Wallace that was designed to help pelvic health professionals stay healthy and inspired while equipping therapists with new tools to share with their patients.

We hope you will join us for Boundaries, Meditation and Self Care this November 9-11, 2019 in San Diego, CA.

Childbirth fear is associated with lower labor pain tolerance and worse postpartum adjustment.1,2 In addition, psychological distress during pregnancy is associated with adverse consequences in offspring, including detrimental birth outcomes, long-term defects in cognitive development, behavioral problems during childhood and high levels of stress-related hormones.3 These negative consequences of fear and stress during pregnancy have inspired both interest and research into the role of mindfulness training during pregnancy to reduce fear and stress and improve outcomes.

In a randomized controlled trial, first-time mothers in the late 3rd trimester of pregnancy were randomized to attend either a 2.5-day mindfulness-based childbirth preparation course offered as a weekend workshop or a standard childbirth preparation course with no mind-body focus.4 Participants completed self-report assessments pre-intervention, post-intervention, and post-birth, and medical record data were collected. Compared to standard childbirth education, those in the mindfulness-based workshop showed greater childbirth self-efficacy and mindful body awareness, reduced pain catastrophizing and lower post-course depression symptoms that were maintained through postpartum follow-up. Participants in the mindfulness workshop also demonstrated a trend toward a lower rate of opioid analgesia use in labor.

In a qualitative study, researchers conducted in-depth interviews at four to six months postpartum with ten mothers at increased risk of perinatal stress, anxiety and depression and six fathers who had participated in a Mindfulness Based Childbirth and Parenting Program (MBCP).5 The MBCP program integrates mindfulness training into childbirth education. Participants meet for eight 2 hour and 15 minute weekly sessions and a reunion after babies are born. Specific mindfulness practices introduced include body scan, mindful movement, sitting meditation and walking meditation. Also, methods to integrate mindfulness into pain management, parenting and activities of daily living are introduced. Participants are asked to practice at home for 30 min per day in between sessions supported by audio guided instructions and informative texts.

Participants in the MBCP Program described gaining new skills for coping with stress, anxiety and pain, as well as developing insight and self-compassion and improving communication. Participants attributed these improvements to an increased ability to focus and gain a wider perspective as well as adopt attitudes of curiosity, non-judging and acceptance. In addition, they described mindfulness training to be helpful for coping with childbirth and parenting, including breastfeeding troubles, sleep deprivation and stressful moments with the baby.

These findings demonstrate potential therapeutic outcomes of integrating mindfulness training into childbirth preparation. Although this is a young field and more research is warranted, there is substantial research demonstrating mindfulness training improves stress management, pain management and decreases physiological markers of stress in a wide range of patient populations.6, 7 While the interventions in the above two studies introduce mindfulness in a group format, I have also found that patients can greatly benefit from being taught mindful principles and practices in one-on-one treatment sessions.

Carolyn will share her over-30 years of training and experience teaching mindfulness to patients both individually and in group settings in her course, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment, coming up on October 26 and 27 in Houston, TX. Participants will return to the clinic with skills to not only help patients, but to also help themselves be less stressed, more mindful providers!

1. Alehagen S, Wijma K, Wijma B. Fear during labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(4): 315–320.

2. Laursen M, Johansen C, Hedegaard M. Fear of childbirth and risk for birth complications in nulliparous women in the Danish national birth cohort. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009:116(10): 1350–1355.

3. Isgut M, Smith AK, Reimann. The impact of psychological distress during pregnancy on the developing fetus: Biological mechanisms and potential benefits of mindfulness interventions. J Perinat Med. 2017 Dec 20;45(9):999-1011.

4. Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Chao MT. The benefits of preparing for childbirth with mindfulness training: a randomized controlled trial with an active comparison. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017. May 12;17(1):140.

5. Lonnberg G, Nissen E, Niemi M. What is learned from Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting Education? – Participants’ experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18: 466.

6. Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(2):199-213.

7. Pascoe MC, Thompson DR, Jenkins ZM, Ski CF. Mindfulness mediates the physiological markers of stress: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:156-78.

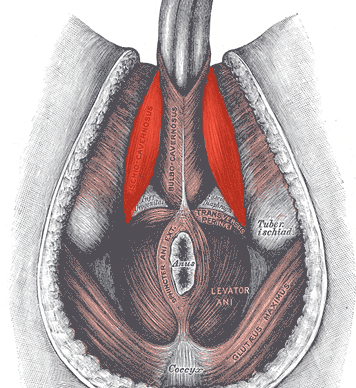

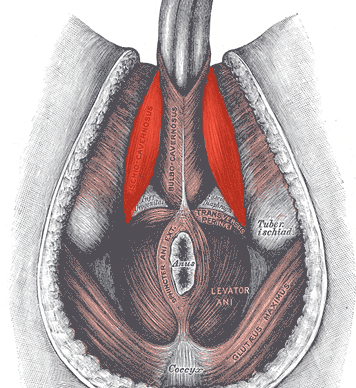

Often pelvic floor therapists see men for post-prostatectomy urinary leakage. However, at least for me, that quickly led to seeing male patients for pelvic pain and sexual dysfunction. Male sexual dysfunction is a broad category and can consist of erectile dysfunction (ED), ejaculation disorders including premature ejaculation (PE), and low libido -- often there is a pelvic floor muscle (PFM) dysfunction component. Conservative treatment frequently consists of pharmacological and lifestyle changes for this population.

In normal sexual function, the male superficial pelvic floor musculature (bulbocavernosus and ischiocavernosus) work together to create increased intracavernosus pressure by limiting venous return, resulting in an erection. Ejaculation is created by rhythmic contractions of the bulbocavernosus muscle.

The authors of this systematic review were curious if pelvic floor muscle training was effective for treating erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation diagnoses, and if so to determine whether there is a treatment protocol. Ten studies were found that met the inclusion criteria, five that focused on ED and five that focused on PE. In total, there were 668 participants ranging in age from 30-59 years old. Studies were excluded if participants were post-prostatectomy and/or had a neurological diagnosis. The intervention was a pelvic floor program, and pelvic floor muscle contractions were either taught or supervised. Studies also included supportive treatment including biofeedback, lifestyle changes, and electrical stimulation.

The authors of this systematic review were curious if pelvic floor muscle training was effective for treating erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation diagnoses, and if so to determine whether there is a treatment protocol. Ten studies were found that met the inclusion criteria, five that focused on ED and five that focused on PE. In total, there were 668 participants ranging in age from 30-59 years old. Studies were excluded if participants were post-prostatectomy and/or had a neurological diagnosis. The intervention was a pelvic floor program, and pelvic floor muscle contractions were either taught or supervised. Studies also included supportive treatment including biofeedback, lifestyle changes, and electrical stimulation.

The studies focused on erectile dysfunction listed a combination of hormonal, psychogenic, arteriogenic, and venogenic causes. The pelvic floor training ranged from 5-20 visits over 3-4 months and included a home exercise program. Pelvic floor training was similar in all studies and consisted of maximal quick contractions over one second and submaximal endurance holds over 6-10 seconds. Compliance to home exercise program was not assessed. Between 35% and 47% of participants reported a full resolution of symptoms. Subjective improvements were supported by improved maximal anal pressure and intracavernosus pressure. One study used the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and showed significant improvement (p<0.05).

The studies focused on premature ejaculation noted participants had either lifelong or secondary PE. The pelvic floor training in these studies ranged from 12-20 sessions over 1-3 months. All studies used electrical stimulation as part of the pelvic floor muscle training. Four studies also used biofeedback. Only one study listed a home exercise program but did not report on compliance. The pelvic floor muscle training was compared to nothing in three studies, and to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) in the other two studies. Patient reported full resolution of symptoms was 55-83% in two studies, and there was a significant improvement in delay in heterosexual penetrative ejaculation (p<0.05) in three studies.

For both erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation, pelvic floor muscle exercise prescription was 2-3 times per week with pelvic floor muscle contractions both maximal quick contractions and submaximal endurance holds. Significant results were shown with participants who were taught pelvic floor muscle contractions through a combination of verbal and physical means (typically biofeedback). Specific verbal cues were not reported. The authors suggest that electrical stimulation was helpful for training recruitment patterns; however, there was not a significant difference in outcomes for those with ED when using electrical stimulation. The authors suggest that pelvic floor muscle training can be part of a conservative treatment. It may be used with oral pharmacology for quick results, and may be beneficial with electrical stimulation and biofeedback, though more research is indicated.

If you are interested in learning more about treating male patients, consider attending Male Pelvic Floor: Function, Dysfunction, and Treatment!

Myers, C., Smith, M. “Pelvic floor muscle training improves erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation: a systematic review” Physiotherapy 105 (2019) 235–243