In this post, we want to give a high-level overview of interstitial cystitis and an introduction to other resources if you’d like to dive deeper into treatment the condition. There’s a printable, patient-friendly version of this overview if you’d like to use it in describing the condition with patients. In addition, you may want to review the 8 Myths of Interstitial Cystitis series and the AUA Guidelines for Interstitial Cystitis.

Definition

Interstitial cystitis is defined as pain or pressure perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than six weeks duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes.

Unfortunately, for physicians, pelvic floor dysfunction falls under category of ‘unidentifiable cause.’ Interstitial cystitis is really more of a description of symptoms, rather than a discrete diagnosis, and the condition presents in many different ways.

Symptoms

The hallmarks of interstitial cystitis are pelvic pain, often in the suprapubic area or inner thighs, and urinary urgency and frequency. Other common symptoms include pain with intercourse, nocturia, low back pain, constipation, and urinary retention.

Many patients are surprised to realize that symptoms like painful intercourse, low back pain, and constipation are related to their IC diagnosis. This challenges the misconception that issues are arising solely from the bladder, and is a good way to help patients (and their physicians) understand that IC is about more than just the bladder.

Diagnosis

Interstitial cystitis is fundamentally a diagnosis of exclusion. Most patients suspect a urinary tract infection (UTI) when their symptoms first present. It’s actually common for symptoms to start as the result of a UTI, and simply not resolve once the infection has cleared. Patients are often treated with multiple rounds of antibiotics for these ‘phantom’ UTIs, where cultures have come back negative, before an IC diagnosis is considered.

It’s important for us as physical therapists to be able to share with patients that no testing is required to confirm an IC diagnosis, it can be diagnosed clinically. In practice, a urologist will likely want to conduct a cystoscopy, which can rule out more serious issues like bladder cancer as well as check for Hunner’s lesions (wounds in the bladder that are present in about 10% of IC patients). However, after that, no additional testing is needed. The potassium sensitivity test (PST) was formerly used by some urologists, but it has been shown to be useless diagnostically and extremely painful for patients and is not recommended by the American Urological Association. Urodynamic testing is also often conducted, but again is not necessary to establish an IC diagnosis.

Physical Therapy for IC

According to the American Urological Association, physical therapy is the most proven treatment for interstitial cystitis. It’s given an evidence grade of ‘A’ (the only treatment with that grade) and recommended in the first line of medical treatment.

In controlled clinical trials, manual physical therapy has been shown to benefit up to 85% of both men and women. These trials reported benefits after ten visits of one-hour treatment sessions.

In a study conducted at our clinic , PelvicSanity, we found that physical therapy was able to reduce pain for IC patients from an average of 7.6 (out of 10) before treatment to 2.6 following physical therapy. Similarly, how much their symptoms bothered patients fell from 8.3 to 2.8. More than half of patients reported improvements within the first three visits.

Unfortunately, many patients still aren’t referred to pelvic physical therapy by their physician. More than half of the patients in the study had seen more than 5 physicians before finding pelvic PT, and only 7% of patients felt they had been referred to physical therapy at the appropriate time by their doctor.

Multi-Disciplinary Approach

Patients with interstitial cystitis or pelvic pain always benefit from a multidisciplinary approach to treatment.This can include:

- Stress relief to downregulate the nervous system can decrease symptoms and reduce flares. Gentle exercise, meditation, yoga, deep breathing, or working with a psychologist can all provide benefits for patients.

- Diet and nutrition are important when working with IC patients. There is no formal ‘IC Diet’, but most patients are sensitive to at least a few trigger foods. The gold standard of treatment is an elimination diet, where the common culprits are completely removed from the diet and then added back in one at a time. This identifies which foods are triggers for patients. With nutrition for IC, patients should avoid their personal trigger foods and eat healthy – it doesn’t have to be any more restrictive or complicated.

- Alternative treatments like acupuncture have been shown to reduce pelvic pain in patients, and several supplements have shown benefits in trials or anecdotally among patients.

- Bladder treatments include instillations and nerve stimulation. Some patients may benefit from bladder instillations, but many others find that the process of the instillation actually causes additional symptoms. If instillations are beneficial, patients should be encouraged to address the underlying issues during the reprieve that instillations bring. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation or an implanted nerve stimulation device can both be possible treatment options.

- Oral medications can also reduce symptoms, but do not address the underlying cause of symptoms in patients. Medication that dampens the nervous system, often an anti-depressant or similar medication, can reduce pain and hypersensitivity. Anti-inflammatories may be beneficial in lowering inflammation and helping break the cycle of dysfunction-inflammation-pain. Most patients are started on Elmiron®, the only FDA-approved medication for IC; unfortunately, in the most recent clinical trial research Elmiron has been shown to be no more effective than a placebo. If it is effective, it only is beneficial for about one-third of patients, and many won’t be compliant with the drug due to cost and side effects.

Nicole Cozean, PT, DPT, WCS (www.pelvicsanity.com/about-nicole) is the founder of PelvicSanity physical therapy in Southern California. Name the 2017 PT of the Year by the ICN, she’s the first physical therapist to serve on the Interstitial Cystitis Association’s Board of Directors and the author of the award-winning book The IC Solution (www.pelvicsanity.com/the-ic-solution). She teaches at her alma mater, Chapman University, as well as continuing education through Herman & Wallace. Nicole also founded the Pelvic PT Huddle (www.facebook.com/groups/pelvicpthuddle), an online Facebook group for pelvic PTs to collaborate.

Nicole Cozean, PT, DPT, WCS (www.pelvicsanity.com/about-nicole) is the founder of PelvicSanity physical therapy in Southern California. Name the 2017 PT of the Year by the ICN, she’s the first physical therapist to serve on the Interstitial Cystitis Association’s Board of Directors and the author of the award-winning book The IC Solution (www.pelvicsanity.com/the-ic-solution). She teaches at her alma mater, Chapman University, as well as continuing education through Herman & Wallace. Nicole also founded the Pelvic PT Huddle (www.facebook.com/groups/pelvicpthuddle), an online Facebook group for pelvic PTs to collaborate.

Interstitial Cystitis Course

In our upcoming course for physical therapists in treating interstitial cystitis (April 6-7, 2019 in Princeton, New Jersey), we’ll focus on the most important physical therapy techniques for IC, home stretching and self-care programs, and information to guide patients in creating a holistic treatment plan. The course will delve into how to handle complex IC presentations. It’s a deep dive into the condition, focusing not just on manual treatment techniques but also how to successfully manage an IC patient from beginning to resolution of symptoms.

Additional Resources

- Interstitial Cystitis Overview (printable)

- The Interstitial Cystitis Solution

- Patient groups include the Interstitial Cystitis Association (ICA) (www.ic-help.org) and the IC Network (www.ic-network.com), which both have fantastic resources for patients.

- The AUA Guidelines for IC

- IC Flare-Busting Plan

Birthing can be an unpredictable process for mothers and babies. With cases of fetal distress, the baby can require rapid delivery. Alternatively, in cases with cephalo-pelvic disproportion, the baby has a larger head, or the mother has a decreased capacity within the pelvis to allow the fetus to travel through the birthing canal. Additionally, the baby may have posterior presentation, colloquially known as “sunny side up” in which the baby’s occipital bone is toward the sacrum. With any of these situations, it is good to know c-sections are an option to safely deliver the child.

Women may also be inclined to try to get a c-section to avoid pelvic complication or tears or because of a history of a severe prior tear. As pelvic therapists, we know that the number of vaginal births and history of vaginal tears increase the risk of urinary incontinence and prolapse. Yet, many therapists are unfamiliar with the effects of c-section and the impact of rehab for diastasis.

Women may also be inclined to try to get a c-section to avoid pelvic complication or tears or because of a history of a severe prior tear. As pelvic therapists, we know that the number of vaginal births and history of vaginal tears increase the risk of urinary incontinence and prolapse. Yet, many therapists are unfamiliar with the effects of c-section and the impact of rehab for diastasis.

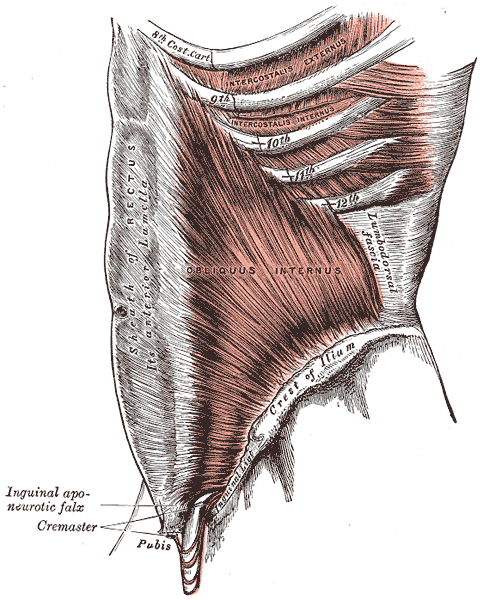

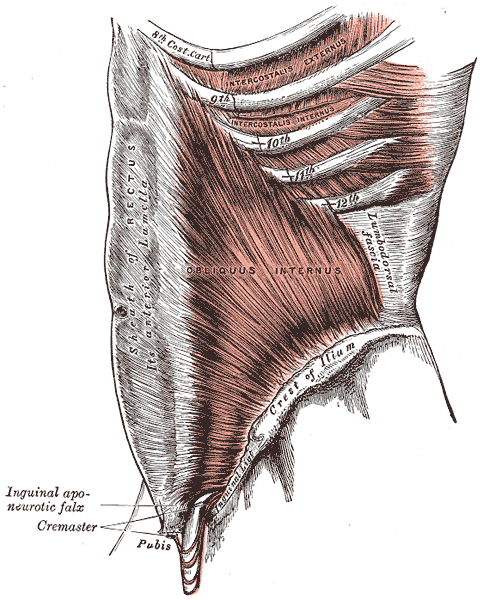

A 2008 dissection study of 37 cadavers studied the path of the ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves. The course of the nerves was compared with standard abdominal surgical incisions, including appendectomy, inguinal, pfannestiel incisions (the latter used in cesarean sections). The study concluded that surgical incisions performed below the level of the anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS) carry the risk of injury to the ilioinguinal and iloiohypogastric nerves 1. Another 2005 study reported low transverse fascial incision risk injury to the ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves, and the pain of entrapment of these nerves may benefit from neurectomy in recalcitrant cases.2

Why does injury to the nerves matter? After pregnancy, patients may need rehab and retraining of their abdominal recruitment patterns for diastasis and stability. The ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves are the innervation for both the transverse abdominus and the obliques below the umbilicus. When we are working to retrain the muscles, certainly neural entrapment or poor firing can greatly impact the success of our intervention as rehab professionals. Interestingly, a study from Turkey showed patients had a significant increase in diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) with a history of 2 cesarean sections and increased parity and recurrent abdominal surgery increase the risk of DRA.2

A fourth study looked at 23 patients with ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerve entrapment syndrome following transverse lower abdominal incision (such as a c-section). In this study, the diagnostic triad of ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerve entrapment after operation was defined as 1) typical burning or lancinating pain near the incision that radiates to the area supplied by the nerve, 2). Clear evidence of impaired sensory perception of that nerve, and 3) pain relieved by local anaesthetic.4

One of the other symptoms we may see in an area of nerve damage is a small outpouching in the area of decreased innervation on the front lower abdominal wall.

So, what can we do with this information? The good news is that as rehab professionals, we can treat along the fascial pathway of the nerve to release in key areas of entrapment. We can mobilize the nerve directly. Neural tension testing can help us differentiate the nerve in question and we can use neural glides and slides after having freed up the nerve from the area of compression. Then, we can increase the communication of the nerve with the muscles by using specific, localized strengthening and stretch in areas of prior compression. All of these techniques are taught in in our course, Lumbar Nerve Manual Treatment and Assessment. Come join us in San Diego May 3-5, 2019 to learn how to differentially diagnose and treat entrapment of all of the nerves of the lumbar plexus.

Okiemy, G., Ele, N., Odzebe, A. S., Chocolat, R., & Massengo, R. (2008). The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. The anatomic bases in preventing postoperative neuropathies after appendectomy, inguinal herniorraphy, caesareans. Le Mali medical, 23(4), 1-4.

Whiteside, J. L., & Barber, M. D. (2005). Ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric neurectomy for management of intractable right lower quadrant pain after cesarean section: a case report. The Journal of reproductive medicine, 50(11), 857-859.

Turan, V., Colluoglu, C., Turkuilmaz, E., & Korucuoglu, U. (2011). Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in the population of young multiparous adults in Turkey. Ginekologia polska, 82(11).

Stulz, P., & Pfeiffer, K. M. (1982). Peripheral nerve injuries resulting from common surgical procedures in the lower portion of the abdomen. Archives of Surgery, 117(3), 324-327.

This post is a follow-up to the February 20th post written by Nancy Cullinane, "Pelvic Floor One is Heading to Kenya"

By the time folks are reading this, Nancy Cullinane, PT, MHS, WCS, Terri Lannigan, PT, DPT, OCS, and I will likely be in a warm, crowded classroom in Nairobi, Kenya helping 30+ “physios” navigate the world of misbehaving bladders, detailed anatomy description, and their first internal lab experiences. No doubt it will be both challenging and extremely rewarding. We are so grateful to the Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehab Institute for sharing their curriculum in partnership with the Jackson Clinics Foundation to allow us to offer their valuable curriculum in order to affect positive health care changes.

I personally am humbled and honored to get to play a small but key role in the development of foundational knowledge and skills for these women PT’s who will no doubt change the lives of countless Kenyan women, and, consequently, their families.

My adventure truly began when I offered to write lectures on the topics of Fistula and FGM/C (female genital mutilation/cutting) and I began the process of crash course learning about these topics. The quest has taken me on a deep dive into professional journals, NGO websites, surgical procedure videos and insightful interviews with some of the pioneers working for years including “in the field” to help women in Africa and in countries where these issues are prevalent.

Before I began my research on the topic of fistula, I pretty much thought of a fistula as a hole between two structures in the body where it doesn’t belong, and narrowly thought of in terms of anal fistulas, acknowledging how lucky we are that there are skilled colorectal surgeons who can fix them. But after more research, my world view changed. (Operative word here being “world”).

A fistula is an abnormal or surgically made passage between a hollow or tubular organ and the body surface, or between two hollow or tubular organs. For our purposes here today, I am referring to an abnormal hole or passage between the vagina and the bladder, or rectum, or both. When the fistula forms, urine and/or stool passes through the vagina. The results are that the woman becomes incontinent and cannot control the leakage because the vagina is not designed to control these types of body fluids.

According to the Worldwide Fistula Fund, there are ~ 2 million women and girls suffering from fistulas. Estimates range from 30 to 100 thousand new cases developing each year; 3-5 cases/1000 pregnancies in low-income countries. A woman may suffer for 1-9 years before seeking treatment. For women who develop fistula in their first pregnancy, 70% end up with no living children.

Vesicovaginal fistulas (VVF) can involve the bladder, ureters, urethra, and a small or large portion of the vaginal wall. Women with VVF will complain of constant urine leakage throughout the day and night, and because the bladder never fills enough to trigger the urge to void, they may stop using the toilet altogether. During the exam there may be pooling of urine in the vagina.

Rectovaginal Fistula is less common, and accounts for ~ 10% of the cases. Women with RVF complain of fecal incontinence and may report presence of stool in the vagina. These women often will also have VVF.

In Kenya, most fistulas are obstetric fistulas, which occur as a result of prolonged obstetric labor (POL). These are also called gynecologic, genital, or pelvic fistulas. Traumatic fistulas account for 17-24 % of the cases and are caused by rape, sexual or other trauma, and sometimes even from FGM/C. The other type of fistula by cause is iatrogenic, meaning unintentionally caused by a health care provider during procedures such as during a C-section, hysterectomy, or other pelvic surgery. Most fistulas seen in the US are of this type.

Prolonged Obstructed Labor most often occurs when the infant’s head descends into the pelvis, but cannot pass though because of cephalo-pelvic disproportion (mismatch between fetus head and mother’s pelvis) thus creating sustained pressure on the tissues separating the tissues of the vagina and bladder or rectum, (or both) leading to a lack of blood flow and ultimately to necrosis of the tissue, and the development of the fistula. Those who develop this type of fistula spend an average of 3.8 days in labor (start of uterine contractions), some up to a week. In these cases, family members or traditional birth attendants may not recognize this is occurring, and even if they do, they may not have the instrumentation, the facilities or the skills necessary to handle the situation with an instrumental delivery or a C-section. And many of these women are in remote locations without transportation to appropriate facilities or lack the money to pay for procedures.

There are many adverse events and medical consequences that can result as a result of untreated obstetrical fistulas including the death of the baby in 90% of the cases. Physical effects besides the incontinence previously mentioned can include lower extremity nerve damage, which can be disabling for these women, along with a host of other physical and systemic health issues. The social isolation, ostracization by community, divorce, and loss of employment can lead to depression, premature lifespan, and sometimes suicide.

The good news is there are several great organizations making a difference.

In most cases, surgery is needed to repair the fistula. Sometimes, however, if the fistula is identified very early, it may be treated by placing a catheter into the bladder and allowing the tissues to heal and close on their own, and this is more viable in high-income countries after iatrogenic fistulas, but unfortunately, most women in the low-income countries have to wait for months or years before they receive any medical care.

There is an 80-90% cure rate depending on the severity, but according to the Worldwide Fistula Fund, 90% are left untreated, as the treatment capacity is only around 15,000 per year for the 100,00 new patients requiring it. Prevention is vital.

Despite successful repair of vesicovaginal fistulas, research shows that 15-35% of women report post-op incontinence at the time of discharge from the hospital, and that 45-100% of women may become incontinent in the years following their repair. Studies suggest that scar tissue-fibrosis of the abdominal wall and pelvis, and vaginal stenosis are strongly associated with post-operative incontinence.

According to research by Castille, Y-J et al in Int. J Gynecology Obstet 2014, there can be improved outcome of surgery both in terms of successful closure of vesicovaginal fistula and reduced risk of persistent urinary incontinence if women are taught a correct pelvic floor muscle contraction and advised to practice PFM exercise. Other studies have shown a positive effect from pre and post op PT in both post op urinary incontinence and PFM strength and endurance with a reduction of incontinence in more than 70% of treated patients, with improvements maintained at the 1year follow up. SO, THIS IS ONE REASON WE ARE SO EXCITED TO BE GOING TO KENYA!

I inquired about the use of dilators via email communication with surgeon Rachel Pope , MD MPH who has done extensive work in Malawi with women who have suffered from fistula, including the use of dilators, and her response was: “in women who have had obstetric fistula the dilators seem only marginally helpful after standard fistula repairs. The key is to have a good vaginal reconstructive surgery where skin flaps that still maintain their blood supply replace the area in the vagina previously covered by scar tissue. The dilators work exceedingly well when there is healthy tissue in place, and I think the overall outcomes are better for women in those scenarios compared to the cement-like scar we often see in women with fistulas.”

In the US, there are specialist surgeons who provide surgical repairs. While genitourinary fistulas can occur because of obstructed labor and operative deliveries in high income countries, they can also occur in a variety of pelvic surgeries, post pelvic radiation, as well as in cases of cancer, infections, with stones, and as well etiology includes instrumentations such as D&Cs, catheters, endoscopic trauma, and pessaries, and as well in cases of foreign bodies, accidental trauma, and for congenital reasons. As pelvic therapists it is important to know your patients’ surgical and medical history and to pay special attention to the patient’s history regarding their incontinence description and onset and be mindful during exam to notice possible pooling of urine in the vagina. Though rare in terms of occurrence, we should be aware of the possibility and may play a role in referring the patient to a physician who can do further diagnostic testing

In conclusion, I want to thank UK physiotherapist Gill Brook MCSP (DSA) CSP MSC, president of the IOPTWH who shared with me by interview her knowledge of fistula and experiences with the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital in Ethiopia, which she has been visiting for 10 years, as well as Seattle’s Dr. Julie LaCombe MD FACOG who has performed fistula surgeries in Uganda and Bangladesh and met with me personally to share about obstetrical trauma and fistula surgery and management.

Nancy, Terri and I will look forward to sharing photos and more about our journey and experiences, upon our return. In the meantime, check out the Campaign to End Fistula and join the campaign.

Does cognitive self-regulation influence the pain experience by modulating representations of nociceptive stimuli in the brain or does it regulate reported pain via neural pathways distinct from the one that mediates nociceptive processing? Woo and colleagues devised an experiment to answer this question.1 They invited thirty-three healthy participants to undergo fMRI while receiving thermal stimulation trial runs that involved 6 levels of temperatures. Trial runs included “passive experience” where participants passively received and rated heat stimuli, and “regulation” runs, where participants were asked to cognitively increase or decrease pain intensity.

Instructions for increasing pain intensity included statements such as “Try to focus on how unpleasant the pain is. Pay attention to the burning, stinging and shooting sensation.” Instructions for decreasing pain intensity included statements such as “Focus on the part of the sensation that is pleasantly warm. Imagine your skin is very cool and how good the stimulation feels as it warms you up.” The effects of both manipulations on two brain systems previously identified in the literature were examined. One brain system was the “neurological pain signature” (NPS), a distributed pattern of fMRI activity shown to specifically track pain intensity induced by noxious inputs. The second system was the pathway connecting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) with the nucleus accumbens (NAc), shown to play a role in both reappraisal and modulation of pain. In humans, the vmPFC tracks spontaneous pain when it has become chronic and potentially dissociated from nociception.2,3 In patients with sub-acute back pain, the vmPFC-NAc connectivity has been shown to predict subsequent transition to chronic back pain.4 In addition, the vmPCF is hypothesized to play a role in the construction of self-representations, assigning personal value to self-related contents and, ultimately, influencing choices and decisions.5

Instructions for increasing pain intensity included statements such as “Try to focus on how unpleasant the pain is. Pay attention to the burning, stinging and shooting sensation.” Instructions for decreasing pain intensity included statements such as “Focus on the part of the sensation that is pleasantly warm. Imagine your skin is very cool and how good the stimulation feels as it warms you up.” The effects of both manipulations on two brain systems previously identified in the literature were examined. One brain system was the “neurological pain signature” (NPS), a distributed pattern of fMRI activity shown to specifically track pain intensity induced by noxious inputs. The second system was the pathway connecting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) with the nucleus accumbens (NAc), shown to play a role in both reappraisal and modulation of pain. In humans, the vmPFC tracks spontaneous pain when it has become chronic and potentially dissociated from nociception.2,3 In patients with sub-acute back pain, the vmPFC-NAc connectivity has been shown to predict subsequent transition to chronic back pain.4 In addition, the vmPCF is hypothesized to play a role in the construction of self-representations, assigning personal value to self-related contents and, ultimately, influencing choices and decisions.5

Woo and colleagues found that both heat intensity and self-regulation strongly influenced reported pain, however they did so by two differing pathways. The NPS mediated only the effects of nociceptive input. The self-regulation effects on pain were mediated by the NAc-vmPFC pathway, which was unresponsive to the intensity of nociceptive input. The NAc-vmPFC pathway responded to both “increase” and “decrease” self-regulation conditions. Based on these results, study authors suggest that pain is influenced by both noxious input and cognitive self-regulation, however they are modulated by two distinct brain mechanisms. While the NPS encodes brain activity closely tied to primary nociceptive processing, the NAc-vmPFC pathway encodes information about evaluative aspects of pain in context. This research is limited in that the distinction between pain intensity and pain unpleasantness was not included and the subjects were otherwise healthy. Further research is warranted on the effects of this cognitive self-regulation model on brain pathways in patients with chronic pain conditions.

Even with the noted limitations, this research invites the clinician to consider the role of both nociceptive mechanisms and cognitive self-regulatory influences on a patient’s pain experience and suggests treatment choices should take both factors into consideration. Mindful awareness training is a treatment that contributes to cognitive self-regulatory brain mechanisms.6 When mindful, pain is observed as and labeled a sensation. The term “sensation” carries a neutral valence compared to “pain” which may reflect greater alarm or threat to an individual. The mind is recognized to have a camera lens-like quality that can shift from zoom to wide angle. While pain can draw attention in a more narrow focus on the painful body area, when mindful, an individual can deliberately adopt a wide angle view, focusing on pain free areas and other neutral or positive states. In addition, when mindful, the unpleasant sensation rests in awareness not characterized by fear and distress, but by stability, compassion and curiosity. Patients may not have control over the onset of pain, but with mindfulness training, they can take control over their response to the pain. This deliberate adoption of mindful principles and practices can contribute to cognitive self-regulatory brain mechanisms that can ultimately impact pain perception.

I am excited to share additional research and practical clinical strategies that help patients self-regulate their reactions to pain and other symptoms in my 2019 courses, Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals at University Hospitals in Cleveland OH, April 6 and 7 and Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment in Houston TX, October 26 and 27 and Portland OR May 18 and 19. Hope to see you there!

1. Woo CW, Roy M, Buhle JT, Wager TD. Distinct brain systems mediate the effects of nociceptive input and self-regulation on pain. PLoS;2015;13(1):e1002036.

2. Baliki MN, Chialvo DR, Geha PY, Levy RM, et al. Chronic pain and the emotional brain: specific brain activity associated with spontaneous fluctuations of intensity of chronic back pain.J Neurosci. 2006;26(47):12165-73.

3. Hashmi JA, Baliki MN, Huang L, et al. Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain. 2013;136(pt9):2751-68.

4. Baliki MN, Peter B B, Torbey S, Herman KM, et al. Corticostriatal functional connectivity predicts transition to chronic back pain. Nat Neurosci.2012;15(8):1117-9.

5. D’Argembeau. On the role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in self-processing: The Valuation Hypothesis. Front Human Neurosci. 2013;7:372.

6. Zeidan F, Vago DR. Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief: a mechanistic account. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016 Jun;1373(1):114-27.

How does a male sports and orthopedic physical therapist come to teach about pelvic health and wellness? I was fortunate enough to spend ten years in the NHL as the physical therapist and athletic trainer for the Florida Panthers. Ice hockey is one of the sports that has the highest incidence of groin strains among other pelvic related pathologies.1 As a clinician that was responsible for taking care of the world’s best hockey players, I was challenged to understand the interconnected relationships between the lumbopelvic-hip complex very quickly.

In the early years of my career development and the treatment of mostly males with pelvic pathologies, I leaned heavily on pelvic health professionals to help me understand an area of the body I received little training on in school and even less in my clinical care as a sports and orthopedic manual physical therapist. After years of treating hip and pelvic pathologies on my players I became more comfortable in this enigmatic area of the body. A good friend of mine was on faculty with Herman & Wallace and we frequently would communicate and compare notes. She was treating an increasing number of “sports hernias” (now termed athletic pubalgia or core muscle injury) and was relying on me to help her understand this injury and how to treat it. In turn, she helped me understand what went on in the pelvic health profession and what those therapists were trained to treat and how they went about it.

In the early years of my career development and the treatment of mostly males with pelvic pathologies, I leaned heavily on pelvic health professionals to help me understand an area of the body I received little training on in school and even less in my clinical care as a sports and orthopedic manual physical therapist. After years of treating hip and pelvic pathologies on my players I became more comfortable in this enigmatic area of the body. A good friend of mine was on faculty with Herman & Wallace and we frequently would communicate and compare notes. She was treating an increasing number of “sports hernias” (now termed athletic pubalgia or core muscle injury) and was relying on me to help her understand this injury and how to treat it. In turn, she helped me understand what went on in the pelvic health profession and what those therapists were trained to treat and how they went about it.

This collaboration eventually led to me joining Herman & Wallace and offering a sports and orthopedic perspective to pelvic floor consideration. I have attended Herman & Wallace’s Pelvic Floor courses to fully understand the training that a pelvic health therapist undergoes. Admittedly, I do not perform internal work because I have found a niche helping clinicians such as myself who understand that the pelvic floor is a key variable in human movement and we need to understand it at a much higher level than what we are exposed to in school, but don’t have the career trajectory of becoming an internal practitioner of the pelvic floor.

I have designed the Athletes and Pelvic Rehabilitation course to reach both the sports and orthopedic clinician as well as the pelvic health practitioner who might be a veteran of pelvic floor education and treatment. Both groups will leave this course with additional tools for their clinical tool box in the realms of manual therapy and exercise.2 Here are some of the objectives for the course:

- Provide clinicians that do not perform internal work a better and more complete understanding of how the pelvic floor integrates into human movement, particularly higher-level activities such as running, lifting and all types of sporting movements.

- Provide both the experienced and pelvic floor early learner with a comprehensive paradigm of exercise theory, development and progressions as well as how to provide non-internal manual therapy to influence the performance of the pelvic floor.

- Provide strategies for clinicians to determine when your patient would be better served with a referral to a pelvic health practitioner and what the current evidence is to support your decision.

- Create innovative and engaging therapeutic exercise programs (home exercise programs too!) for your patients directed at the pelvis with specific attention to upright and functional positioning.

What do people who have attended courses with Dr. Dischiavi have to say? Janna wrote the following email to Herman & Wallace about Steve's Course:

"Good morning. I wanted to make sure that you knew what a fantastic clinician you have to join your team in Steve Dischiavi. I am a practicing OB and orthopedic therapist and felt this course was fantastic! Usually the main goal is to come away with a couple of clinical "pearls." I felt as though I came away with a full days worth of "pearls." I really liked that the course was not totally pelvic floor based, however was totally relevant to the women's health population, but it will also apply to the majority of my current patient population as well. Thank you for the opportunity to learn from Steve!"

1. Orchard JW. Men at higher risk of groin injuries in elite team sports: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(12):798-802.

2. Tuttle L. The Role of the Obturator Internus Muscle in Pelvic Floor Function. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2016;40(1):15-19.

In the spring of 2019, myself and two lab assistants will have the privilege of teaching PF1 to Kenyan physical therapists through the Kenya Medical Training College (KMTC) in Nairobi, Kenya. The program at KMTC started six years ago by Washington DC-based physical therapist Richard Jackson, and The Jackson Clinics Foundation (Teachandtreat.org), with a focus on orthopedic manual therapy. A neuro rehab program ensued two years later, and the aim for this women’s health program is to build a three level course series similar to the way it is taught in the United States. The goal of all of these programs is to transition them to Kenyan faculty within six years, which has recently occurred in the orthopedic component. Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehab Institute has graciously agreed to donate curriculum content to the women’s health course component.

Teaching assistant Terri Lannigan, PT, DPT, OCS, who has taught the lumbopelvic girdle course in the orthopedic program, and also practices women’s health physical therapy in the US, began laying the groundwork for this program with her students and in the Nairobi community last December. “Not only is there a tremendous need, but there is a lot of excitement from a group of students currently taking courses in the program, that women’s health education is coming to KMTC!”

Teaching assistant Terri Lannigan, PT, DPT, OCS, who has taught the lumbopelvic girdle course in the orthopedic program, and also practices women’s health physical therapy in the US, began laying the groundwork for this program with her students and in the Nairobi community last December. “Not only is there a tremendous need, but there is a lot of excitement from a group of students currently taking courses in the program, that women’s health education is coming to KMTC!”

Over the past month, I have been editing the Pelvic Floor 1 course to tailor it to our Kenyan physical therapist audience. The overwhelming majority of Kenyan PT’s do not have access to biofeedback or electric stim, so those sections will be omitted. As there are no documentation or coding requirements in the Kenyan health system, those sections of curriculum will also be edited out. Many of Terri’s PT students complained of significant underemployment, so we will keep the marketing component in our lectures, in hopes to promote expansion of women’s health PT to a larger segment of the Kenyan population.

Meanwhile, teaching assistant Kathy Golic, PT of Overlake Hospital Medical Center’s Pelvic Health Program in Bellevue, WA has headed up the data collection for a lecture on managing fistula and obstetric trauma. Kathy has accumulated data from many sources and conferred with several PTs currently involved in both clinical education as well as direct patient care in multiple African nations, to help us to create relevant, meaningful and culturally appropriate curriculum for this section of the PF1 course.

Pelvic Floor Level 1 will be offered between March 25 – April 6, 2019 at Kenya Medical Training College. We will post photos and additional information of our class and our experiences. We are grateful to Herman and Wallace and The Jackson Clinics Foundation for allowing us to be involved in this exciting endeavor.

Dustienne Miller MSPT, WCS, CYT is a Herman & Wallace faculty member, owner of Your Pace Yoga, and the author of the course Yoga for Pelvic Pain. Join her in Columbus, OH this April 27-28, to learn how yoga can be used to treat interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, vulvar pain, coccydynia, hip pain, and pudendal neuralgia. The course is also coming to Manchester, NH September 7-8, 2019, and Buffalo, NY on October 5-6, 2019.

How does a yoga program compare to a strength and stretching program for women with urinary incontinence? Dr. Allison Huang1 et al have published another research study, after publishing a pilot study2 on using group-based yoga programs to decrease urinary incontinence. Well-known yoga teachers Judith Hanson Lasater, PhD, and Leslie Howard created the yoga class and home program structure for this research study and the 2014 pilot study. The yoga program was primarily based on Iyengar yoga, which uses props to modify postures, a slower tempo to increase mindfulness, and pays special attention to alignment.

To be chosen for this study, women had to be able to walk more than 2 blocks, transfer from supine to standing independently, be at least 50 years of age, and experience stress, urge, or mixed urinary incontinence at least once daily. Participants had to be new to yoga and holding off on clinical treatment for urinary incontinence, including pelvic health occupational and physical therapy.

To be chosen for this study, women had to be able to walk more than 2 blocks, transfer from supine to standing independently, be at least 50 years of age, and experience stress, urge, or mixed urinary incontinence at least once daily. Participants had to be new to yoga and holding off on clinical treatment for urinary incontinence, including pelvic health occupational and physical therapy.

28 women were assigned to the yoga intervention group and 28 women were assigned to the control group. The mean age was 65.4 with the age range of 55-83 years of age.

The control group received bi-weekly group class and home program instruction on stretching and strengthening without pelvic floor muscle cuing or relaxation training.

The yoga program met for group class twice a week for 90 minutes each and practiced at home one hour per week. The control group met twice a week for 90 minutes with a one-hour home program every week. Both groups met for 12 weeks.

Both groups received bladder behavioral retraining informational handouts. The information sheets contained education about urinary incontinence, pelvic floor muscle strengthening exercises, urge suppression strategies, and instructions on timed voiding.

The yoga program included 15 yoga postures: Parsvokonasana (side angle pose), Parsvottasana (intense side stretch pose), Tadasana (mountain pose) Trikonasana (triangle pose), Utkatasana (chair pose), Virabhadrasana 2 (warrior 2 pose), Baddha Konasana (bounded angle pose), Bharadvajasana (seated twist pose), Malasana (squat pose), Salamba Set Bandhasana (supported bridge pose), Supta Baddha Konasana (reclined cobbler’s pose), Supta Padagushthasana (reclined big toe pose), Savasana (corpse pose), Viparita Karani Variation (legs up the wall pose), and Salabhasana (locust pose).

Women in the yoga intervention group reported more than 76% average improvement in total incontinence frequency over the 3-month period. Women in the muscle stretching/strengthening (without pelvic floor muscle cuing and relaxation training) control group reported more than 56% reduction in leakage episodes.

Stress urinary incontinence episodes decreased by an average of 61% in the yoga group and 35% in the control group (P = .045). Episodes of urge incontinence decreased by an average of 30% in the yoga group and 17% in the control group (P = .77).

The take away? We know behavioral techniques have been shown to improve quality of life and decrease frequency and severity of urinary incontinence episodes.3 Couple this with our clinical interventions, and our patients have a way to reinforce the work we do in the clinic by themselves, or socially within their community. Yoga can be another tool in the toolbox for optimizing pelvic health.

1) Diokno AC et al. (2018). Effect of Group-Administered Behavioral Treatment on Urinary Incontinence in Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med.1;178(10):1333-1341. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3766.

2) Huang, Alison J. et al. (2019). A group-based yoga program for urinary incontinence in ambulatory women: feasibility, tolerability, and change in incontinence frequency over 3 months in a single-center randomized trial. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 220(1) 87.e1 - 87.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.031

3) Huang, A. J., Jenny, H. E., Chesney, M. A., Schembri, M., & Subak, L. L. (2014). A group-based yoga therapy intervention for urinary incontinence in women: a pilot randomized trial. Female pelvic medicine & reconstructive surgery, 20(3), 147-54.

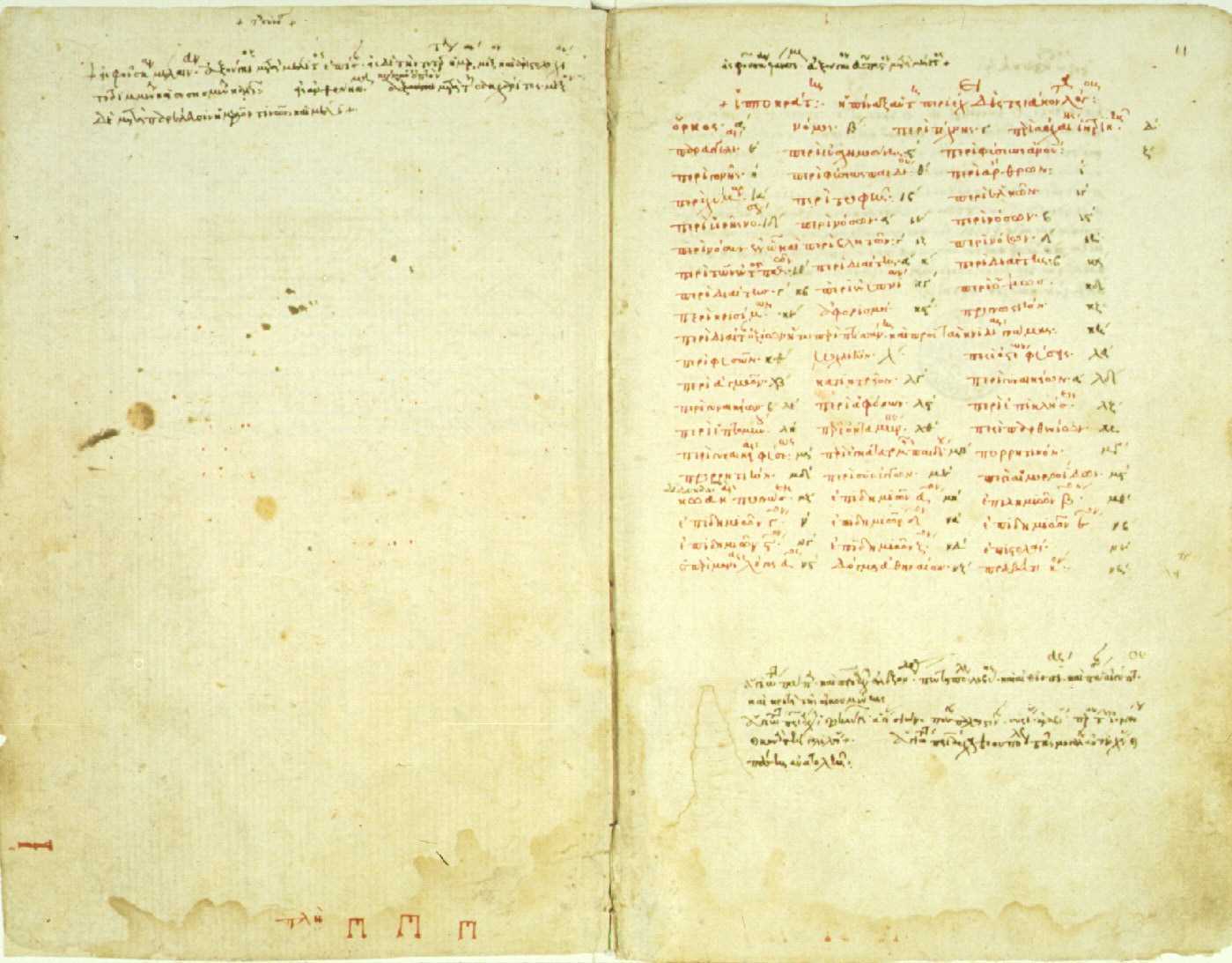

The need for artful incorporation of Hippocrates’ wisdom is great in today’s healthcare landscape. As conversation of nutrition broadens into multidisciplinary fields, his wisdom resonates: first, “we must make a habit of two things; to help; or at least to do no harm”. Second, we must modernize the ancient adage: “let food be thy medicine and let medicine be thy food”. And finally, health care providers will do well to be guided by his insight that “all disease starts in the gut”. Hippocrates’ keen observations during his era, modern science is confirming, hold keys to the plight of our times as we seek to find better ways to manage complex conditions commonly encountered in pelvic rehab practice settings and beyond.

Considered some of the oldest writings on medicine, the “Hippocratic Corpus” is a collection of more than 60 medical books attributed directly and indirectly to Hippocrates himself who lived from approximately 460 to 377 BCE.2 According to the Corpus, Hippocratic approach recommends physical exercise and a “healthy diet” as a remedy for most ailments - with plants being prized for their healing properties. If -during illness states - employment of nourishment and movement strategies fail, then medicinal considerations could be made. This logos - the ancient Greek word for logic - is the art of reason whose relevance today is perhaps more poignant than in ancient times.

Considered some of the oldest writings on medicine, the “Hippocratic Corpus” is a collection of more than 60 medical books attributed directly and indirectly to Hippocrates himself who lived from approximately 460 to 377 BCE.2 According to the Corpus, Hippocratic approach recommends physical exercise and a “healthy diet” as a remedy for most ailments - with plants being prized for their healing properties. If -during illness states - employment of nourishment and movement strategies fail, then medicinal considerations could be made. This logos - the ancient Greek word for logic - is the art of reason whose relevance today is perhaps more poignant than in ancient times.

In this logos, by making a habit of helping, or at the very least, not harming, it becomes particularly important to identify the unique nutritional landscape that surrounds us. The Hippocratic Oath emanates reason. It is logical that we would seek to practice (healthcare) to the best of our ability, share knowledge with other providers, employ sympathy, compassion and understanding, and help in disease prevention whenever possible.2 One of the most helpful and powerful aspects of rehabilitation is the gift of time we have for meaningful and instructional conversation with our clients. Our interactions with clients can and should address the realm of nutrition as it relates to the health of the mind and body. Because, after all - to help - is why many become health care providers in the first place.

Detailing a “healthy diet” in Hippocratic times was certainly simpler, as the uncontrolled variable of processed foods- as we know them- did not exist. Therefore, we reflect upon the quote: “let food be thy medicine and let medicine be thy food” and acknowledge that this modern food landscape is vastly different 1 than in ancient times. Compounding the issue, our standard logic for helping has gotten somewhat out of order. And both medicine and food carry meanings today reflective of modern times. The issues of poly-pharmacy and the tragedy of medically prescribed unintentional overdoses (or intolerances) remind us of our ‘medicine first’ mentality and the unfortunate reality that medicine is not the cure-all we so wish it could be. Further, not all ‘food’ today is food. Real food sustains and nourishes us. Real food can also heal. We need to celebrate real food for being real food, and champion it’s miraculous ability to support, heal, and transform the human condition.

Finally, health care providers will do well to be guided by Hippocratic insight that “all disease starts in the gut” and to logically extrapolate the opposite: much healing can begin in the gut. It is through this ancient concept that we can organize our modern science and begin to concretely and intentionally help heal ourselves and others from the inside out. Once we understand the key role of digestion and our gut on our health and well-being, the rest is pure logic. We simply need a map for navigation of these universal concepts to go along with our renewed appreciation for the art of reason.

Let Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist help provide this map. Evolve your nutritional logos into a beautiful and nourishing framework by joining the hundreds of pelvic rehab therapists and other health care providers who have attended Nutrition Perspectives in Pelvic Rehab. Be inspired and empowered on your integrative journey. Live courses will be offered at three sites in 2019: March 1-3 in Arlington, VA, June 7-9 in Houston, TX, and October 11-13 in Tampa, FL!

Fardet, A., Rock, E., Bassama, J., Bohuon, P., Prabhasankar, P., Monteiro, C., . . . Achir, N. (2015). Current food classifications in epidemiological studies do not enable solid nutritional recommendations for preventing diet-related chronic diseases: the impact of food processing. Adv Nutr, 6(6), 629-638. doi:10.3945/an.115.008789

Biography.com https://www.biography.com/people/hippocrates-082216. Accessed January 11, 2019.

When It Comes to Bone Building Activities for Osteoporosis, there’s Weight Bearing and then there’s Weight Bearing!

Ask just about anyone on the street what one should do for osteoporosis and the typical answer is- weight bearing exercises. And they would be partially right. Weight bearing, or loading activities have been shown to increase bone density.1 But that’s not the whole story.

Regarding weight bearing exercises, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture? We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their own body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

Regarding weight bearing exercises, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture? We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their own body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

An alternative is to focus on “odd impact” loading. A study by Nikander et al 2 targeted female athletes in a variety of sports classified by the type of loading they apparently produce at the hip region; that is, high-impact loading (volleyball, hurdling), odd-impact loading (squash-playing, soccer, speed-skating, step aerobics), high magnitude loading (weightlifting), low-impact loading (orienteering, cross-country skiing), and non-impact loading (swimming, cycling). The results showed high-impact and odd-impact loading sports were associated with the highest bone mineral density.

Morques et al, in Exercise Effects on Bone Mineral Density in Older Adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, found that odd impact has potential for preserving bone mass density as does high impact in older women. Activities such as side stepping, figure eights, backward walking, and walking in square patterns help “surprise the bones” due to different angles of muscular pull on the hip. The benefit, according to Nikander, is that we can get the same osteogenic benefits with less force; moderate versus high impact. This type of bone training would offer a feasible basis for targeted exercise-based prevention of hip fragility. I tell my osteoporosis patients that if they walk or run the same route, the same distance, and the same speed that they are not maximizing the osteogenic benefits of weight bearing. Providing variety to the bones creates increased bone mass in the femoral neck and lumbar spine.4

Dancing is another great activity which combines forward, side, backward, and diagonal motions to movement. In addition, it adds music to make the “weight bearing exercises” more fun. Due to balance and fall risk many senior exercise classes offer Chair exercise to music. Unfortunately sitting is the most compressive position for the spine and is particularly problematic with osteoporosis patients. Also the hips do not get any weight bearing benefit. Whenever safely possible, have patients stand; you can position two kitchen chairs on either side, much like parallel bars, to hold on to while they “dance.”

Providing creativity in weight bearing activities using odd impact allows not only for fun and stimulation; it also offers more “bang for the buck!”

- Mosekilde L. Age-related changes in bone mass, structure, and strength--effects of loading. Z Rheumatol (2000); 59 Suppl 1:1-9.

- Nikander et al. Targeted exercises against hip fragility. Osteoporosis International (2009)

- Marques et al. Exercise effects on bone mineral density in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Epub 2011 Sep 16

- Weidauer L. et al. Odd-impact loading results in increased cortical area and moments of inertia in collegiate athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol (2014)

Andrea Wood, PT, DPT, WCS, PRPC is a pelvic health specialist at the University of Miami downtown location. She is a board certified women’s health clinical specialist (WCS) and a certified pelvic rehabilitation practitioner (PRPC). She is passionate about orthopedics and pelvic health. In her spare time, you can find her enjoying the south Florida outdoors.

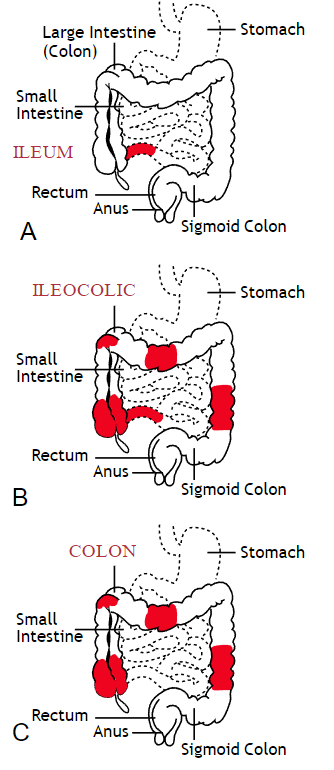

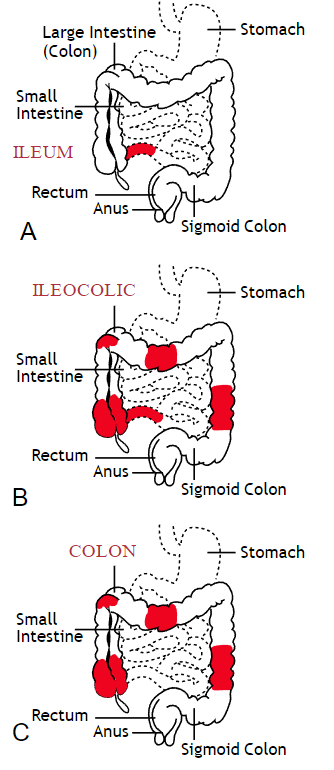

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes the two diagnosis of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. While both can cause similar health effects, the differences of the disease pathologies are listed below:1

| Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn’s Disease | |

| Affected Area |

|

|

| Pattern of Damage |

|

|

Common complications experienced by patients with IBD include fecal incontinence, fecal urgency, night time soiling, urinary incontinence, abdominal pain, hip and core weakness, pelvic pain, fatigue, osteoporosis, and sarcopenia. In a sample of 1,092 patients with Crohn’s Disease, Ulcerative Colitis, or unclassified IBD, 57% reported fecal incontinence. Fecal incontinence was reported not only during periods of flare ups, but also during remission periods.2 One common factor affecting fecal incontinence is external anal sphincter fatigue. External anal sphincter fatigue has also been shown to be present in IBD patients who are not experiencing fecal incontinence or fecal urgency. IBD patients have been shown in studies to have similar baseline pressures versus healthy matched controls, thus indicating the possibility that deficits in endurance versus strength can play a larger role in fecal incontinence.3 Other factors contributing to fecal incontinence include post inflammatory changes that may alter anorectal sensitivity, anorectal compliance, neuromuscular coordination, and cause visceral hypersensitivity. Visceral hypersensitivity may be caused by continuous release of inflammatory mediators found in patients with IBD. It is also important to screen properly for incomplete bowel emptying and stool consistency to rule out overflow diarrhea or fecal impaction. Reports of need to splint digitally for full evacuation may indicate incomplete bowel emptying and defaectory disorders such as paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis muscle or rectocele. Anorectal manometry testing may be highly useful in identifying patients likely to improve from biofeedback therapy.4

Urinary incontinence can also be another secondary consequence to IBD. In a sample of 4,827 patients with IBD, 1/3 of responders reported urinary incontinence that was strongly associated with the presence of fecal incontinence. Frequent toilet visits for defecation may stimulate overactive bladder. Women were more likely to experience fecal incontinence versus men. One possible mechanism for increased fecal incontinence in women is men often have a longer and more complete anal sphincter that may be protective of fecal incontinence.5

Physical activity has been shown to be lower in patients with IBD versus healthy controls. 6, 7 Guiding IBD patients in proper exercises programs can have great benefits. Exercise may reduce inflammation in the gut and maintain the integrity of the intestines, reducing inflammatory bowel disease risk.8 It can also help increase bone mass density, an important factor in IBD patients who are at greater risk for osteoporosis. It has also been shown to help general fatigue in IBD patients. Patients with Crohn’s disease who participate in higher exercise levels may be less likely to develop active disease at 6 months. Treadmill training at 60% VO2 max and running three times a week has not been shown to evoke gastrointestinal symptoms in IBD patients. An increase of BMI predicts poorer outcomes and shorter time to first surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease.6

Conservative physical therapy interventions for treating IBD symptoms can include the following:

| Symptoms resulting from IBD | Physical Therapy Interventions |

| Fecal Incontinence (FI) |

|

| Urinary urgency |

|

| Sarcopenia |

|

| Fatigue |

|

| Pelvic Pain |

|

Surgical interventions for IBD are dependent upon what type of disease the patient has and what areas of the intestines are affected the most. Surgery may be considered once the disease has become non responsive to medication therapy and quality of life continues to decline. A colectomy involves removing the colon while a proctocolectomy involves both removal of the colon and rectum. For ulcerative colitis patients, options include total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy or a restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Restorative proctocolectomy eliminates the need for an ostomy bag making it the preferred surgery of choice if possible and gold standard for ulcerative colitis patients.10 For patients with Crohn’s disease, options include resection of part of the intestines followed by an anastomosis of the remaining healthy ends of the intestines, widening of the narrowed intestine in a procedure called a strictureplasty, colectomy or proctocolectomy, fistula repair, and removal of abscesses if needed.11

1. Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. 2019. What is Crohn’s Disease. Retrieved from: http://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-are-crohns-and-colitis/what-is-crohns-disease/

2. Vollebregt PF, van Bodegraven A, Markus-de Kwaadsteniet T, et al. Impacts on perianal disease and faecal incontinence on quality of life and employment in 1092 patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2018; 47: 1253-1260

3. Athanasios A, Kostantinos H, Tatsioni A et al. Increased fatigability of external anal sphincter in inflammatory bowel disease: significance in fecal urgency and incontinence. J Crohns Colitis (2010) 4: 553-560.

4. Nigam G, Limdi J, Vasant D. Current perspectives on the diagnosis and management of functional anorectal disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018 Dec 6: doi: 10.1177/1756284818816956

5. Norton C, Dibley L, Basset P. Faecal incontinence in inflammatory bowel disease: Associations and effect on quality of life. J Crohn’s Colitis. (2013) 7, e302-e311.

6. Biliski J, Mazur-Bialy A, Brzozowski B et al. Can exercise affect the course of inflammatory bowel disease? Experimental and clinical evidence. Pharmacological Reports. 2016 (68): 827-836.

7. Tew G, Jones K, Mikocka-Walus A. Physical activity habits, limitations, and preditors in people with inflammatory bowel disease: a large cross-sectional online survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016; 22(12): 2933-2942.

8. Vincenzo M, Villano I, Messina A. Exercise modifies the gut microbiota with positive health effects. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevitiy. 2017: Article ID 3831972.

9. Cramer H, Schafer M, Schols M. Randomised clinical trial: yoga vs written self care advice for ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 45: 1379-1389.

10. Cornish J, Wooding K, Tan E, et al. Study of sexual, urinary, and fecal function in females following restorative proctocolectomy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 18 (9) 2012. 1601-160

11. Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. 2019. Surgery Options. Retrieved from: http://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-are-crohns-and-colitis/what-is-crohns-disease/surgery-options.html