Most people are told that inguinal hernia repair is a low risk surgery. While death or severe injury is rare, penile or testes pain after hernia repair is not a novel or recent finding. In 1943, Magee first discussed patients having genitofemoral neuralgia after appendix surgery. By 1945, both Magee and Lyons stated that surgical neurolysis gave relief of genital pain following surgical injury (neurolysis is a surgical cutting of the nerve to stop all function). However, it should be noted that with neurolysis, sensory loss will also occur, which is an undesired symptom for sexual function and pleasure. In 1978 Sunderland stated genitofemoral neuralgia was a well-documented chronic condition after inguinal hernia repair.

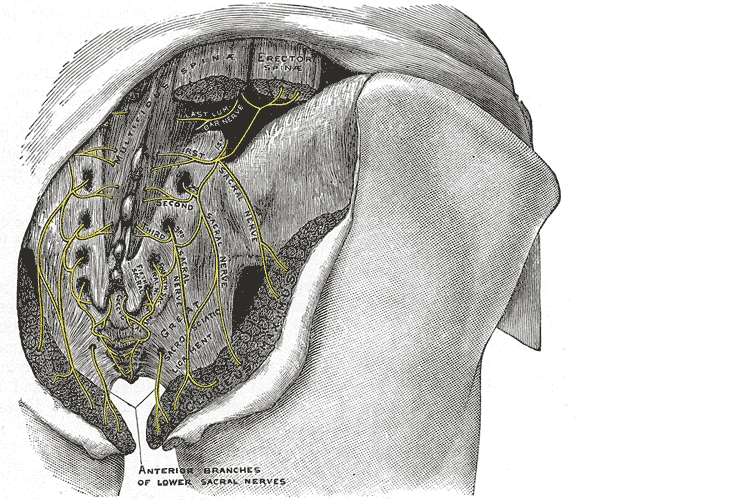

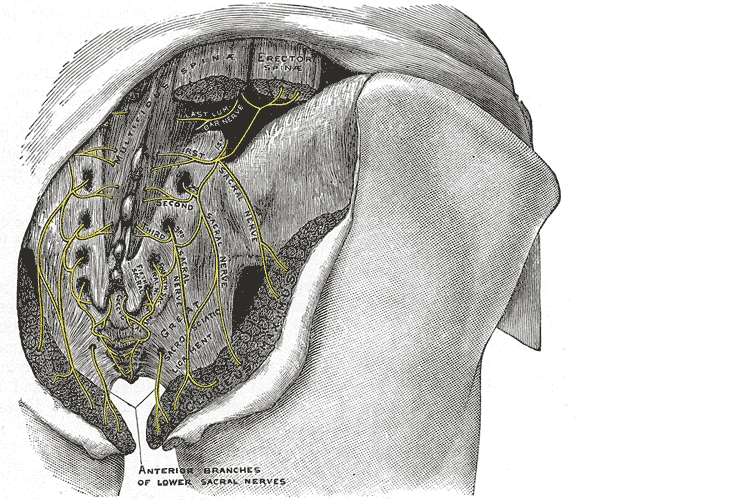

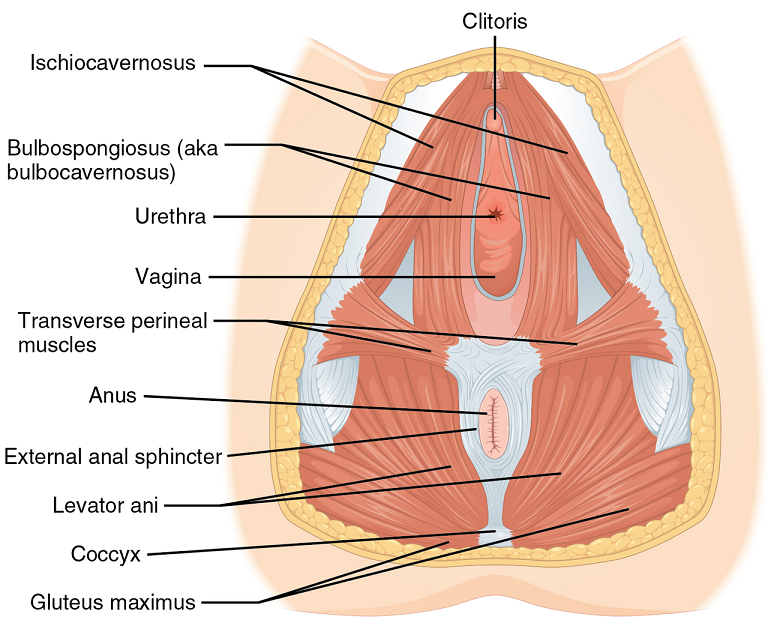

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

In 1999 Stark et al noted pain reports as high as 63% post hernia repair. The highest rates of genitofemoral neuralgia are reported with laparoscopic or open hernia repair (Pencina, 2001). The mechanism for GF neural entrapment is entrapment within scar or fibrous adhesions and parasthesia along the genitofemoral nerve (Harms 1984, Starling and Harms 1989, Murovic 2005, and Ducic 2008). It is well known that scar and adhesion densify and visceral adhesions increase for years after surgery. Thus, symptoms can increase long after the surgery or may take years to develop. In 2006, Brara postulated that mesh in the region can contribute to subsequent genitofemoral nerve tethering which can be exacerbated by mesh in the inguinal or the retroperitoneal space. With an anterior mesh placement, there is no fascial protection left for the genitofemoral nerve.

Genitofemoral neuralgia is predominately reported as a result of iatrogenic nerve damage during surgery or trauma to the inguinal and femoral regions (Murovic et al, 2005). However, genitofemoral neuropathy can be difficulty and elusive to diagnose due to overlap with other inguinal nerves (Harms, 1984 and Chen 2011).

In my clinical experience, I have seen such symptoms after hernia repair, but also after procedures near the inguinal region such as femoral catheters for heart procedures, appendectomies, and occasionally after vasectomy.

As a pelvic PT, what are we to do with this information? First off, we can realize that all pelvic neuropathy is not necessarily due to the pudendal nerve. In the anterior pelvis, there is dual innervation from the inguinal nerves off the lumbar plexus as well as the dorsal branch of the pudendal nerve. When patients have a history of inguinal hernia repair, we can consider the genitofemoral nerve as a source of pain. Medicinally, the only research validated options for treatment are meds such as Lyrica or Gabapentin that come with drowsiness, dizziness and a score of side effects. Surgically neurectomy or neural ablation are options with numbness resulting, however, many patients do not want repeated surgery or numbness of the genitals. As pelvic therapists, we can manually fascially clear the path of the nerve from L1/L2, through the psoas, into and out of the canal and into the genitals. We can also manually directly mobilize the nerve at key points of contact as well as doing pain free sliders and gliders and then give the patient a home program to maintain mobility. Pelvic manual therapy can offer a low risk, side-effect free option to ameliorate the sequella of inguinal hernia repair. Come join us at Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment in Chicago this Spring to learn how to effectively treat all the nerves of the lumbar plexus.

Cesmebasi, A., Yadav, A., Gielecki, J., Tubbs, R. S., & Loukas, M. (2015). Genitofemoral neuralgia: a review. Clinical Anatomy, 28(1), 128-135.

Lyon, E. K. (1945). Genitofemoral causalgia. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 53(3), 213.

Magee, R. K. (1943). Genitofemoral Causalgia: New Syndrome. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 98(3), 311.

Sunderland S. Nerves and nerve injuries. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1978

Today's guest post comes from Kelsea Cannon, PT, DPT, a pelvic health practitioner in Seattle, WA. Kelsea graduated from Des Moines University in 2010 and practices at Elizabeth Rogers Pilates and Physical Therapy.

Many studies done on pelvic floor muscle training largely have subjects who are Caucasian, moderately well educated, and receive one-on-one individualized care with consistent interventions. This led a group of researchers to investigate the occurrence of pelvic floor dysfunction, specifically pelvic organ prolapse (POP), in parous Nepali women. These women are known to have high incidences of POP and associated symptomology. Another impetus to perform this research: the discovery that there was a major lack of proper pelvic floor education for postpartum women. These women were commonly encouraged to engage their pelvic floor muscles via performing supine double leg lifts, sucking in their tummies/holding their breath/counting to ten, and squeezing their glutes. These exercises would be on a list of no-no’s here in the United States. In 2017, Delena Caagbay and her team of researchers discovered that in Nepal, no one really knew the correct way to teach proper pelvic floor muscle contractions, preventing the opportunity for women to better understand their pelvic floors. The team then set out to investigate the needs of this population, with the eventual goal of providing effective pelvic floor education for Nepali women.

Caagbay and her team first wanted to know what baseline muscle activity the Nepali women had in their pelvic girdle. Physical examinations and internal pelvic floor muscle strength assessments revealed that surprisingly there was a low prevalence of pelvic floor muscle defects, such as levator avulsions and anal sphincter trauma. Uterine prolapses were most common while rectoceles were comparatively less common. Their muscles were also strong and well-functioning, often averaging a 3/5 on the Modified Oxford Scale. It was hypothesized that these women had low prevalence of muscle injury because instruments were not commonly used during childbirth, they had lower birth weight babies, and the women were typically younger when giving birth (closer to 20-21 years old). But they had a high prevalence of POP even with good muscle tone? Researchers suggested that their incidence of POP is likely stemming from their sociocultural lifestyle requirements, as women are left to do most of the daily household chores and caregiving tasks while men often travelled away from the home to perform paid labor. Physical responsibilities for these women commonly begin at younger ages and while it helps promote good muscle tone, the heavier loading places pressure on the connective tissue and fascia that support the pelvic organs. Because of the demands of their lifestyles, Nepali women are often forced to return to their physically active state within a couple weeks after giving birth.

Caagbay and her team first wanted to know what baseline muscle activity the Nepali women had in their pelvic girdle. Physical examinations and internal pelvic floor muscle strength assessments revealed that surprisingly there was a low prevalence of pelvic floor muscle defects, such as levator avulsions and anal sphincter trauma. Uterine prolapses were most common while rectoceles were comparatively less common. Their muscles were also strong and well-functioning, often averaging a 3/5 on the Modified Oxford Scale. It was hypothesized that these women had low prevalence of muscle injury because instruments were not commonly used during childbirth, they had lower birth weight babies, and the women were typically younger when giving birth (closer to 20-21 years old). But they had a high prevalence of POP even with good muscle tone? Researchers suggested that their incidence of POP is likely stemming from their sociocultural lifestyle requirements, as women are left to do most of the daily household chores and caregiving tasks while men often travelled away from the home to perform paid labor. Physical responsibilities for these women commonly begin at younger ages and while it helps promote good muscle tone, the heavier loading places pressure on the connective tissue and fascia that support the pelvic organs. Because of the demands of their lifestyles, Nepali women are often forced to return to their physically active state within a couple weeks after giving birth.

After assessing the current needs, cultural norms, and prevalence of POP in Nepali women, Caagbay et al created an illustrative pamphlet on how to contract pelvic floor muscles as well as provided verbal instruction on pelvic floor muscle activation. Transabdominal real time ultrasound was applied to assess the muscle contraction of 15 women after they received this education. Unfortunately, even after being taught how to engage their pelvic floor muscles, only 4 of 15 correctly contracted their pelvic floors.

This study highlighted that brief verbal instruction plus an illustrative pamphlet was not sufficient in teaching Nepali women how to correctly contract their pelvic floor muscles. Although there was a small sample size, these results can likely be extrapolated to the larger population. Further research is needed to determine how to effectively teach correct pelvic floor muscle awareness to women with low literacy and/or who reside in resource limited areas. Lastly, it is important to consider the significance of fascial and connective tissue integrity within the pelvic floor when addressing pelvic organ prolapse.

1 Can a leaflet with brief verbal instruction teach Napali women how to correctly contract their pelvic floor muscles? DM Caagbay, K Black, G Dangal, C Rayes-Greenow. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council 15 (2), 105-109.

https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/JNHRC/article/viewFile/18160/14771

2 Pelvic Health Podcast. Lori Forner. Pelvic organ prolapse in Nepali women with Delena Caagbay. May 31, 2018.

3 The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse in a Nepali gynecology clinic. (2017) F. Turel, D. Caagbay, H.P. Dietz. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sydney Medical School Napean, University of Sydney.

4 The prevalence of major birth trauma in Nepali women. (2017) F. Turel, D. Caagbay, H.P. Dietz. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sydney Medical School Nepean, University of Sydney.

Faiq Shaikh, M.D. is a dual fellowship-trained nuclear medicine physician & Informaticist, with a focus on translational research in the domains of Cancer imaging, Radiomics, Genomics, Informatics and Machine learning applications in Medicine. He has written more than 35 scientific articles and abstracts and 3 book chapters on related topics.

Introduction

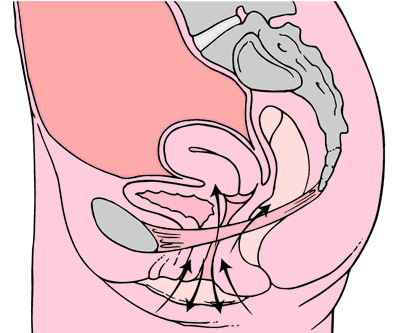

Pelvic floor weakening is a common (occuring in half of women 50+) condition that leads to descent of the urinary bladder, uterovaginal vault, and rectum in the females, leading to urinary and fecal incontinence, and in extreme cases, pelvic organ prolapse.

Causes

Pelvic floor weakness is caused by a variety of factors, most of which increase the intra-abdominal pressure, such as pregnancy, multiparity, advanced age, menopause, obesity, connective tissue disorders, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc. All these conditions lead to weakness of the pelvic musculature, ligaments, and fascia support result in descent of the pelvic floor organs.

Anatomy

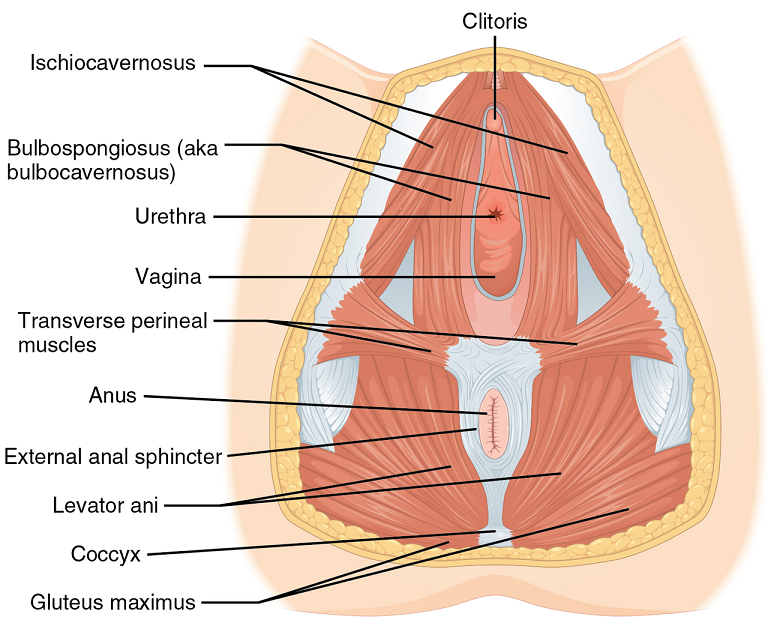

The pelvic floor is divided into three compartments:

- Anterior compartment: contains the urinary bladder and urethra

- Middle compartment: contains the uterus, cervix, and vagina

- Posterior compartment: contains the rectum.

The structures in these compartments are supported by muscles, fascia, and ligaments anchoring them to the bony pelvis.

The endopelvic fascia is the most superior layer and covers the levator ani muscles and the pelvic viscera. Laterally, it forms the arcus tendineus. It attaches the cervix and vagina to the pelvic side wall as the parametrium and paracolpium. Posteriorly, the endopelvic fascia forms the rectovaginal fascia between the posterior vaginal wall and the rectum.

These fascial condensations are not well visualized on conventional MRI but their defects may be seen indirectly through secondary findings. These ligaments are not visualized on conventional MRI but may be visualized with an endovaginal coil which allows higher resolution and signal-to-noise ratio.

The levator ani muscles lie deep in relation to the endopelvic fascia and comprise of the puborectalis and the iliococcygeus muscles. Posteriorly and in the midline, the iliococcygeus condenses to form the levator plate. These are all well visualized on MRI. The perineal membrane lies inferior to the levator ani muscles and separates the vagina and rectum, which may be damaged during vaginal delivery when episiotomy is performed.

Pathophysiology

Pelvic floor relaxation is the weakness of the supporting muscles, fascia, and ligaments. This weakness progresses with age and may be related to hypoestrogenic states, such as menopause.

- occurs when the urinary bladder prolapses into the anterior vaginal wall, which may cause urinary incontinence.

- occurs due to weakness of the rectovaginal fascia, prolapsing rectum into the posterior vaginal wall, which may cause fecal incontinence.

- The parametrium and paracolpium weakness causes prolapse of the cervix and uterus.

- occurs when the small bowel prolapses through the rectovaginal fascia.

Accurate assessment of all compartments of the pelvic floor is necessary for surgical planning in order to minimize the risk of recurrence.

Diagnostics

Methods for the assessment of pelvic floor weakness include urodynamics, voiding cystourethrography, ultrasonography of the bladder neck and anal sphincter, fluoroscopic cystocolpodefecography, and MRI - which m is now the standard-of-care for preoperative planning for pelvic floor dysfunction, although it’s still not used for routine assessment.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI visualizes all three compartments of the pelvic floor and the pelvic support muscles and organs. We perform dynamic MRI of the pelvic floor with the patient in the supine or lateral decubitus positions. Conversely, MRI defecography or fluoroscopic cystocolpodefecography are performed in the sitting position, which is closer to the physiologic state. MR defecography is not superior to dynamic supine MRI for depiction of clinically relevant bladder descent and rectoceles. Overall, MRI accurately detects enteroceles and its contents when compared with fluoroscopic cystodefecography.

The preferred MRI pelvis protocols include: Ultrafast, large-field-of-view, T2-weighted sequences such as single-shot fast spin-echo (SSFSE), and half-Fourier acquisition turbo spin-echo (HASTE). After the dynamic examination is completed, small-field-of-view (20–24 cm) T2-weighted axial fast spin-echo (FSE) or axial turbo spin-echo (TSE) sequences are acquired to obtain high-resolution images of the muscles and fascia of the pelvic floor. The entire examination is typically completed in 20 minutes. This exam is performed with a torso phased-array coil wrapped around the pelvis. Endovaginal coil may be used to improve the spatial resolution of the pelvic ligaments, but it is invasive and can be uncomfortable.

MRI visualizes the uterus, cervix, and rectovaginal space. Ultrasonic gel may be administered into the vagina and rectum for better visualization. Also, incompletely voiding the urinary bladder improves visualization of the bladder and anterior vaginal wall prolapse.

For patients with a rectocele, patient is imaged after having evacuated the rectal contents. Chronic constipation and perineal hernias show as ballooning of the iliococcygeus muscle. The level of the pelvic floor is demarcated radiologically on the midsagittal image using the pubococcygeal line (from the most inferior portion of the pubic symphysis to the last horizontal sacrococcygeal joint). The levator plate should be parallel to the pubococcygeal line in normal cases.

The H line (5 cm) extends from the inferior symphysis pubis to the posterior anorectal junction on the midsagittal image and depicts the levator hiatus. The M line (2 cm) goes perpendicular from the pubococcygeal line to the most distal aspect of the H line and depicts the descent of the levator hiatus from the pubococcygeal line. Pelvic floor prolapse causes sloping of the levator plate and increasing length of the H and M lines, indicating widening and descent of the levator hiatus.

The T2-weighted axial images of the pelvic floor should be analyzed for signal intensity, symmetry, thickness, and fraying of the pelvic floor muscles. Bladder neck at strain should be less than 1 cm away from the pubococcygeal line. Descent of the bladder neck below the pubococcygeal line depicts the prolapse of the urinary bladder through the anterior vaginal wall resulting in a cystocele. Descent of the bladder neck during strain results in clockwise rotational descent of the bladder neck and proximal urethra. Distortion of the periurethral and paraurethral ligaments is seen in stress urinary incontinence. The normal butterfly shape of the vagina may also be altered by weakening of the paravaginal ligaments as it is displaced posteriorly. Prolapse of the middle compartment is associated with the vaginal apical prolapse and damage to the paracolpium seen in post-hysterectomy patients. On midsagittal MR images, descent of the uterus, cervix and vagina usually suggests disruption of the uterosacral or cardinal ligaments and elongated H and M lines. Pelvic organ prolapse increases the urogenital hiatus in the levator muscles. Caudal angle of more than 10° between the levator plate and the pubococcygeal line on midsagittal image is a sign of pelvic floor weakness.

On the midsagittal image, rectocele is identified by a rectal bulge of more than 3 cm (from anal canal and the tip of the rectocele). Contrast-enhanced MR shows hyperintense T2 signal in peritoneal fat contents in peritoneoceles, the hyperintense fluid-filled small-bowel loops in enteroceles, and the hyperintense gel-filled rectum/sigmoid colon in rectoceles/sigmoidoceles. Intussusception of the rectum on MR is seen as rectum invaginating distally toward the anal canal (MR defecography is superior to dynamic supine MR for this indication).

Performing MRI for pelvic floor dysfunction when indicated for surgical planning and the assessment if the extent of disease may reduce the risk of surgical failure.

This information is extremely useful to urogynecologists and surgeons.

MRI of pelvic floor dysfunction: review. Law YM, Fielding JR. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008.

In 1984, Mersheed Sinaki MD and Beth Mikkelsen, MD published a landmark article based on their research with osteoporotic women. (Yes, it was 1984 but this is one study no one would want to reproduce).1

The study follows 59 women with a diagnosis of postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis and back pain who were divided into 4 groups that included spinal Extension (E), Flexion (F), Combined (E+F), or No Therapeutic Exercises (N). Ages ranged from 49 to 60 years (mean, 56 years). Follow-up ranged from one to six years (mean for the groups, 1.4 to 2 years). All patients had follow-up spine x-rays before treatment and at follow-up, at which time any further wedging and compression fractures were recorded. Additional fractures occurred as follows:

The study follows 59 women with a diagnosis of postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis and back pain who were divided into 4 groups that included spinal Extension (E), Flexion (F), Combined (E+F), or No Therapeutic Exercises (N). Ages ranged from 49 to 60 years (mean, 56 years). Follow-up ranged from one to six years (mean for the groups, 1.4 to 2 years). All patients had follow-up spine x-rays before treatment and at follow-up, at which time any further wedging and compression fractures were recorded. Additional fractures occurred as follows:

Group E: 16%

Group F: 89%

Group E+F: 53%

Group N: 67%

This study suggests that a significantly higher number of vertebral compression fractures occur in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis who followed a flexion based exercise program, than those using extension exercises. It also indicated that patients who did no exercises were less likely to sustain a vertebral compression fracture than those doing flexion exercises.

Due to the anatomical nature of the thoracic spine, the vertebral bodies are placed into a normal kyphosis. The anterior portion of the thoracic spine carries an excess load which can predispose an individual to fracture. Combine the propensity of flexion based daily activities such as brushing teeth, driving, texting or typing, with the fact that vertebral bodies are primarily made up of trabecular (spongy) bone and you have a recipe for disaster.

In the US, studies suggest that approximately one in two women and one in four men age 50 and older will break a bone due to osteoporosis.2 Now picture the many individuals who think that the only way to strengthen their core is by doing sit ups or crunches, further compressing the anterior portion of the spine. Often these exercises are being taught or led by fitness instructors who unknowingly put their clients at risk. Only 20-30% of compression fractures are symptomatic.3 This means that individuals may continue performing crunches, sit-ups, or toe touches even after they have fractured. No one realizes it until the person may notice a loss in height (they have trouble reaching a formerly accessible shelf or trouble hanging up clothes,) or the fracture is seen on an x-ray for pneumonia, etc. The Dowager’s Hump (hyper-kyphosis) may begin to appear. Or the person sustains another fragility fracture; possibly a hip.

Note that the E Group (Extension) still sustained fractures but significantly less than the other three groups. This suggests that there is a protective effect in strengthening the back extensors which has led to an emphasis on Site Specific back strengthening exercises as well as correct weight bearing activities.

Telling osteoporosis patients that they should exercise without giving them specific guidelines (such as in the Meeks Method) is doing them a disservice. General exercise provides minimal to no benefit in building stronger bones and the wrong exercises could put them at great risk for fractures. Educating our referral sources for the need to recommend therapists trained in correct osteoporosis management and the difference between “right” and “wrong” exercises may be the first step in reducing fragility fractures.

1. Sinaki M, Mikkelsen BA. Postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis: flexion versus extension exercises. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1984 Oct; 65.

2. NOF.org. National Osteoporosis Foundation

3. McCarthy J, MD, Davis A, MD, Am Family Physician. Diagnosis and Management of Vertebral Compression Fractures

A recent article in the Washington Post Health & Science section explored the wonders of dietary fibre in an article called ‘Fiber has surprising anti-aging benefits, but most people don’t eat enough of it’ The article discussed how ‘…Fiber gets well-deserved credit for keeping the digestive system in good working order — but it does plenty more. In fact, it’s a major player in so many of your body’s systems that getting enough can actually help keep you youthful. Older people who ate fiber-rich diets were 80 percent more likely to live longer and stay healthier than those who didn’t, according to a recent study in the Journals of Gerontology’

But what is fiber and why does it matter?

Before we jump in there, let me answer the perennial questions that arise when we, as pelvic rehab clinicians, talk about fiber…’Is it in our scope of practice to talk about food?!’ I think it is fundamental that if we are placing ourselves as experts in bladder and bowel dysfunction, that we also remember that we can’t focus on problems at one end of ‘the tube’ without thinking about what happens at the other end. Furthermore, let me quote the APTA RC 12-15: The Role of the Physical Therapist in Diet and Nutrition. (June 2015): “as diet and nutrition are key components of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of many conditions managed by physical therapists, it is the role of the physical therapist to evaluate for and provide information on diet and nutritional issues to patient, clients, and the community within the scope of physical therapist practice. This includes appropriate referrals to nutrition and dietary medical professionals when the required advice and education lie outside the education level of the physical therapist’’

Fiber plays a huge role in so many of the health issues that we as clinicians face daily – constipation is regarded as a scourge of a modern sedentary society, perhaps over-reliant on processed convenience food – this is borne out when we gaze upon the rows of constipation remedies and laxatives in our pharmacies and supermarkets.

Let's take a look at the effects of fiber on breast cancer recovery – what does the research say?

There is growing interest and evidence to suggest that making different food choices can help control symptoms of breast cancer treatment and improve recovery markers – avoiding food with added sugar, hydrating well and focusing primarily on plant based food. Fiber is of course beneficial for bowel health, but may also have added benefits for heart health, managing insulin resistance, preventing excess weight gain and actually helping the body to excrete excess estrogen, which is often a driver for hormonally sensitive cancers. Fiber may be Insoluble (whole grains, vegetables) or Soluble (oats, rice, beans, fruit) but both are essential and variety is best.

In their paper ‘Diets and Hormonal levels in Post menopausal women with or without Breast Cancer’ Aubertin – Leheudre et al (2011) stated that ‘…Women eating a vegetarian diet may have lower breast cancer because of improved elimination of excess estrogen’, but even prior to that, in ‘Estrogen excretion patterns and plasma levels in vegetarian and omnivorous women.’ Golden et al (1982) concluded that ‘…that vegetarian women have an increased fecal output, which leads to increased fecal excretion of estrogen and a decreased plasma concentration of estrogen.’

Fiber may also be beneficial in the management of colorectal cancer, which is on the rise in younger women and men. A recent report by the World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute for Cancer Research found that eating 90 grams of fiber-rich whole grains daily could lower colorectal cancer risk by 17 percent…and the side effects? A happier healthy digestive system, improved cardiovascular health and a lower risk of Type 2 Diabetes.

Your mother was right – eat your vegetables!

For more information on colorectal function and dysfunction, take Pelvic Floor Level 2A or for a deeper dive on the role of nutrition and pelvic health, why not take Megan Pribyl’s excellent course, Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist? Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient is also an excellent opportunity to learn about chemotherapy, radiation and pharmaceutical side effects of breast cancer treatment, as well as expected outcomes in order for the therapist to determine appropriate therapeutic parameters.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/fiber-has-surprising-anti-aging-benefits-but-most-people-dont-eat-enough-of-it/2018/04/27/c5ffd8c0-4706-11e8-827e-190efaf1f1ee_story.html?fbclid=IwAR0b-9VFUOCyUOgwe2BqV7-ahqwGzWs9rNpd1mscT75KNOGqnHm4ooFAu74&utm_term=.4d2784974ddc

Estrogen excretion patterns and plasma levels in vegetarian and omnivorous women. Goldin BR, Adlercreutz H, Gorbach SL, Warram JH, Dwyer JT, Swenson L, Woods MN. N Engl J Med. 1982 Dec 16;307(25):1542-7.

Diets and hormonal levels in postmenopausal women with or without breast cancer. Aubertin-Leheudre M1, Hämäläinen E, Adlercreutz H. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63(4):514-24. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.538487.

Perineal massage involves pelvic floor muscle stretching by application of an external pressure to muscle and connective tissue in the perineal region. It is performed 4 to 6 weeks before childbirth to help the soft tissue in that region to withstand stretching during labor. This helps to prevent perineum during birth by decreasing the need for an episiotomy or an instrument-assisted delivery. Lengthening of skeletal muscles is known to modify the viscoelastic properties of the muscle-tendon unit, which decreases the tension peak of the musculature and therefore, chances of injury.

Pelvic floor muscle stretching is performed via widening of the hiatus in the axial plane. Perineal massage is a simple technique has been found to be associated with a decrease in the incidence of perineal tears requiring suture or an episiotomy. It has also been reported to reduce postpartum pain.

Pelvic floor muscle stretching is performed via widening of the hiatus in the axial plane. Perineal massage is a simple technique has been found to be associated with a decrease in the incidence of perineal tears requiring suture or an episiotomy. It has also been reported to reduce postpartum pain.

Instrument-assisted stretching is performed with the help of an inflatable silicon balloon that can be pumped to gradually stretch the vagina and perineum. However, the evidence to support its benefit is lacking. In fact, there is some concern that pelvic floor muscle stretching may cause a decrease in muscle strength. Some have argued that such exercise neither improve or worsen pelvic function (Labrecque M, et al., Medi-dan, et al.). While a meta-analysis by Aquino, et al. concluded that perineal massage during labor significantly lowered risk of severe perineal trauma, such as third and fourth degree lacerations (Aquino, et al.).

A recent major study done by deFreitas, et al., perineal massage and instrument-assisted stretching were found to improve perineal muscle extensibility when performed in multiple sessions on primiparous women beginning at 34th week of gestation, which is very helpful in preventing child trauma in labor; however, there was no increase in muscle strength.

The technique of performing the manual perineal massage (as exemplified in the aforementioned study) may involve two sessions per week for a month by an OBGYN-focused physiotherapist. The patients are rested in dorsal decubitus position with the inferior limbs semi-flexed and the lower limbs and feet supported on the examination table. Coconut oil can be used for the perineal massage - which starts off with circular movements in the external area of the vulva, around the vagina and in the central tendon of the perineum, followed by the index and middle fingers inserted approximately 4 cm in the vaginal introitus for an internal massage of the lateral walls of the vagina ending toward the anus, repeated four times on each side, with the whole process lasting approximately 10 minutes.

Instrument-assisted procedure may include inserting the instrument (Epi-No) covered with a condom and lubricated with a water-based gel, inflated at the vaginal introitus so that 2 cm of the balloon is visible, making sure the patient can tolerate the stretching, and are advised to keep the pelvic floor relaxed as the instrument is slowly expelled during expiration. Physiotherapist supervision is necessary in order to maintain the correct positioning of the balloon as it lengthens the muscles. He/she will also ensure proper expulsion of the equipment during expiration.

Overall, perineal massage techniques (with or without instrumentation) are beneficial in terms of preventing trauma during labor. There are many studies that support the efficacy of these techniques in doing so (Leon-Larios, et al.). But it is also important to appreciate the limitations and use it judiciously.

Randomized trial of perineal massage during pregnancy: perineal symptoms three months after delivery. Labrecque M, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000.

Perineal massage during pregnancy: a prospective controlled trial. Mei-dan E, et al. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008.

Perineal massage during labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aquino CI, et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018.

Effects of perineal preparation techniques on tissue extensibility and muscle strength: a pilot study. de Freitas SS, et al. Int Urogynecol J. 2018.

Influence of a pelvic floor training programme to prevent perineal trauma: A quasi-randomised controlled trial. Leon-Larios F, et al. Midwifery. 2017.

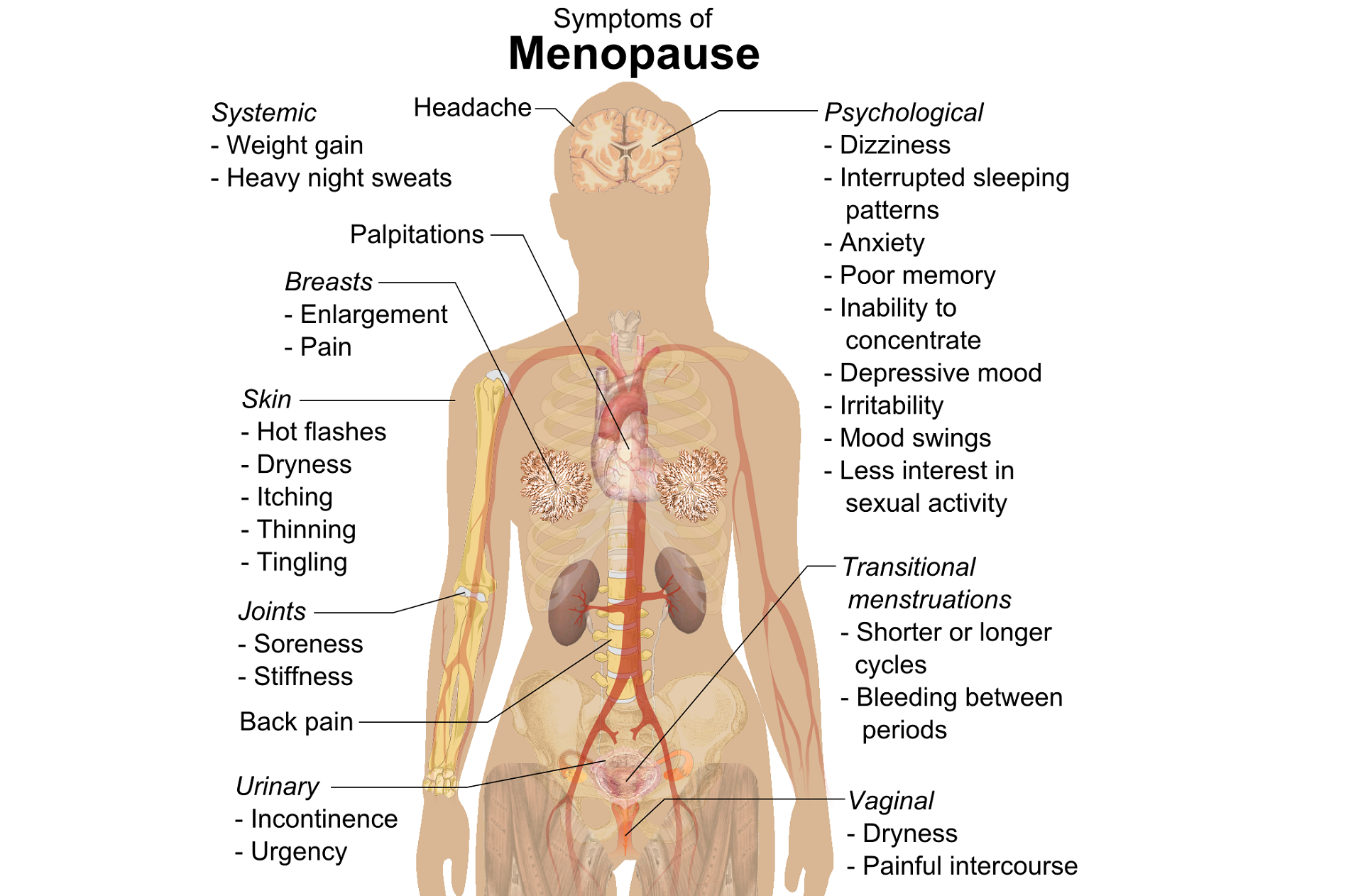

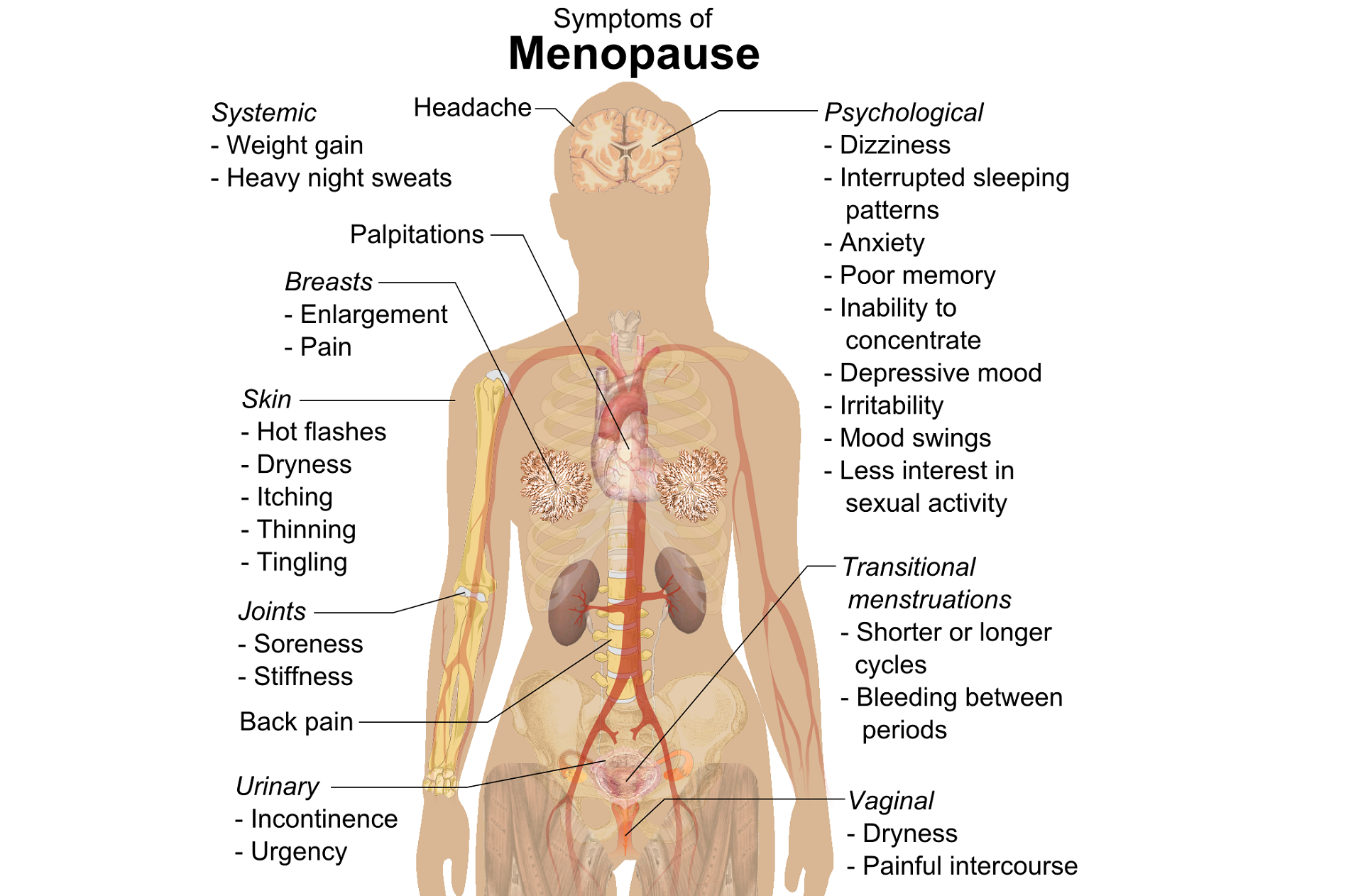

A question that often comes up in conversation around menopause is that of pelvic health – the effects on bladder, bowel or sexual health…what works, what’s safe, what’s not? Is hormone therapy better, worse or the same in terms of efficacy when compared to pelvic rehab? Do we have a role here?

An awareness of pelvic health issues that arise at menopause was explored in Oskay’s 2005 paper ‘A study on urogenital complaints of postmenopausal women aged 50 and over’ stating ‘…Urinary incontinence and sexual problems, particularly decline in sexual desire, are widespread among postmenopausal women. Frequent urinary tract infections, obesity, chronic constipation and other chronic illnesses seem to be the predictors of UI.’

Moller’s 2006 paper explored the link between LUTS (Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms) and sexual activity at midlife: the paper discussed how lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) have a profound impact on women’s physical, social, and sexual well being, and confirmed that LUTS are likely to affect sexual activity. However, they also found that conversely, sexual activity may affect the occurrence of LUTS – in their study a questionnaire was sent to 4,000 unselected women aged 40–60 years, and they found that compared to women having sexual relationship, a statistically significant 3 to 6 fold higher prevalence of LUTS was observed in women with no sexual relationship. They also found that women who ceased sexual relationship an increase in the de novo occurrence of most LUTS was observed, concluding that ‘…sexual inactivity may lead to LUTS and vice versa’.

Moller’s 2006 paper explored the link between LUTS (Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms) and sexual activity at midlife: the paper discussed how lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) have a profound impact on women’s physical, social, and sexual well being, and confirmed that LUTS are likely to affect sexual activity. However, they also found that conversely, sexual activity may affect the occurrence of LUTS – in their study a questionnaire was sent to 4,000 unselected women aged 40–60 years, and they found that compared to women having sexual relationship, a statistically significant 3 to 6 fold higher prevalence of LUTS was observed in women with no sexual relationship. They also found that women who ceased sexual relationship an increase in the de novo occurrence of most LUTS was observed, concluding that ‘…sexual inactivity may lead to LUTS and vice versa’.

So, who advises women going through menopause about issues such as sexual ergonomics, the use of lubricants or moisturisers, or provide a discussion about the benefits of local topical estrogen? As well as providing a skillset that includes orthopaedic assessment to rule out any musculo-skeletal influences that could be a driver for sexual dysfunction? That would be the pelvic rehab specialist clinician! Tosun et al asked the question ‘Do stages of menopause affect the outcomes of pelvic floor muscle training?’ and the answer in this and other papers was yes; with the research comparing pelvic rehab vs hormone therapy vs a combination approach of pelvic rehab and topical estrogen providing the best outcomes. Nygaard’s paper looked at the ‘Impact of menopausal status on the outcome of pelvic floor physiotherapy in women with urinary incontinence’ and concluded that : ‘…(both pre and postmenopausal women) benefit from motor learning strategies and adopt functional training to improve their urinary symptoms in similar ways, irrespective of hormonal status or HRT and BMI category’.

We must also factor in some of the other health concerns that pelvic health can impact at midlife for women – Brown et al asked the question ‘Urinary incontinence: does it increase risk for falls and fractures?’ They answered their question by concluding that ‘‘… urge incontinence was associated independently with an increased risk of falls and non-spine, nontraumatic fractures in older women. Urinary frequency, nocturia, and rushing to the bathroom to avoid urge incontinent episodes most likely increase the risk of falling, which then results in fractures. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of urge incontinence may decrease the risk of fracture.’

If you are interested in learning more about pelvic health, sexual function and bone health at Menopause, consider attending Menopause Rehabilitation and Symptom Management.

Sexual activity and lower urinary tract symptoms’ Møller LA1, Lose G. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006 Jan;17(1):18-21. Epub 2005 Jul 29.

A study on urogenital complaints of postmenopausal women aged 50 and over. Oskay UY1, Beji NK, Yalcin O. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005 Jan;84(1):72-8.

Do stages of menopause affect the outcomes of pelvic floor muscle training? Tosun ÖÇ1, Mutlu EK, Tosun G, Ergenoğlu AM, Yeniel AÖ, Malkoç M, Aşkar N, İtil İM. Menopause. 2015 Feb;22(2):175-84. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000278.

‘Impact of menopausal status on the outcome of pelvic floor physiotherapy in women with urinary incontinence.’ Nygaard CC1, Betschart C, Hafez AA, Lewis E, Chasiotis I, Doumouchtsis SK. Int Urogynecol J. 2013 Dec;24(12):2071-6. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2179-7. Epub 2013 Jul 17

After completing an intake on a patient and learning that her history of constipation started about 3 years ago with insidious onset, the story wasn’t really making any sense of how or why this started. Yes, she was menopausal. Yes, she seemed to be eating fiber and drinking water. Yes, she got a bowel movement urge daily, but her bowel movements felt incomplete. Yes, she was a little older, using Estrace cream, and her mobility had slowed down, but nothing seemed to make sense in the story that was leading me to believe it was an emptying problem or a stool consistency issue. She had a bowel movement urge, she could empty, but it was incomplete.

So, after explaining about physical therapy, the muscle problems involved and what we do here, it led us to the physical examination portion. I explained that we check both the vaginal and rectal pelvic floor muscle compartments to determine rectal fullness internally, check for a rectocele, check for muscle lengthening (excursion) and shortening (contraction). She was on board and desperate to find an answer. She was eager for me to help her find an answer to her emptying problem that she had for the last 3 years.

So, after explaining about physical therapy, the muscle problems involved and what we do here, it led us to the physical examination portion. I explained that we check both the vaginal and rectal pelvic floor muscle compartments to determine rectal fullness internally, check for a rectocele, check for muscle lengthening (excursion) and shortening (contraction). She was on board and desperate to find an answer. She was eager for me to help her find an answer to her emptying problem that she had for the last 3 years.

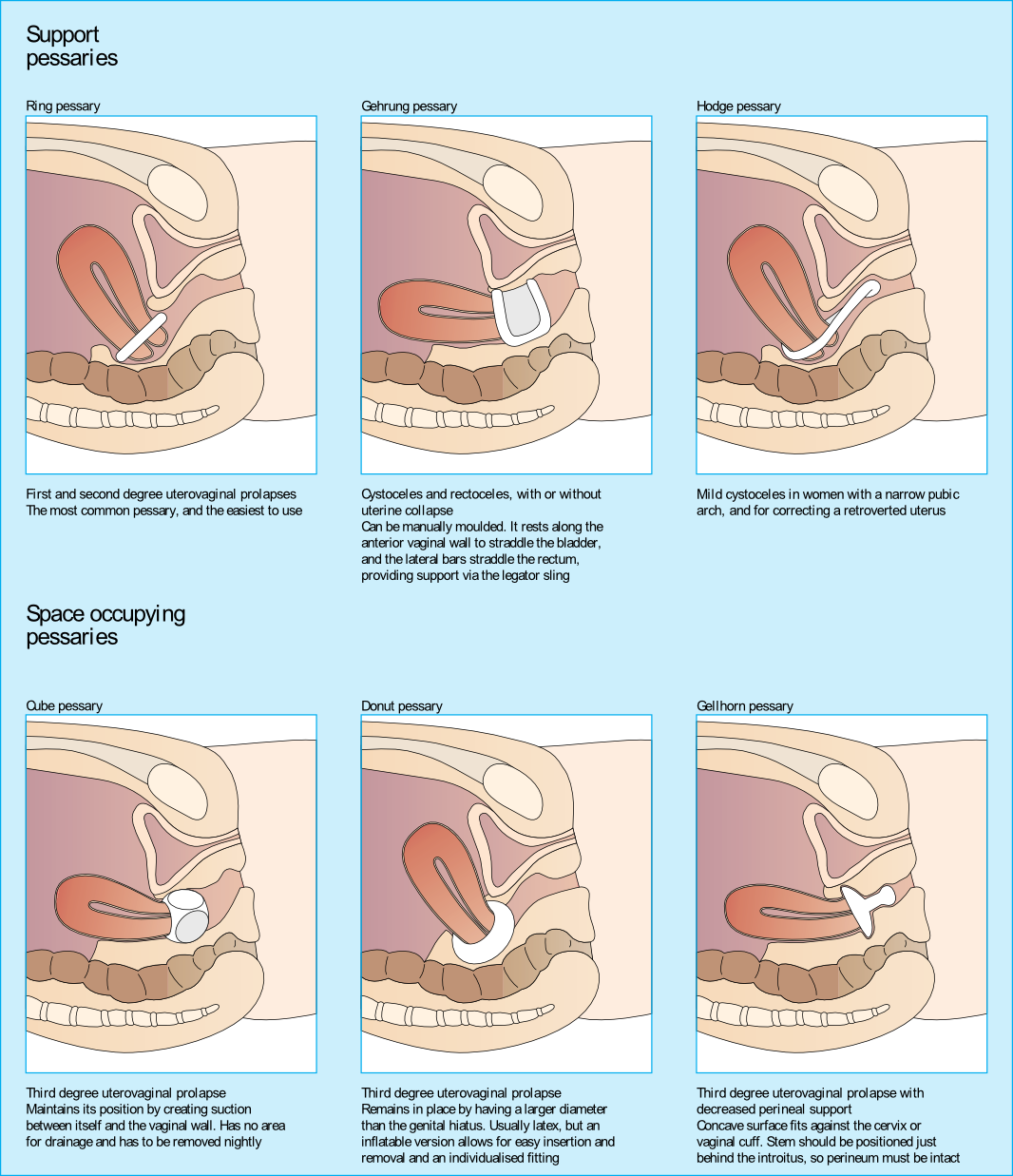

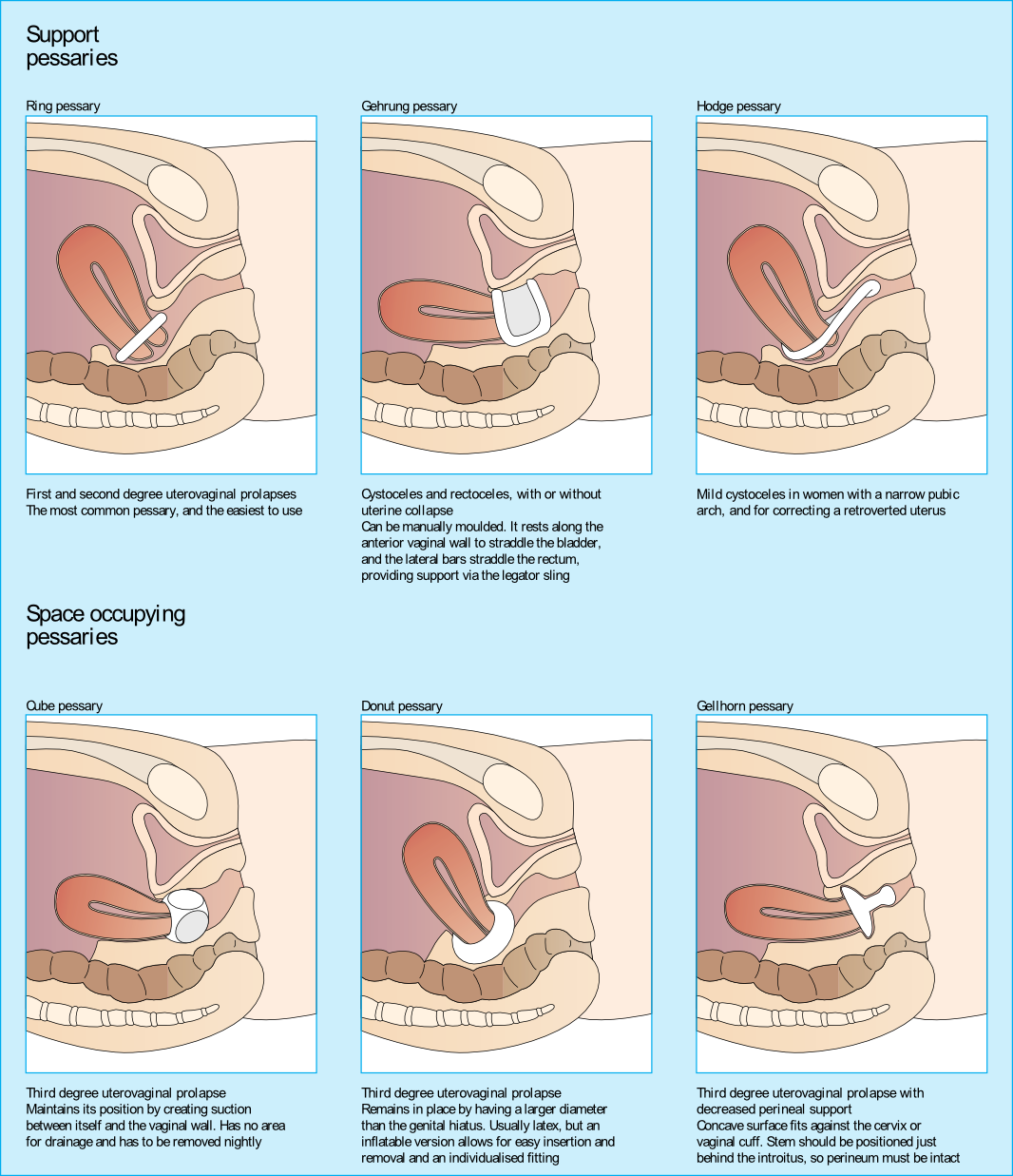

Upon entering her vaginal canal slowly, I start to move around and felt a ring of plastic. “Are you wearing a pessary?” I asked. “Pessary? Oh, yes, I forgot to tell you about that!”, she exclaimed. “How long have you been using it?” I asked. “About 3 years…” she answered.

I sent her back to the urogynecologist to get fit for another type of pessary as her muscle examination proved to be negative. Since that time, I have added the question “Do you wear a pessary?” as part of the constipation intake questions. Pessary use creates the ability for a patient to forgo or to extend their time for a surgical intervention due to pelvic organ prolapse.

Looking at the dynamics of the pessary, it may block bowel movement emptying. The recent study by Dengle, et al, published in the October 2018 in the International Urogynecological Journal confirms this anecdotal, clinical finding. The article, Defecatory Dysfunction and Other Clinical Variables Are Predictors of Pessary Discontinuation, looked at reasons for discontinuation of pessary use from April 2014 to January 2017 and did a retrospective chart review on a selected 1071 women. Incomplete defecation had the largest association with pessary discontinuation.

While there are over 20 sizes of pessaries on the market, patients will discontinue use without having a better conversation with their practitioner. From a PT perspective, when the patient comes in with bowel emptying issues, if no muscle dysfunction is found, it needs to be brought to the provider’s attention. Our role in educating the patient on the options that are available and creating this dialogue can prove to be very helpful in those suffering from pelvic organ prolapse and defecatory dysfunction.

Dengler, EG et al. "Defecatory dysfunction and other clinical variables are predictors of pessary discontinuation." Int Urogynecol J. 2018 Oct 20. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3777-1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30343377

Authors: Tamara Rial, PhD, CSPS, Kathleen Doyle-Elmer, PT, DPT and Rebecca Keller, PT, MSPT, PRPC

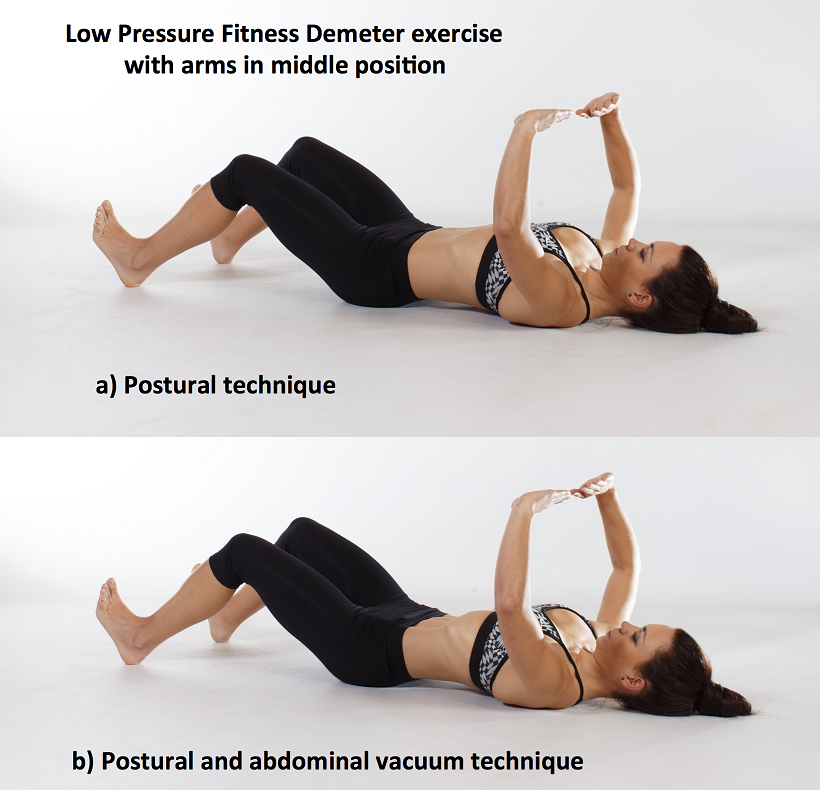

Tamara Rial, PhD, CSPS, co-founder and developer of Low Pressure Fitness will be presenting the first edition of Low Pressure Fitness and Abdominal Massage for Pelvic Floor Care Level 2 and 3 in Princeton, New Jersey in September, 2019. Rebecca Keller and Kathleen Doyle-Elmer are certified Low-Pressure Fitness specialists with training in rehabilitative ultrasound imaging. In this article, the authors discuss and explore the use of transabdominal ultrasound during Low Pressure Fitness on the abdominal and pelvic floor structures.

Real-time ultrasound imaging is a reliable and valid method to evaluate muscle structure, activity and mobility. Over the past few years, there has been increasing interest in the use of transabdominal ultrasound in the field of rehabilitation. The additional value of ultrasound imaging is that it allows for real-time analysis and visual feedback during the performance of pelvic floor and abdominal exercises (Hides et al., 1998). In the field of pelvic health, this is of notable importance when assessing proper movement of the deep abdominal and pelvic muscles during voluntary muscle actions. Transabdominal ultrasound has been found to be a safe, noninvasive, and accurate method to assess and observe muscular and fascial activity (Khorasani et al., 2012). When therapists learn how to properly use and apply ultrasound imaging, this technique can be a comprehensive tool for the clinician and a comfortable procedure for the patient. Moreover, it may be the method of choice for some patients who don’t want to have an internal pelvic examination (Van Delft, Thakar & Sultan, 2015). In this regard, a cross-sectional study found a moderate-to-strong correlation between ultrasound measurements and both digital examination and perineometry for the assessment of pelvic floor muscle actions (Volløyhaug et al., 2016).

Recently, Low Pressure Fitness has gained popularity as a pelvic floor training program aimed at reducing pressure on the pelvic structures while engaging the stabilizing muscles through postural and breathing exercises. In order to evaluate proper execution of Low-Pressure Fitness exercises as well as abdomino-pelvic muscle function during this type of training, real-time transabdominal ultrasound can be a clinically relevant tool.

Sagittal and Transverse Pelvic Floor/Urinary Bladder Assessment

The amount of movement of the bladder base on transabdominal ultrasound is considered an indicator of pelvic floor muscle mobility during pelvic floor muscle exercises (Khorasani et al., 2012). When properly executed, the Low-Pressure Fitness technique will allow the bladder to lift and the pelvic floor muscles to contract. These observed actions can be cued and progressed due to the real-time imaging biofeedback of the ultrasound. Because of the postural activation and diaphragm lift occurring during Low Pressure Fitness, the bladder fascial support system is tensioned resulting in a desirable bladder lift.

For example, we used a Pathway® Musculoskeletal Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging unit with a curvilinear transducer and Prometheus Pathway® rehabilitative ultrasound software utilizing the pre-set parameters (Abdominal Wall 7.5MHz and Bladder 5.0MHz) during a Low-Pressure Fitness basic supine posture. A standardized bladder filling protocol was used before imaging to ensure sufficient bladder filling to allow clear imaging of the base of the bladder and pelvic floor muscles.

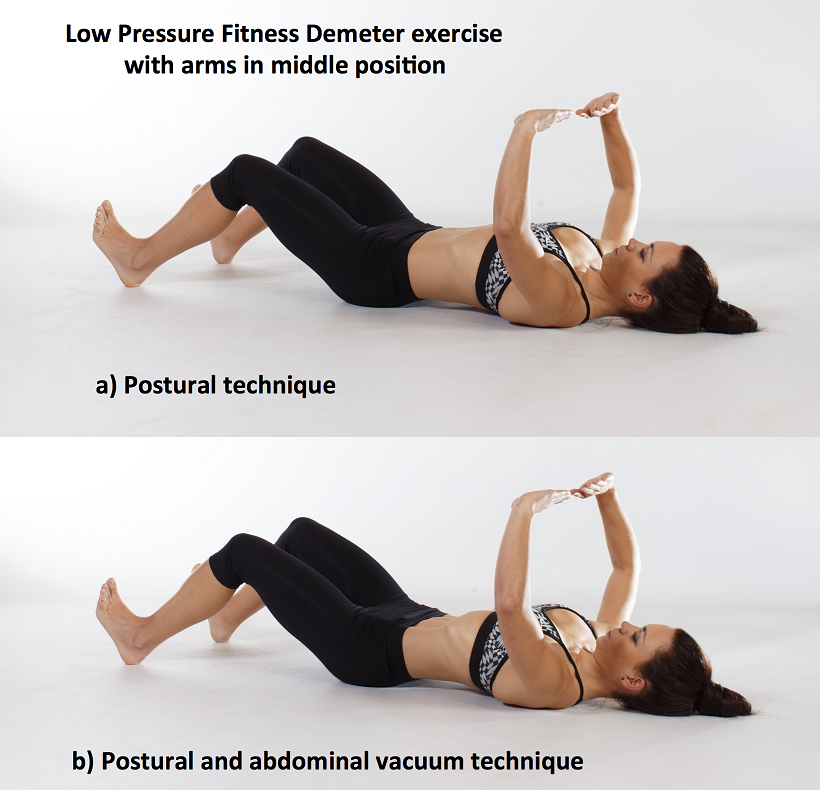

For the transverse view, radiologic standards were used, and the ultrasound transducer was placed in the transverse plane suprapubically and angled in a caudal/ posterior direction to obtain a clear image of the inferior-posterior aspect of the bladder. The participant was asked to perform the Low-Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise in the supine position with a neutral pelvis and knees flexed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Demeter exercise with postural technique and with postural and abdominal vacuum technique combined.

The following video illustrates the pelvic floor/urinary bladder during: a) resting position; b) active pelvic floor contraction; c) Low Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise and; d) Low Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise combined with a voluntary pelvic floor muscle contraction. It is noticeable a greater bladder lift and pelvic floor activation with the postural and breathing cueing added to an active pelvic floor contraction than with the pelvic floor contraction alone.

Video of the behavior of the pelvic floor muscles in a sagital and transversal view during the supine position of Low Pressure Fitness and with the combination of an active pelvic floor muscle contraction.

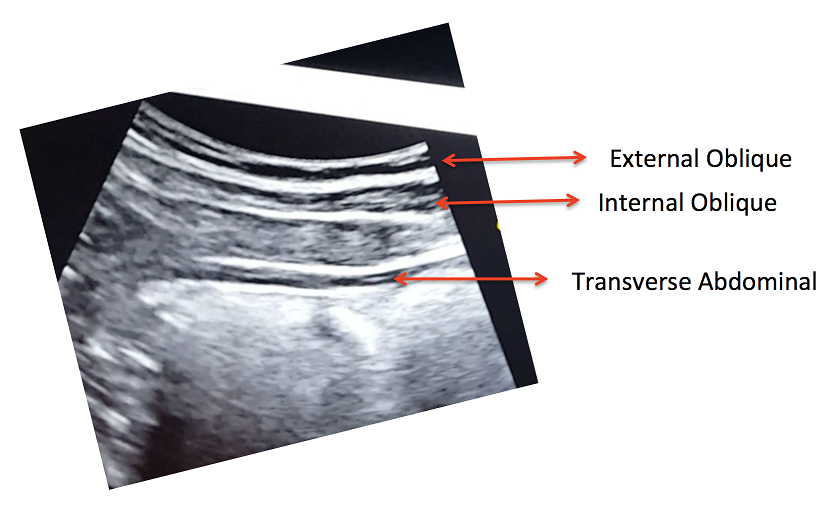

Lateral Abdominal Wall Assessment

The lateral abdominal muscle ultrasound assessment allows us to observe the structural changes produced in the transversal section of the abdominal muscles in the midpoint between the anterior iliac crest and the costal angle. At low levels of contraction, the extent of transverse abdominis thickening measured using ultrasound is reported to be a valid method of assessment compared with either fine wire electromyographic measures of transverse activity (McMeeken et al., 2004). It is well established in the scientific literature that the lateral abdominal muscles provide stability to the trunk in different functional activities. Therefore, the assessment of the size, thickness and sliding of the abdominal wall is important for patients who present with lumbo-pelvic and/or pelvic floor dysfunctions. In this regard, patients with low back pain show different abdominal wall muscle activation patterns (i.e. less slide of the abdominal fascia and muscle thickness) than those without low back pain (Gildea et al., 2014; Unsgaard-Tondel et al., 2012).

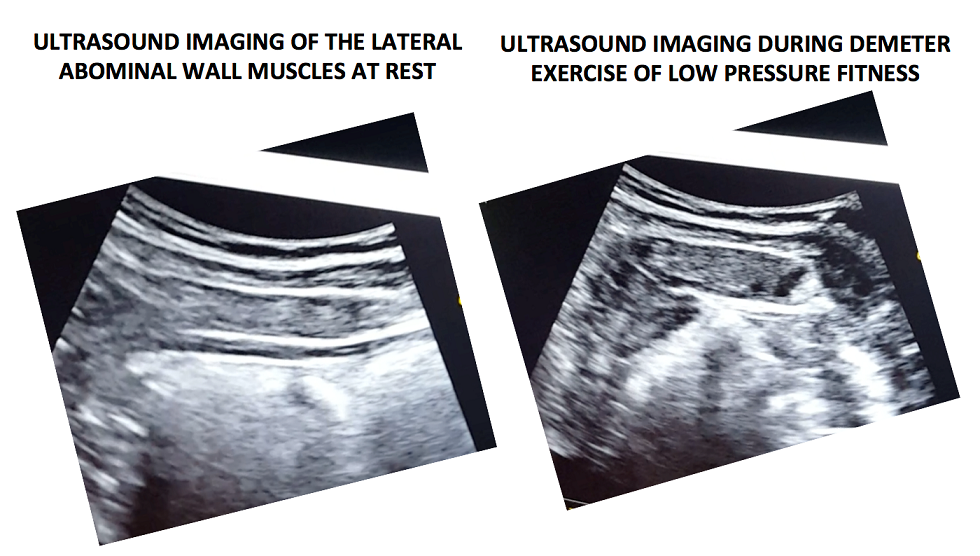

Figure 2 shows the three muscle layers of the lateral wall in the resting position. The superficial layer corresponds to the external oblique, the middle layer to the internal oblique and the deep layer to the transverse abdominal muscle.

Figure 2. View of the right lateral abdominal wall at rest.

A key breathing component of the Low-Pressure Fitness program is the abdominal vacuum which manipulates intra-abdominal, intra-thoracic and intra-pelvic pressures during the breath-holding phase. Another key aspect of Low-Pressure Fitness is the shoulder girdle activation, spine elongation and ankle-dorsiflexion (Rial & Pinsach, 2017). Of note, previous studies have demonstrated greater transverse abdominis activation when performing ankle dorsi-flexion (Chon et al., 2010). We used transabdominal ultrasound to assess the lateral abdominal wall response during ankle dorsiflexion, shoulder girdle activation and the abdominal vacuum during Low Pressure Fitness.

In the following video, a voluntary (active) abdominal contraction is performed in order to distinguish this action from the involuntary abdominal contractions during Low Pressure Fitness. Afterwards, the postural technique of ankle dorsiflexion and shoulder girdle activation are performed in the Demeter exercise with arms in middle position (Figure 1). Lastly, an abdominal vacuum maneuver is added to the postural technique. If the exercises are properly executed, the progressive sliding and thickness of the abdominal muscles throughout exercise sequence should be observable (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Ultrasound imaging at rest and during the complete LPF technique.

Video of a voluntary (active) abdominal contraction or draw-in maneuver is performed in order to distinguish this action from the involuntary abdominal contractions that occur during Low Pressure Fitness in a supine position

Muscle thickness of the transverse and internal oblique as well as a noticeable slide of the anterior abdominal fascia are observable during the Demeter exercise of Low-Pressure Fitness. This exercise pattern reflects an abdominal draw-in maneuver and a “corseting effect”. In this regard, notice the lateral pull or displacement of the edge of the anterior fascial insertion of the transverse the internal oblique muscle.

Navarro et al., (2017) used transabdominal ultrasound to assess the muscular responses of the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles in a group of women who underwent pelvic physiotherapy over two months. They found a significant increase in the transversal section of the transverse abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles when compared to resting in the supine position. Similar to the position assessed by Navarro et al. (2017), we also assessed the pelvic floor and abdominal muscle responses during a Low-Pressure Fitness supine exercise.

Transabdominal ultrasound can provide a noninvasive and informative visual biofeedback when training patients with Low Pressure Fitness. This ultrasound imaging can be a valuable tool to both the client and the clinician to objectify progress, assist with validating correct Low-Pressure Fitness form with positioning and vacuum/hypopressive maneuver as well as a motivational technique for the client. As demonstrated during our rehabilitative ultrasound imaging, observable bladder lift, pelvic floor activation and desirable lateral abdominal muscular corseting (slide and thicking) occurs during Low Pressure Fitness postural exercises and breathing. Since Low Pressure Fitness is a progressive exercise program, qualified instruction, technique driven progression and understanding pelvic floor health are needed to optimize patient outcomes.

Chon SC, Chang KY, You JS. Effect of the abdominal draw-in manoeuvre in combination with ankle dorsiflexion in strengthening the transverse abdominal muscle in healthy young adults: a preliminary, randomised, controlled study. Physiotherapy 96: 130-6, 2017.

Gildea JE, Hides JA, Hodges PW. Morphology of the abdominal muscles in ballet dancers with and without low back pain: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Sci Med Sport. 17(5): 452-6, 2014.

Khorasani B, Arab AM, Sedighi Gilani MA, Samadi V, Assadi H. Transabdominal ultrasound measurement of pelvic floor muscle mobility in men with and without chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology, 80: 673-7, 2012.

McMeeken JM, Beith ID, Newham DJ, Milligan P, Critchley DJ. The relationship between EMG and change in thickness of transversus abdominis. Clin Biomech 19: 337–342, 2004.

Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Use of real-time ultrasound imaging for feedback in rehabilitation. Man Ther. 3:125-131,1998.

Navarro B, Torres M, Arranz B, Sanchez O. Muscle response during a hypopressive exercise after pelvic floor physiotherapy: Assessment with transabdominal ultrasound. Fisioterapia 39: 187-94, 2017.

Rial T, Pinsach P. Practical Manual Low Pressure Fitness Level 1. International Hypopressive & Physical Therapy Institute, Vigo, 2017.

Unsgaard-Tøndel M, Lund Nilsen TI, Magnussen J, Vasseljen O. Is activation of transversus abdominis and obliquus internus abdominis associated with long-term changes in chronic low back pain? A prospective study with 1-year follow-up. Br J Sports Med, 46(10): 729-34, 2012.

Van Delft K, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Pelvic floor muscle contractility: digital assessment vs transperineal ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 45: 217-22, 2015. Volløyhaug I, Mørkved S, Salvesen Ø, Salvesen KÅ. Assessment of pelvic floor muscle contraction with palpation, perineometry and transperineal ultrasound: a cross-sectional study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 47: 768-73, 2016.

The following is part three in a series documenting Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT's journey treating a 72 year old patient who has been living with multiple sclerosis (MS) since age 18. Catch up with Part One and Part Two of the patient case study on the Pelvic Rehab Report. Dr. Gulbrandson is a certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist and instructor of the Meeks Method, and she helps teach The Meeks Method for Osteoporosis course.

On Maryanne’s third visit, after reviewing her home exercises I told her that today our focus was on alignment. “In dealing with osteoporosis we want the forces that act upon our bodies to line up as optimally as possible. We have gravity providing a downward force from above and we have ground reaction forces coming up from below. Remember back to your first visit when we did the Foot Press in sitting and talked about Newton’s 3rd Law? For every action there’s an opposite and equal reaction and, how by pressing your feet down it helped you to sit straighter and gave more support to your back?” She nodded in agreement.

On Maryanne’s third visit, after reviewing her home exercises I told her that today our focus was on alignment. “In dealing with osteoporosis we want the forces that act upon our bodies to line up as optimally as possible. We have gravity providing a downward force from above and we have ground reaction forces coming up from below. Remember back to your first visit when we did the Foot Press in sitting and talked about Newton’s 3rd Law? For every action there’s an opposite and equal reaction and, how by pressing your feet down it helped you to sit straighter and gave more support to your back?” She nodded in agreement.

“Well, there’s another important component to that- one that we call optimal alignment. When we sit or stand in a flexed posture, those two opposing forces do not line up well and can put undue stress and pressure on our body, particularly the vertebral bodies.” I showed her the spine again with an increased flexion (hyper-kyphosis) in the thoracic area. “It’s normal to have a kyphosis in the thoracic spine. What we don’t want is a hyper-kyphosis. We often see the apex of the increased curve around T-7, 8, 9 levels near the bra line. We also call it the “slouch line” because from the front, that’s where we slouch in sitting. A thoracic hyper-kyphosis can lead to hyper-lordosis in the lumbar spine as the body tries to counteract the flexion forces above with extension or arching in the low back. We know that Wolff’s Law states that bone in a healthy person will adapt to the loads under which it is placed.1 But we want those loads to be optimally transmitted; otherwise the adaptation can be problematic.”

With Maryanne sitting in a Perch Posture position on the side of the low mat table, I placed a 4 foot dowel rod alongside her back, touching her sacrum and apex of her thoracic curve. I instructed her to bring her occiput back toward the dowel without extending her neck. I wanted her to do more of a cervical retraction move. She was a good 3+ inches away. Previously I had measured her using the WOD (Wall to Occiput Distance).2 This helps patients understand when they are forward flexed in the upper thoracic and cervical area and becomes an exercise as well. Since Maryanne was not safe in a standing position, we used an armless chair against the wall. I turned it sideways so the side of the chair was snugged up to the wall and transferred her to the chair, sitting so that her sacrum was flush against the wall. “Bring your upper back against the wall without allowing your low back to arch forward”, I told her as I placed a folded towel behind her head. “Now you’re going to press the back of your head into the towel, just as you do when lying down in the Re-alignment routine. Before you perform the Head Press, inhale to prepare, start your exhale, then do the head press. Hold for 3 -5 seconds as you continue to exhale, then relax as you inhale. Do 3-5 reps.”

The Head Press in standing, (or in Maryanne’s case, sitting) is a convenient way to not only strengthen the back muscles isometrically, but also increase awareness of body in space and relationship of head to trunk positioning. For any individual who has developed a forward head position over a period of years, there is a loss of the proprioceptive feedback necessary to know when we’re not in alignment, even if we have the ROM to achieve it. And often a lack of strength and especially muscle endurance to maintain that optimally aligned position is problematic. Using the wall several times a day can assist in building strength and awareness. In Maryanne’s case we needed a folded towel behind her occiput to give her something to press into and prevented her from going into increased cervical extension.

“I still want you to do the Head Press in supine as part of the Re-alignment routine everyday”, I told her. “But also practice it in sitting against a wall, making sure your sacrum is right up against it. Do this several times a day for several minutes, holding 3-5 seconds each. And be sure to use your breath to maintain neutral alignment of your lumbar spine.”

And with that, our work for the day was done.

1. Wolff's Law and bone's structural adaptations to mechanical usage: an ... https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8060014

2. Concurrent Validity of Occiput-Wall Distance to Measure Kyphosis in Communities. Journal of Clinical Trials. May 18, 2012 Sawitree Wongsa1,4, Pipatana Amatachaya2,4, Jeamjit Saengsuwan3,4 and Sugalya Amatachaya1,4*